New York Times columnist David Brooks called the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh a “nadir” in American life. And in the era of “stolen” seats on the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) and confirmations that pass by a single vote, it is easy to assume that the hyper politicization of SCOTUS nominations is a new phenomenon. On the contrary, SCOTUS nominations have been steeped in controversy since the beginning, and each controversy illustrates the political state of the era in which it occurred. While the perceived importance of Supreme Court justices has certainly expanded in the past century, fighting over those nominations has always been a part of the process.

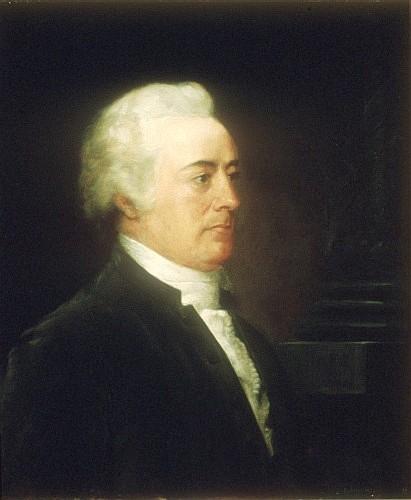

1. Justice John Rutledge (1795)

Justice John Rutledge, a vocal defender of slavery who would later be saved from drowning by two slaves.

The failed nomination of Justice John Rutledge to be Chief Justice shows just how politicized SCOTUS nominations have been. Rutledge represented South Carolina at the Constitutional Convention and Second Continental Congress where he served as a vocal defender of slavery, from which he derived a large portion of his considerable wealth. Following Chief Justice John Jay’s resignation, President George Washington appointed Rutledge Chief Justice while the Senate was in recess.

After his nomination, Rutledge loudly criticized the Jay Treaty, which was designed to ease lingering tensions with England. Unhappy with his critiques, the Senate voted against his nomination (10-14) amidst rumors of mental illness and alcohol abuse. Soon thereafter, he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Charleston Harbor but was saved from drowning by two passing slaves, providing an ironic end to the pro-slavery Justice’s time on the Court.

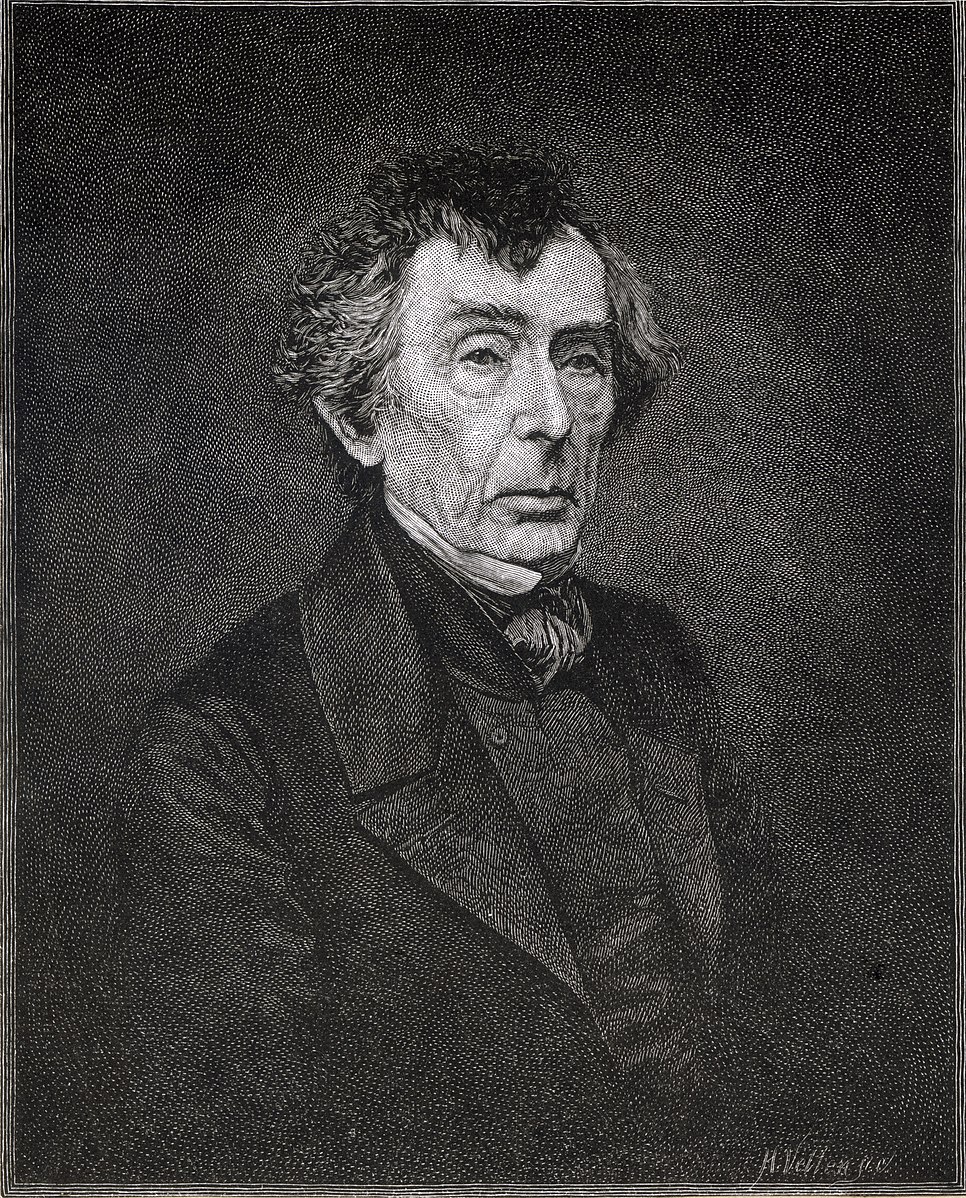

2. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (1836)

Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney, who was twice denied confirmation by a Whig-controlled Senate before finally being confirmed upon his third nomination.

Roger B. Taney’s confirmation as Chief Justice took several attempts. An extremely partisan, pro-slavery, and anti-bank Jacksonian Democrat, Taney was denied confirmation twice by a Whig controlled Senate. He became the first failed cabinet nomination when the Senate rejected President Jackson’s nomination of him as Secretary of the Treasury. And, then, the Senate rejected Taney’s nomination to an Associate Justice. When President Jackson nominated Taney again, this time to fill the late Chief Justice John Marshall’s seat, he was able at long last to overcome the strong objection of the Whigs during his third, and final, nomination hearing and was confirmed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. In that role, he wrote the controversial Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) decision, which held that neither free nor enslaved African Americans were U.S. citizens, and thus has gone down in historical ignominy.

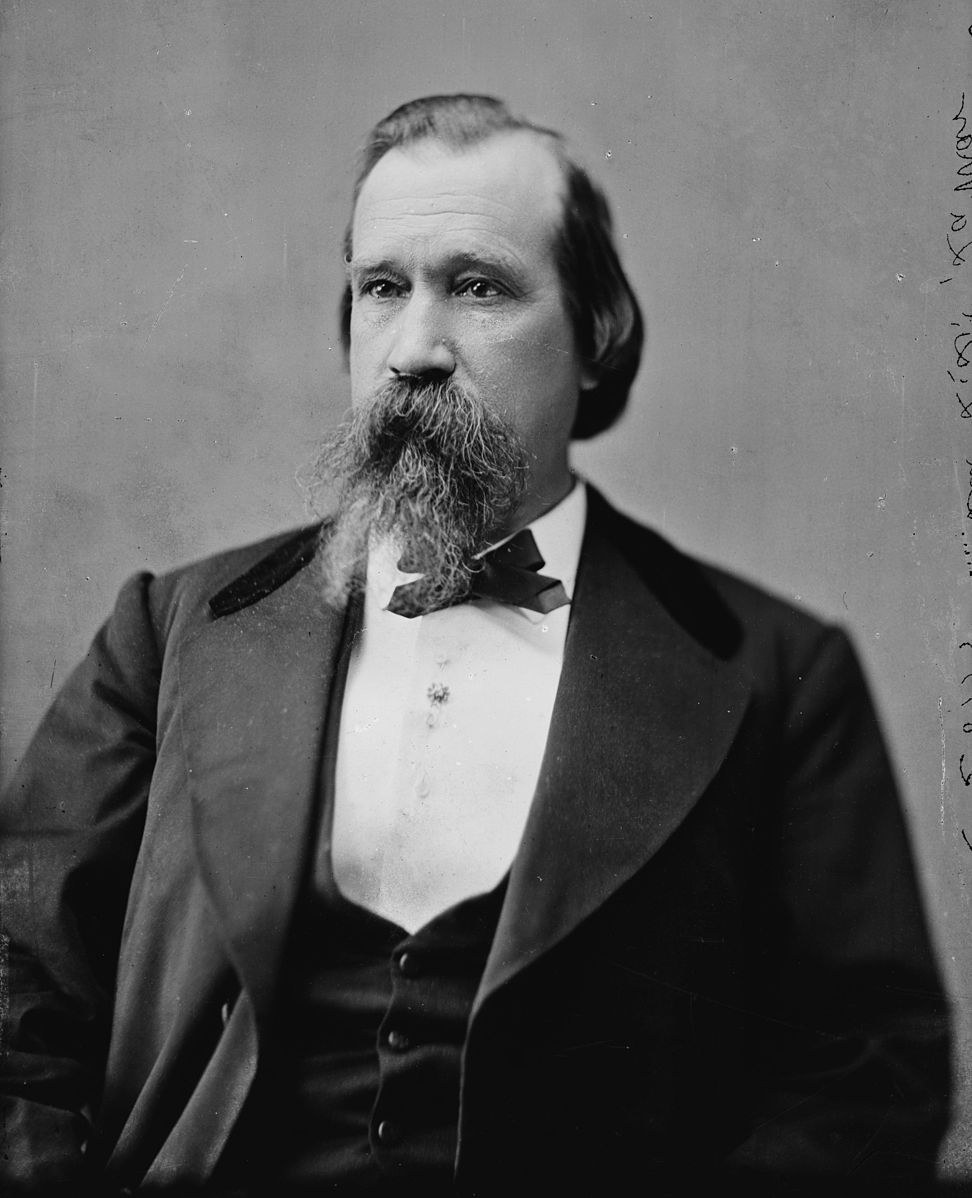

3. Justice Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II (1888)

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II, who served as a Confederate envoy to Europe before joining the Supreme Court.

In 1888, Justice Lucius Lamar was the first southerner to serve on the Supreme Court after the Civil War. Despite being an active member of the secession movement and special envoy to England and France for the Confederacy, Lamar himself believed in reconciliation and his nomination was intended to serve that purpose. Although the full Senate ultimately confirmed him, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s initial rejection and strong opposition to his nomination was illustrative of the deep regional resentments that continued well after Reconstruction.

4. Justice Louis Brandeis (1916)

“The People’s Attorney,” Justice Louis Brandeis.

Fondly referred to as “the people’s lawyer,” Justice Louis Brandeis’s progressive politics made him an interesting choice for the historically conservative SCOTUS bench. Brandeis’s commitment to monitoring the socioeconomic impact of legal decisions—including the creation of the “Brandeis Brief”—coupled with his Jewish heritage, made him an immediate target for politicians backed by Big Business. Despite the shocking outcry at his nomination by Senators, former U.S. President Taft, and several American Bar Association presidents, Brandeis insisted on attending his own hearing, which set the precedent for nominee attendance at future hearings. He was confirmed 47-22.

5. The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

A political cartoon criticizing Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attempts to gain more power for the executive branch, which included an attempt to “pack” the Supreme Court with justices favorable to his viewpoint by expanding the bench from nine to fifteen justices.

A proposed six concurrent nominations in 1937 epitomized the political nature of judicial nominations. Referred to as the Lochner Era, the conservative court of the early 20th century interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to overturn economic regulations. As a result, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal met judicial resistance. In response, Roosevelt proposed that Congress legislatively “pack” the Court by expanding the bench from nine justices to fifteen, which would have provided Roosevelt six opportunities to appoint progressives and thereby gain a favorable majority.

The Senate Judiciary Committee strongly opposed the measure, declaring it should be “so emphatically rejected that its parallel will never again be presented to the free representatives of the free people of America.” Ultimately, the Court avoided six new brethren by reversing several unpopular decisions; starting when Justice Owen Roberts made “the switch in time that saved nine” and joined the liberal justices to uphold Washington’s minimum wage regulations in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937).

6. Justice Thurgood Marshall (1967)

Thurgood Marshall (pictured with Lyndon B. Johnson) was a renowned civil rights attorney before joining the Supreme Court.

Justice Thurgood Marshall was a renowned civil rights attorney who famously argued Brown v. Board of Education (1954). A clear supporter of the Civil Rights Movement, Marshall’s nomination to both the 2nd Circuit (1961) and SCOTUS (1967) elicited criticisms that he was “too radical” and a “judicial activist.” These critiques served as thinly veiled racial disapproval of the first African American nominee to the Court.

Segregationists like Senators Strom Thurmond (R-SC) and James Eastland (D-MS) attempted to thwart confirmation. Thurmond used his hearing time to interrogate Marshall’s knowledge of obscure doctrines in an attempt to rattle him while Eastland asked if he was “prejudiced against white people in the South.” Despite this opposition, Marshall proved President Lyndon B. Johnson’s assertion that his nomination “was the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man and the right place.” He was confirmed 69-11 with 20 abstentions.

7. Robert Bork (1987)

President Ronald Reagan with his nominee to the Supreme Court, Robert Bork, who was famously rejected by the Senate for his controversial past and opinions.

The failed nomination of Robert Bork may be the most well-known on this list. Bork—who was made famous by his participation in President Richard Nixon’s Saturday Night Massacre—was a controversially conservative nominee. He opposed the rulings in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which acknowledged the familial right to privacy, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, gender equality, and the One Person, One Vote standard.

The Senate responded to President Ronald Reagan’s nomination with resounding disapproval, but Bork refused to withdraw his name, resulting in a rejection of 58-42, the largest margin by which a nominee had ever been rejected. Reagan then nominated Douglas Ginsburg, who ultimately had to withdraw when he admitted to continued marijuana use as a professor. The seat was finally filled by Justice Anthony Kennedy, whose 2018 resignation vacated the seat to which Judge Brett Kavanaugh was controversially confirmed on October 6, 2018.

8. Justice Clarence Thomas (1991)

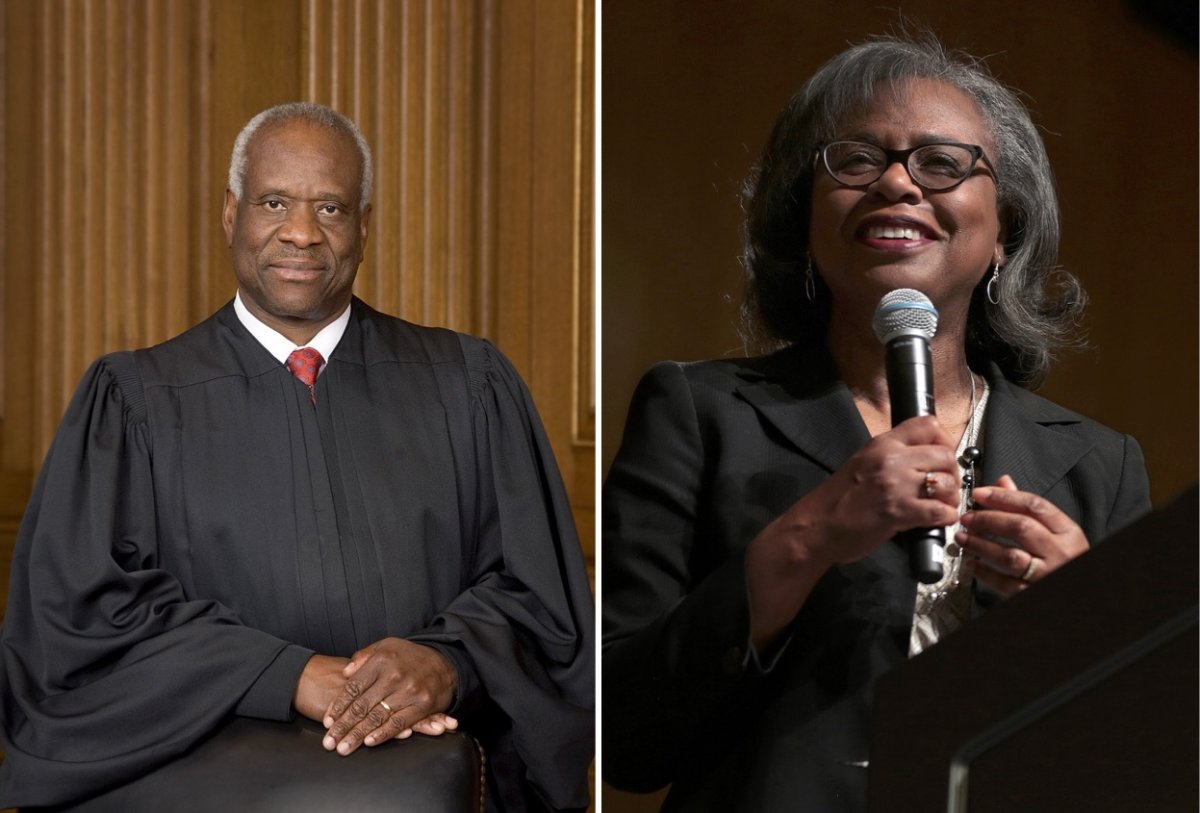

Anita Hill’s accusations of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas prefaced today’s #MeToo movement.

President George H.W. Bush nominated Justice Clarence Thomas, the second African American SCOTUS nominee, in 1991 to replace Marshall’s vacant seat. Because he had served less than two years as a federal judge, the American Bar Association did not rate him as “well-qualified.” Still, Thomas’s confirmation seemed assured until he was accused by a former employee, Professor Anita Hill, of sexual harassment while he was the Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

The Senate’s handling of the unprecedented allegations against a SCOTUS nominee, in an area of law that was less than a decade old, has been retrospectively viewed with derision. With race and gender being central issues, the hearing was tense as Hill met sexist critiques of her credibility and Thomas likened the hearing to a “high tech lynching for uppity blacks.” Thomas was confirmed, but this hearing set the stage for the handling of the allegations against Kavanaugh, including many echoing Senator Orin Hatch’s 2010 suggestion that Hill mistakenly identified her harasser.

9. Harriet Miers (2005)

President George W. Bush nominates Harriet Miers, who had never previously served as a judge or written a major journal article.

Harriet Miers was nominated to fill Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s seat in 2005. As a corporate attorney and policy staffer who had not served as a judge nor written any major journal articles, Miers’s constitutional experience and record was limited, making her a curious choice for President George W. Bush. She met immediate opposition from both parties, who considered her unqualified for the position due to her lack of a record and “incomplete” judicial questionnaire. Her withdrawn nomination suggested the breadth of the influence of the conservative legal professional association, “The Federalist Society.” The organization loudly objected to her nomination and the subsequent, confirmed, nominee was a “card carrying” Federalist Society member, Samuel Alito.

10. Judge Merrick Garland (2016)

After the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, the Republican-controlled Senate refused to hold a hearing for President Barack Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, in the middle of a contentious election cycle.

President Barack Obama’s nomination of D.C. District Court Judge Merrick Garland following the unexpected death of conservative firebrand Antonin Scalia landed in the middle of a highly contentious presidential election cycle. The Republican controlled Senate refused to hold a hearing on the nominee until after the election and Garland’s nomination ultimately expired on January 3, 2017. While controversial and the longest nomination to stall without a hearing since the Civil War, Garland’s candidacy was not the first to fail due to Senate inaction. In 1844, the Whig controlled Senate refused to call hearings on President John Tyler’s nominees to two SCOTUS seats for over a year and President James K. Polk ultimately filled them in 1845.