"Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white kids came down and saved the day."

-Julian Bond

That is an inspiring story but misleading. In recent years, historians have reinterpreted the civil rights movement, pushing its boundaries both chronologically and geographically. They have shifted the focus away from urban centers like Birmingham, Montgomery, and Atlanta, and have highlighted civil rights activism throughout the rural South. While not discrediting the work of such leaders as King, they have given due credit to lesser known individuals like Ella Baker and local activists whose names few would recognize. Perhaps most especially, they have argued for the existence of, in the words of historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, a "long civil rights movement," which began before 1955 and continued on past 1965.

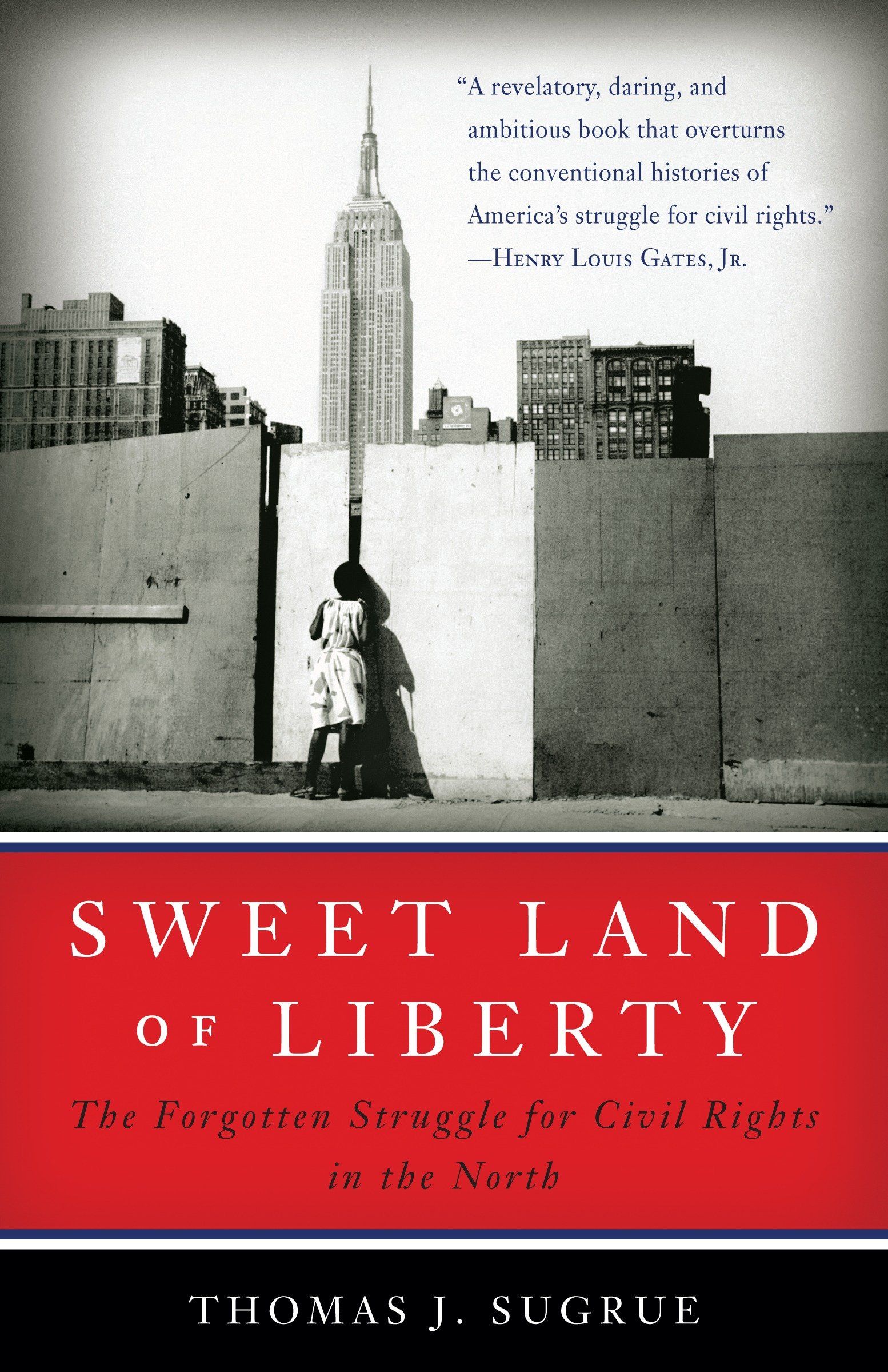

Even so, most of the literature on the "long civil rights movement" focuses on the American South, and has paid little attention to the black freedom struggle outside of the former Confederacy (with the exception of a growing literature on Black Power). University of Pennsylvania historian Thomas J. Sugrue seeks to correct this by shifting the lens of civil rights to the North in his 2008 book Sweet Land of Liberty. Sugrue is not the first historian to write on civil rights in the North. Indeed, much of the story he tells is familiar to specialists in 20th-century African American history. But while scholars such as Matthew Countryman and Martha Biondi have published important case studies on civil rights in the urban North, Sugrue offers the first study of the Northern freedom struggle across a wide geography and a long span of time.

Sweet Land of Liberty examines Northern civil rights activism from the late 19th century to the present day emphasizing the "rights revolution" (p. xvii) from the 1930s through the 1970s. Prior to the First World War, relatively few blacks lived in the urban North, but the black population burgeoned during the Great Migration of the 1910s and 1920s and grew even more dramatically during and after the Second World War.

As African Americans migrated to cities like Detroit, Philadelphia, New York, and Cleveland, they discovered that the North was not the "sweet land of liberty" they may have hoped for. Even without Jim Crow segregation codified in law, Northern cities were deeply segregated, and blacks faced widespread discrimination and inequality. In the face of such circumstances, African Americans were never passive victims. From the very beginning of black community development in the North, African Americans fought to achieve their rights, whether it was the desegregation of movie theaters in the 1920s, the judicial battle against restrictive covenants in housing deeds in the 1940s, or the fight for tenant's rights in the 1960s. The North, like the South, had a long black freedom struggle.

Sugrue argues that, while many variations of civil rights activism existed simultaneously throughout the 20th century, the overall trajectory of activism was toward increasing militancy. Some of the earliest black activists in the 1920s focused on racial uplift—that is, they believed that the black middle and upper classes ought to set an example of respectability and help the lower classes reach the same standard in order to impress whites and ultimately earn their rights. By the 1930s, with the ongoing hardships of the Great Depression, many African Americans in the North shifted their focus to working-class troubles. They viewed race and class as inseparable, and they joined with labor activists to fight for economic security, especially through unionization.

In the 1940s, the fight against fascism abroad strengthened the freedom struggle as civil rights activists adopted an international focus, linking the black American experience to anti-colonial struggles around the world. With the coming of the Cold War, McCarthyism temporarily quieted the African-American left, and the focus of civil rights shifted from economic power to integration and moral suasion against racism. Organizations like the NAACP and the Urban League fought for school desegregation, fair employment practices, and open housing.

These struggles continued into the 1960s at the same time that a growing number of African Americans adhered to the ideal of community control. Integration and community control, Sugrue points out, were never mutually exclusive, but as blacks became increasingly disillusioned by the slow pace of integration, many turned to local economic development in their own communities. As the left once again became more vocal, Black Power became the dominant trend in the North, and the freedom struggle grew more militant and revolutionary. Whereas during the 1930s, blacks had turned to the federal government as the answer to their problems, many now turned inward to their local communities. Though blacks achieved some gains by the 1970s—especially increased political representation—Sugrue argues that local communities lacked the resources to solve their own problems. With suburbanization, deindustrialization, and decreasing federal funding in the 1970s and 1980s, black communities plunged deeper into poverty.

The last three decades of the 20th century are often referred to as a "post-civil rights era," but Sugrue maintains that the struggle for civil rights did not end and, in fact, continues today. The nature of the struggle, though, fundamentally changed. Grassroots organizations, such as churches and community development programs, still lead the fight for civil rights, but these groups are no longer closely connected to one another. Sugrue argues that the freedom struggle was most effective when civil rights groups formed alliances with one another and reached across racial and class lines to work with other activists, such as labor leaders. By the late 20th century, such connections had frayed.

Sugrue's narrative travels back and forth from city to city and artfully moves from classrooms to businesses to courtrooms to neighborhoods. The major players in his story, ranging from radical to moderate and from integrationists to nationalists, often disagreed with one another about goals and tactics and even sometimes worked against each other. This is unquestionably a difficult story to tell. So what ties this sweeping narrative together? Has Sugrue identified a "long civil rights movement" in the North? I do not believe he has, nor does he intend to. Sugrue is careful to refer to "movements" in the plural, rather than to identify one grand Northern Civil Rights Movement. This is a fascinating and extremely valuable aspect of his book. He demonstrates that all of these divergent strands fit into a long Northern black freedom struggle, even if they do not constitute one, big sustained movement from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Sweet Land of Liberty, therefore, is to be praised for how it highlights the richness, complexity, and endurance of a long black freedom struggle north of the Mason-Dixon Line. It skillfully guides the reader through many twists and turns over nearly a century of civil rights history. It is a profoundly important book that reminds us that the Civil Rights struggle was a national, not simply a regional phenomenon.