Perhaps the most moving and iconic moment in American military history is the Battle of Gettysburg. While many will commemorate the battle itself, the decision not to press this victory to complete destruction of Confederate forces was perhaps equally significant.

On July 1, 1863, advanced elements of the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia collided at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, inaugurating three days of unprecedented bloodletting that would turn back Robert E. Lee’s last invasion of the North.

The stakes were perhaps higher than at any other point in the Civil War. Northerners were so disillusioned with the conflict that one decisive Confederate victory on Pennsylvania soil could have negated U.S. Grant’s successes at Vicksburg and tipped the scales in favor of Southern slaveholding independence.

By mid-1863, the Northern states were embracing a policy of both national union and the emancipation of nearly four million enslaved people. But this whole policy clung tenuously to the fortunes of the Army of the Potomac, led by its new commander, George Gordon Meade, who was not only untested but presided over a factious army. (His portrait and a photograph of his Gettysburg headquarters are shown here.)

On July 3, in what became the battle’s final, dramatic act, Lee cobbled together a frontal assault aimed at seizing control of the key plateau on the battlefield, Cemetery Hill. The attack disintegrated in the face of determined Northern fire, the Union troops unwilling to yield crucial ground. General Meade suddenly enjoyed the crowning laurels of the first unequivocal victory of the Army of the Potomac over Lee’s vaunted veterans.

Meade, a Philadelphia patrician normally taciturn save for an occasional tantrum (earning him the nickname “snapping turtle”), wrote to his wife after the battle that “I am a great man.” Buoyed by the news of success in Pennsylvania, President Abraham Lincoln was willing to agree at first, as were some of Meade’s own cross-party subordinates.

When one officer gave Meade a back-slapping roar of approval and mentioned an open path to the White House, another stated bluntly, “Finish well this work well begun, and the position you have is better and prouder than President.” But the road to becoming a true American version of Caesar Augustus, savior of the republic from civil war, meant that Meade would have to destroy Lee’s army before it crossed the Potomac River into Virginia. And therein lay the rub.

Lee evacuated his army from the fields west of Gettysburg on the evening of July 4, beginning an arduous march where miles of wounded men, rumbling along rain-swollen dirt and gravel roads in makeshift wagons, begged to be left to die. Cavalry guarded Lee’s precious supplies as the army, in two columns, swept westward through the Cashtown and Fairfield gaps in South Mountain toward the Potomac.

Back at Gettysburg, Meade waited. That same night, July 4, he held a council of war in which his corps commanders, many of them replacements because of the awful toll of the three days’ fighting, consented to shadow Lee’s movements southwestward, using South Mountain as a shield to avoid unnecessary entanglement. The humid downpours continued until Lee reached the flooded Potomac at Williamsport, Maryland, and entrenched along commanding ground.

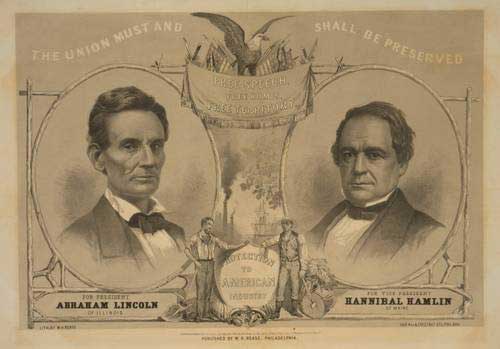

Lincoln paced anxiously, day after day and night after night, through the halls of the White House and the War Department offices across the street. Frustrated by a lack of any positive news from Meade, he sent Vice President Hannibal Hamlin (shown below) directly to Meade’s headquarters to prod him into action. According to Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s son, Hamlin carried a confidential note urging Meade to attack, and if he succeeded, the general could take all the credit himself. Hamlin arrived, but his efforts only annoyed the cautious Democratic officers of the Army of the Potomac. Meade’s own bemused son, serving on the general’s staff, opined, “what they sent him for, God only knows, [for] he does not look as if he had an idea in his old beastly head.”

But Hamlin did bring a very crucial idea, and it consumed Lincoln’s every waking hour and that of his general-in-chief, Henry Wager Halleck: Meade must attack and destroy Lee’s army before the Potomac River could be forded.

On the evening of July 12, after an afternoon thunderstorm swept the two armies into an early bivouac, Meade again assembled his corps commanders. According to Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, leader of the Twelfth Corps, Meade inquired, “Shall we, without further knowledge of the position of the enemy, make an attack?” From all but three of his subordinates Meade received the answer he expected – No, the Army of the Potomac should not attack Lee’s prepared defenses.

The next day, July 13, the Army of the Potomac waited. Some of its officers, including anti-slavery Republicans like Oliver Howard and James S. Wadsworth, wanted desperately to attack. An officer in the Third Corps, an outfit largely hostile to Meade and the conservative clique, fumed later that “The national soldiers … wished with a united voice to be led to the work of carnage.” Meade seems to have sensed the importance of the moment by the evening of July 13, and he even made some preparations for a reconnaissance-in-force. When those troops moved forward on July 14, they found only abandoned entrenchments and smoking campfires; Lee had escaped the night before.

Lincoln gave way to abject dismay and depression, sobbing into his hands when he heard the news and exclaiming to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “There is bad faith somewhere. … What does it mean, Mr. Welles? Great God, what does it mean?”

In his despondency, he actually suspected Meade and the army’s Democrats of scheming to ensure Lee’s escape across the river to safety. The suspicion was unwarranted, but the fact remained that the culture of caution so inherent in the Army of the Potomac meant that no troops would receive permission even to try.

We observe this anniversary of the most well-known Union victory of the Civil War, and one which helped turn the tide of the conflict in the North’s favor. But it is also the anniversary of one of the war’s great “might-have-beens.” Victory at Williamsport was by no means assured, but the aversion to risk meant an obvious continuation of the struggle.

One private in the Army of the Potomac, no doubt used to such experiences, simply shrugged off the failure to pursue, sighing, “Well, here goes for two years more.” Two years, yes – and hundreds of thousands of American lives.