The joy of reading comes in all seasons, but many people specifically like to crack open a good book in the summer. Are you going on vacation? Looking for a great Father’s Day gift? Organizing a book club? Or just looking to broaden your horizons while you stay out of the heat? I can help you. Analyzing and teaching books are large components of my job, and, honestly, I like putting together summer reading lists.

Here are ten great history books that I recommend that you read this summer. I picked books that are relatively accessible to a general audience, and they’re texts which I thought would engage readers with different interests. My work focuses on modern United States history, so all of these books have at least one foot in that field. However, I tried to pick examples on a range of topics. Some of these books surprised me when I first read them, or I have taught them and have had great conversations about them with my students.

The books are paired in order to draw out similar themes. Each set focuses on one theme or topic, but the books ask different questions about those topics. You might even consider reading them together with with a friend or a book club to compare them.

The Cold War and Its Legacies

Christian Appy is a prominent historian of the Vietnam War, and his collection of interviews with several hundred people who lived through the war shocks me with its breadth and power. The book includes the voices of American and Vietnamese people, soldiers and civilians, men and women, generals and artists, people who opposed the war and people who loved it, journalists and propagandists, and many more. The sheer labor that went into this volume will amaze you, but Appy’s most outstanding skill might be his editing. The transcript of each interview is only a few pages long, but they are grouped in a manner that invites comparisons between the participants. One section entitled “Prisoners of War,” for example, includes interviews with an American pilot shot down over North Vietnam, a Vietnamese woman imprisoned by the American-backed government in Saigon, and a war resister in the U.S. who went to prison because he opposed the draft. Even the book’s title Patriots pushes the reader to consider important questions: What does it mean to love one’s country? And what obligations do we have to one another as human beings?

While many readers will likely know a little about the Vietnam War, I suspect that few have heard of the subject of Kate Brown’s fantastic book Plutopia. During the 1940s and 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union built “atomic cities” dedicated to building their nuclear arsenals. Brown tells the history of two of these places, Richland, Washington and Ozersk in the Russian Ural Mountains. Like Appy who encourages readers to see the Vietnam War from “all sides,” Brown highlights striking parallels between the cities. The U.S. and U.S.S.R. built Richland and Ozersk in secret and limited access to them in the name of national security. Both cities polluted their environments and witnessed little-known radioactive disasters. Both cities, however, also attracted well-paid technology workers and their families, many of whom later missed the Cold War, in spite of the risks they took while living near atomic radiation. Most importantly, Brown sees the cities as keys to understanding the global legacies left to us by the arms race and the development of nuclear energy.

Christian Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides (New York: Viking, 2003)

Sexual Revolutionaries

In Bad Girls Go Everywhere, Jennifer Scanlon convincingly argues that long-time editor of Cosmopolitan magazine Helen Gurley Brown deserves credit as one of the pioneers of second-wave feminism alongside better-known figures such as Betty Friedan. She contends that Brown believed that the rules of work and courtship in this era were tilted towards men but, unlike many of her feminist peers, she thought that women were better off working within the system rather than trying to overthrow it. Brown saw her writing as a kind of advice literature designed to empower women and help them navigate a male dominated world. Scanlon does not paper over the seeming contradictions in her subject’s life. Brown, for example, often painted marriage as a dreary institution and sometimes celebrated infidelity, but she also enjoyed a seemingly happy, monogamous union with her husband of fifty-one years. Readers will enjoy learning about Brown’s complex views on work and marriage and Scanlon’s compelling interpretation of her as one of the most important figures of the twentieth century.

Written in 2015, Lillian Faderman’s epic book The Gay Revolution explains LGBT history from the witch hunts of the 1950s to the fight to legalize same-sex marriage. While acknowledging many of the challenges faced by activists over the years, Faderman’s book largely celebrates the accomplishments of the LGBT rights movement. Her book is not only very accessible, it is also comprehensive. Readers will find ample material on the homophile movement in the 1950s, Gay Liberation and the Stonewall Riots, Lesbian Feminism, the struggle against the Religious Right, the AIDS crisis, the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, the Transgender Rights movement, and many other topics. This book is ideal for someone who wants to better understand some of the recent successes of LGBT rights activists.

Lillian Faderman, Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016)

Putting Our Current Politics in Context

Johanna Schoen’s Abortion After Roe is a history of abortion rights advocates after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down most restrictions on the procedure in 1973. Schoen begins shortly after legalization when feminists opened new clinics and doctors no longer worried about being arrested. She then explains how the antiabortion movement, particularly its violent branch, drove some providers into hiding and made it more difficult for patients or doctors to speak of abortion as a social good. Schoen’s work shows that the people we call “pro-choice” sometimes differ a great deal from one another. They share an interest in keeping abortion legal and accessible, but they also have different views that reflect their positions as clinic owners, employees, doctors, patients, Washington D.C.-based policy organizations, and grassroots activists. The conflicts among these people are as interesting as the wider struggle to keep patients away from disorderly protesters and doctors safe from violence.

Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home focuses on the alarming causes that led to a militarized white power movement in the United States between the Vietnam War and the 1996 Oklahoma City bombing. To her credit, Kathleen Belew only briefly references the present, but readers who followed the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally and the recent upsurge in hate crimes in the U.S. will find this book particularly compelling background for understanding current events. Belew convincingly argues that the media, parts of the federal government, and many Americans have failed to see white power as a coherent social movement. Nevertheless, the “lone wolves” who have committed violent acts of domestic terrorism, including Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, have shared common roots in a decades-old movement committed to overthrowing the U.S. government and establishing a white homeland.

Johanna Schoen, Abortion After Roe (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

Capitalism and Its Consequences

If you like “big” histories about economics and the rise and fall of nations, you might want to read Empire of Cotton. Sven Beckert tells a sprawling history of cotton manufacturing, one of the earliest and largest pieces of the Industrial Revolution. While it might not seem like a riveting subject to some, Beckert uses the picking, weaving, and selling of cotton to explain enormous historical topics. This book ties together the rise of empires, the spread of slavery, the evolution of capitalism, the organization of labor movements, and technological innovation across the globe. Beckert shows the ways that cotton both created enormous upheaval and united people across the modern world.

While Empire of Cotton tells a global history, Bryant Simon’s The Hamlet Fire uses a smaller frame to tell an equally compelling story about capitalism. Simon’s engaging book focuses on a fire at a North Carolina chicken plant in 1991 that killed 25 people. Unlike the better-known 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, this industrial disaster produced no wider social movement for workers’ rights or legal reforms. Instead, Simon argues that the 1991 fire resulted from many Americans’ desire to make food cheap without regard for the well-being of the people who create that food. He is an incredible storyteller, and the book ties together some of the biggest themes of late twentieth century U.S. history: the growth of fast food (including Chicken McNuggets), the decline of unions, rising obesity rates, the loss of manufacturing, and the rollback of government. In spite of their different time periods, readers of The Hamlet Fire and Empire of Cotton will find striking similarities between Simon’s late twentieth century chicken processing and Beckert’s cotton pickers, factory workers, and business owners.

Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage, 2015)

The Long Black Freedom Struggle

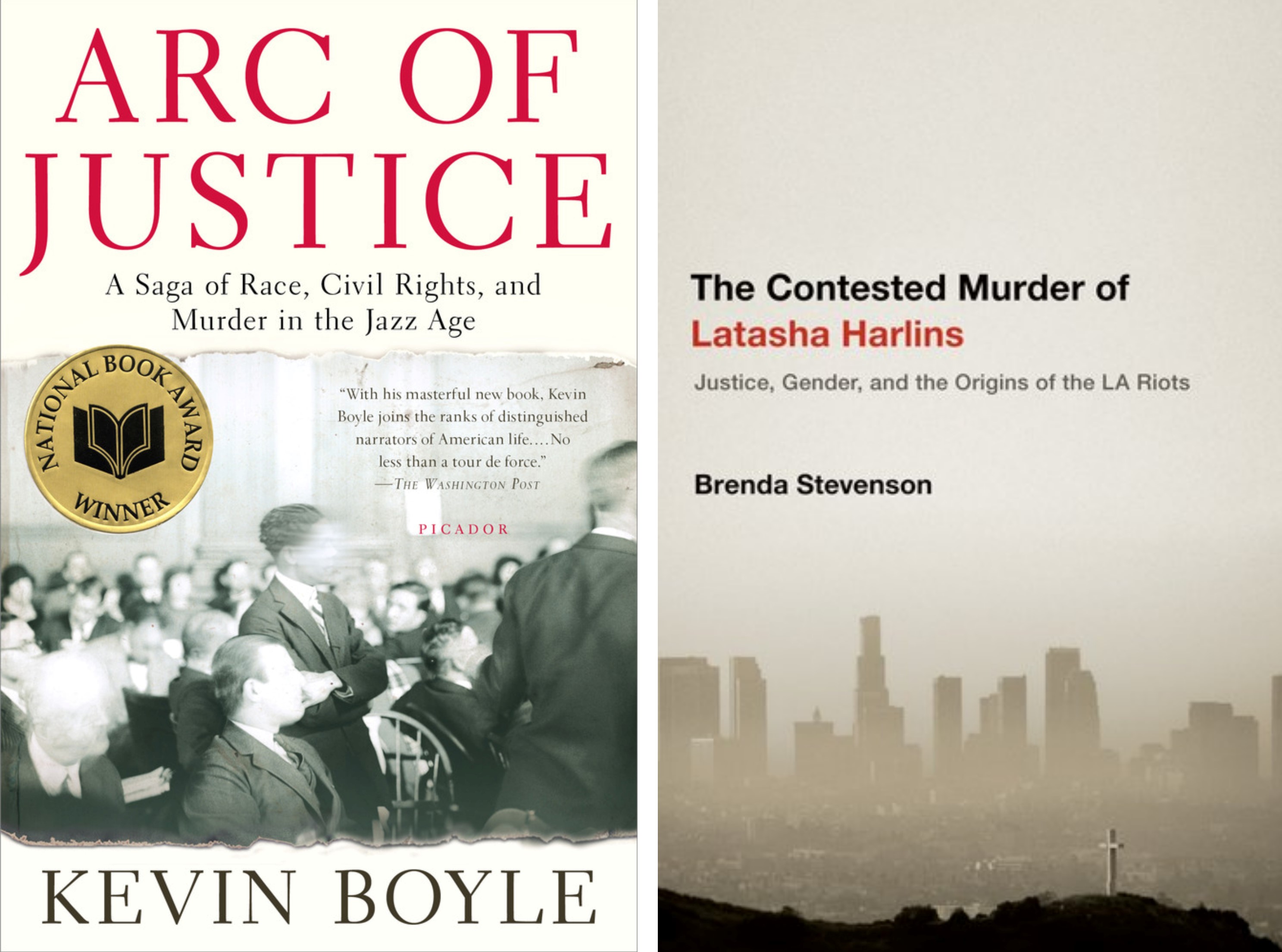

Kevin Boyle’s gripping Arc of Justice follows the murder trial of Ossian Sweet, an African American doctor who bought a house in an all-white neighborhood in 1920s Detroit. When a white mob threatened their home, Sweet, his family, and friends defended themselves with guns and killed a would-be intruder. Boyle weaves the story of the subsequent trial in with the larger history of race in America, including the Ku Klux Klan’s nearly-successful campaign for mayor in Detroit and the NAACP’s national struggle to combat segregated housing.

Brenda Stevenson similarly focuses on a murder trial to tell a larger story. In 1991, Korean storeowner Soon Ja Du shot and killed an African American teenager named Latasha Harlins in South Central Los Angeles. A jury later convicted Du of voluntary manslaughter, but the white judge, Joyce Karlin, elected to sentence her only to probation, community service, and a $500 fine. Stevenson expertly makes the three women- Harlins, Du, and Karlin- the central figures of the story, connects them to deeper trends in American history, and explains how Harlins’s killing fanned some of the outrage that later fueled the 1992 Los Angeles uprising.

These two books both focus on murder trials and use those trials to tell larger histories about race, violence, gender, and the judicial system. Readers might find interesting comparisons between the murder trials, which took place over sixty years apart. What does it mean that there are similarities between the cases? What do the trials tell us about the cities in which they took place? Why did the authors choose to write about these cases in particular?