Fifty years ago millions of Americans—young and old, urban and rural, Democrats and Republicans—participated in thousands of different events to celebrate the first Earth Day. To mark that anniversary, historian Marguerite S. Shaffer traces the origins of Earth Day, examines its impact on the environmental policies of its time, and explores its legacy on the current movement to address climate change.

Swedish teen activist Greta Thunberg catapulted into public view when she began skipping school to sit on a bench in front of the Swedish Parliament, handing out flyers that read, "I am doing this because you adults are shitting on my future."

Channeling more than a decade of warnings by prominent scientists, environmental policy makers, and a growing cadre of climate activists, Thunberg has emerged as a spokesperson for a diverse global movement to combat the climate crisis following a spate of well-publicized environmental disasters.

Demonstrators at a 2019 Italian Fridays for Future climate protest.

In fall 2019 Thunberg’s school strike evolved into a Global Climate Strike to protest government and business inaction. Organized with the help of 350.org, a grassroots organization formed by writer and environmentalist Bill McKibben, an estimated 7.6 million people turned out the week of September 20 to participate in 6,100 strikes in at least 185 countries.

The intended goal of this weeklong series of events, which was planned as a lead in to the United Nations Climate Summit, was to forge a new environmental coalition in support of phasing out fossil fuels and reducing global carbon emissions in order to avoid a set of dire consequences: rising seas, more erratic weather, stronger storms, extreme heatwaves, widespread drought, food insecurity, large scale migration, and social, political, and economic upheaval.

Greta Thunberg, 350.org, Climate Strikes, and the many other manifestations of the present climate movement are rooted in the environmental politics that emerged around the first Earth Day held 50 years ago.

A Greta Thunberg sculpture used in a September 2019 climate strike in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Although it might seem that there is little comparison between today’s climate crisis and the environmental concerns of the 1960s and 1970s, the parallels are striking. Those who would come to call themselves environmentalists in the aftermath of Earth Day were concerned about pollution, public health, fossil fuels, government action, corporate responsibility, and the future of the planet.

Like today, a series of public warnings punctuated by dramatic environmental disasters spurred people to demand action. The first Earth Day framed the questions that would drive the environmental movement: What actions can we take to protect the environment? Who is responsible? How do we ensure clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment for our children and their future?

Earth Day also sought to create a broad-based movement that could counteract business and industry and mobilize government to protect the environment and secure basic environmental rights.

People collecting litter in 1972 near Fort Smith, Arkansas.

As we confront the realities of climate change, we are living out the legacy of the first Earth Day. We are asking the same questions, marching the same streets, and looking to the systems set in place to address our current environmental crisis. Thinking about the history of Earth Day provides perspective on both the achievements and the limitations of the modern environmental movement.

Educating Americans about the Environment

In June 1969, Stephanie Mills stood before her graduating class at Mills College in Oakland, California, and told her fellow classmates and their families that the promise of the postwar American Dream was a “cruel hoax.” She went on to shock her audience when she pledged never to have children. “I have asked myself what kind of world my children would grow up in.”

“Because, you see,” she lamented, “if the population continues to grow, the facilities to accommodate that population must grow, too. Thus we have more highways and fewer trees, more electricity and fewer undammed rivers, more cities and less clean air. Mankind has spread across the face of the earth like a great unthinking cancer.”

The “Mood of Campus Valedictory Speakers is Somber” article in The New York Times, June 1969.

Her words hit a national nerve. Under the headline “Mood of Campus Valedictory Speakers is Somber,” the New York Times singled out Mills’s speech as “perhaps the most anguished statement” of her graduating cohort. Her lament for America’s future provides a compelling lens on the issues and impact of that first Earth Day in April 1970.

As the 1960s progressed, environmental and ecological issues captured national attention. Scientists and policy makers began to sound the alarm about unbridled natural resource development, pesticides and toxic chemicals, overpopulation, nuclear fallout, the excesses of corporate expansion, and an economic system addicted to unlimited growth.

These warnings were amplified by a number of well-publicized environmental disasters. By the time Mills took the podium in the summer of 1969, Americans had grown increasingly concerned about an environmental crisis looming over the nation’s future.

After more than a decade of prosperity and expansion, made manifest in suburbs and shopping malls, automobiles and interstate highways, and an unending array of consumer gadgets, public attention had begun to shift. Some started to question the destructive tendencies of postwar affluence.

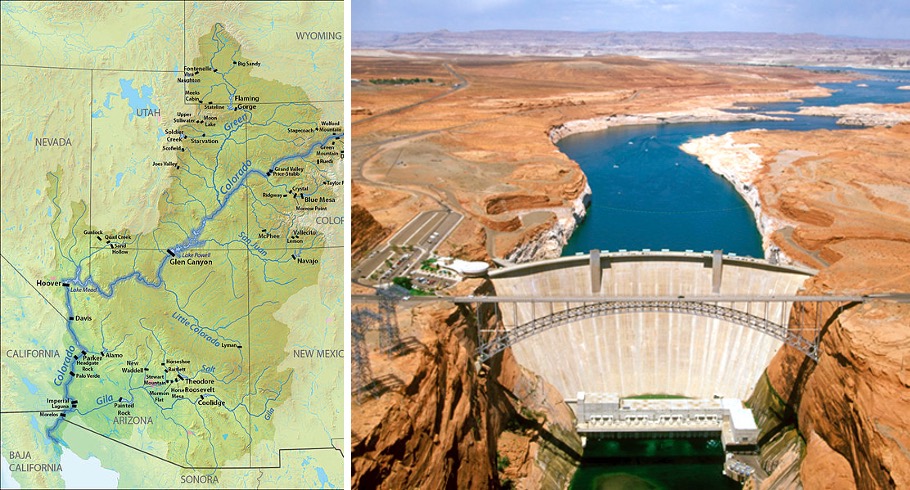

A 2013 map of dams on the Colorado River (left). An aerial view of Glen Canyon Dam in 2019 (right).

In the late 1950s, the Sierra Club, led by executive director David Brower, revitalized the wilderness conservation movement with the fight to save Dinosaur National Monument from being inundated by a dam on the Green River in Echo Park, Colorado. The subsequent flooding of Glen Canyon in 1963 and the ensuing fight, three years later, against a U.S. Bureau of Reclamation proposal to build two dams that would flood the Grand Canyon, sparked public outrage among a growing coalition of wilderness advocates.

In fact, the Sierra Club coffee table book The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon in the Colorado, with photographs by noted nature photographer Elliot Porter, compelled Mills to “make common cause with the planet.”

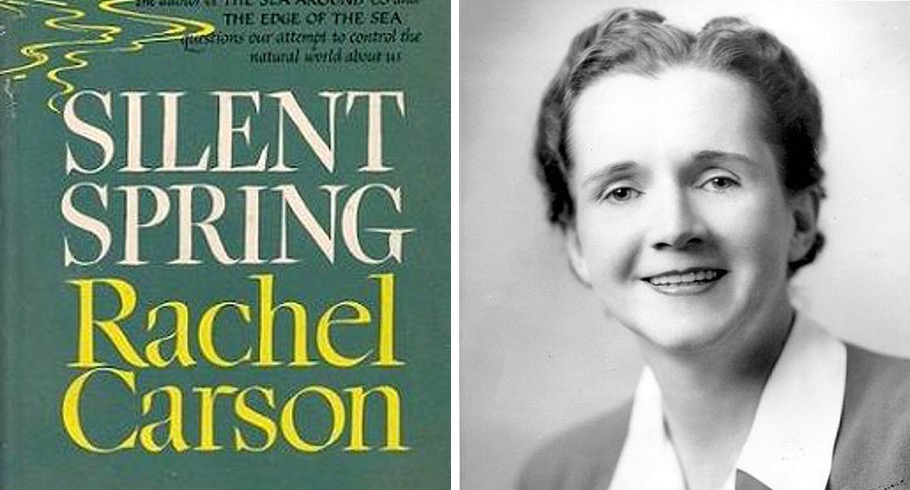

While Brower helped popularize a growing interest in wilderness conservation grounded in outdoor recreation, Rachel Carson’s 1962 bestseller, Silent Spring, shifted the focus from distant wilderness to the ecological systems in our own backyards.

Silent Spring, published in September of 1962, became an immediate bestseller and helped lead to a federal ban on the pesticide DDT (left). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee Rachel Carson in 1940 (right).

Carson, a marine biologist who worked for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, challenged the chemical industry’s widespread use of synthetic pesticides in agriculture and pest management. Silent Spring documented the little-known impact of chemicals such as DDT on living organisms. In eloquent prose, Carson described the intricate web of relationships—the food chains linking plants, bugs, birds, fish, animals, and humans—connecting all life forms, and she warned against upsetting the balance of nature.

“Our heedless and destructive acts enter into the vast cycles of the earth and in time return to bring hazard to ourselves,” she explained in her testimony to a Senate subcommittee on pesticides. Silent Spring taught Americans to understand the world in ecological terms, and in the process laid the groundwork for looking at the interconnections between human beings and the natural world through an environmental lens.

Silent Spring was followed by a number of publications (both scientific and popular) that chronicled the ill effects of postwar consumer abundance.

Books such as The Quiet Crisis (1963) by Stuart Udall, Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed (1965), Donald Carr’s Death of Sweet Waters (1966), Barry Commoner’s Science and Survival (1967), William Paddock and Paul Paddock’s Famine 1975! America’s Decision (1967), and Garrett Hardin’s seminal essay “Tragedy of the Commons,” (1968) warned about pollution, corporate self-interest, nuclear fallout, famine, and the inevitable overuse of natural resources by self-interested individuals.

The Population Bomb (1968), co-written by Paul and Anne Ehrlich, provided the most dramatic bookend to Carson’s earlier best seller. It was the Ehrlichs’ book that compelled Mills to issue her pledge to forgo having children.

While these books cataloged a range of pressing environmental issues, a series of environmental disasters dramatized the realities of an environment in crisis. On June 22, 1969, the Cuyahoga River, which ran through the industrial heart of Cleveland and drained into Lake Erie, made national news when it spontaneously caught fire.

The fire was the most dramatic in a series of pollution problems that had degraded the Lake Erie watershed. Detroit and Buffalo pumped raw sewage into the lake. Washing machines drained synthetic detergents that made mounds of soapsuds a common sight along the shoreline. Algal blooms killed fish, resulting in “no swim zones” across local beaches. “Anyone who falls into the Cuyahoga does not drown. He decays," went a common Cleveland joke. Time Magazine dubbed Lake Erie “a North American Dead Sea.”

In 1955, soap suds measuring 15-feet high covered a vehicle bridge in Valley View, Ohio.

In September of 1969, NBC aired “Who Killed Lake Erie?”, a documentary produced by Fred Freed that the New York Times described as “a panoramic view of the once lovely lake now clogged with billions of gallons of industrial waste … more billions of raw sewage from cities bordering the lake, foaming detergents, and pesticides, litter, garbage, dead fish, and surrounded by filthy beaches and recreation areas.” By the end of 1969, over a million people had signed a petition in support of the “Save Lake Erie Campaign.”

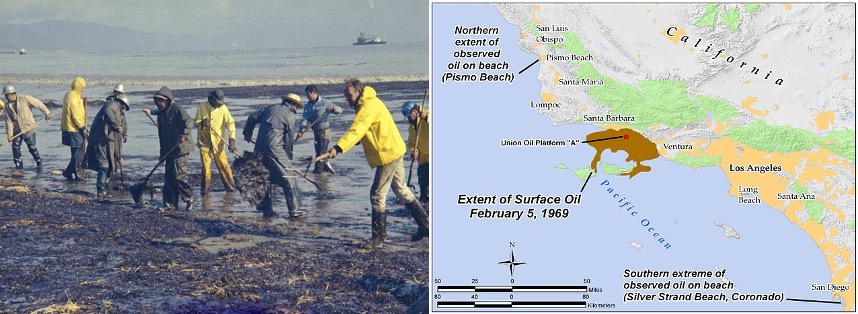

However, the made-for-TV environmental catastrophe that most traumatized the American public unfolded along the scenic beaches of an upscale resort town in Southern California.

On January 28, 1969, a Union Oil well burst off the coast of Santa Barbara and over the ensuing weeks 235,000 gallons of crude oil blackened 30 miles of idyllic Pacific coast shoreline. As the disaster unfolded, millions of Americans tuned in to scenes of thick black sludge lapping up onto the sand, suffocating oil-covered birds, starving baby sea lions, and helpless weeping spectators.

Santa Barbara, the epitome of an idyllic postwar paradise, became the poster child for the indiscriminate ravages of pollution, an imperiled environment, and a future at risk.

Workmen in 1969 using rakes, shovels, and pitchforks to clean up oil-soaked straw from the Santa Barbara Harbor beach (left). A map that illustrates the extent of the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill (right).

These images of the environmental carnage juxtaposed with another major news story that summer—the Apollo moon walk and photos of a glowing blue Earth floating in space—brought home the message that all Americans, and all of Earth’s inhabitants, were potential victims of an escalating environmental crisis.

Earth Day as a Culmination

In August of 1969, Gaylord Nelson, the Democratic senator from Wisconsin, who had made a name for himself on Capitol Hill fighting for conservation issues, traveled to the Santa Barbara coast to see the impact of the spill first hand. On the flight home, inspired by the grassroots tactics of the student-led antiwar movement, he was struck with the idea of organizing a national teach-in to raise awareness about environmental issues.

A month later in a speech to the Washington Environmental Council in Seattle, he announced his plan. “I am convinced that the same concern the youth of this nation took in changing the nation’s priorities on the war in Vietnam and on civil rights can be shown for the problems in the environment,” he told his audience. “That is why I plan to see to it that a national teach-in is held.”

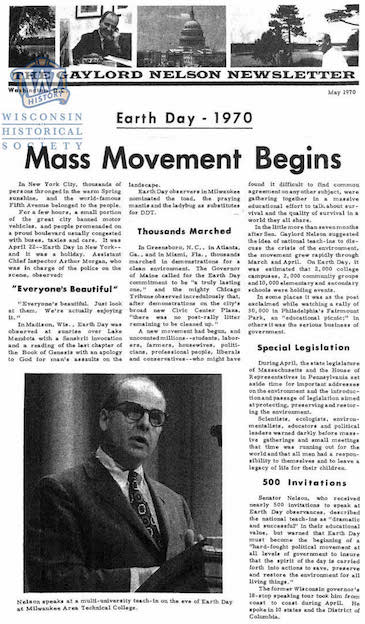

Senator Gaylord Nelson’s May 1970 newsletter describing Earth Day events.

Senator Nelson quickly set about laying the foundations. Working with his staff, he appointed a steering committee, set up a non-profit organization, launched a publicity campaign, and started fund-raising. That fall, Time, Newsweek and the New York Times ran stories about the planned nationwide teach-in. The National Education Association publicized the event through their state newsletters.

With offices in a run-down building near Dupont Circle, the national office had three mandates: to spur the organization of local events, to craft and distribute information, and to provide logistical assistance. A small group of young idealists—graduate students, political activists, and journalists among them—guided tens of thousands of people at colleges and schools across America.

The success of the first Earth Day rested in its organizational structure and implementation. Rather than top-down management, Earth Day emerged from the bottom up with minimal guidance at the national level. Individuals from communities across the country were encouraged to plan their own events, enacting what would become a popular Earth Day slogan: think globally, act locally.

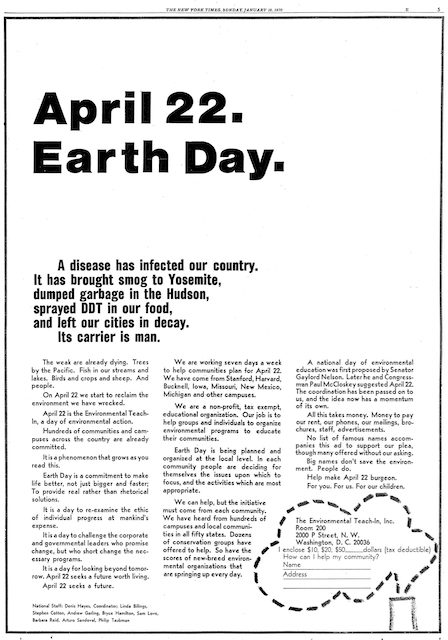

On January 18, 1970, a full-page ad in the New York Times publicly announced the name and date of the event in bold font and capital letters: APRIL 22. EARTH DAY.

The 1970 advertisement placed in The New York Times by Senator Nelson’s non-profit organization, The Environmental Teach-In. (Image courtesy of Earth Day Network.)

“A disease has infected our country,” the copy explained. “It has brought smog to Yosemite, dumped garbage in the Hudson, sprayed DDT in our food, and left our cities in decay. Its carrier is man.” The text that followed declared, “On April 22 we start to reclaim the environment we have wrecked.”

Explaining the idea of the environmental teach-in, the copy continued, “Earth Day is a commitment to make life better, not just bigger and faster, to provide real rather than rhetorical solutions. It is a day to re-examine the ethic of individual progress at mankind’s expense. It is a day to challenge the corporate and governmental leaders who promise change, but who shortchange the necessary programs. It is a day for looking beyond tomorrow. April 22 seeks a future worth living.”

Earth Day organizers also sought to link the event to other social issues of the day—racism, poverty, and war.

“Ecology,” explained Environmental Action coordinator Denis Hayes, “is concerned with the total system—not just the way it disposes of its garbage.” The movement was not simply about litter prevention or even pollution control. “Our goal is not to clean the air while leaving slums and ghettos, nor is it to provide a healthy world for racial oppression and war.”

The national organizers sought to build a consensus that would allow for celebration as well as critique; to unite New Left radicals, middle-class suburbanites, working class union members, the urban poor, educated professionals, wilderness advocates, and countercultural dropouts in a new environmental coalition.

This public call to action catalyzed the largest demonstration in American history to date.

On April 22, 1970, over 20 million people turned out on college campuses, in high school gymnasiums, at community centers, and in public parks to participate in over 12,000 individual local events. Fifteen hundred colleges staged Earth Day teach-ins.

Congress members took the day off to support activities organized by their constituents. Over 35,000 speakers—including Stephanie Mills—lectured about environmental issues. Sesame Street (PDF File) and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood devoted shows to the environment and the three major commercial networks provided Earth Day programming.

After noon on April 22, 1970, only people were allowed on New York City’s Fifth Avenue.

Earth Day events ran the gamut from celebration to protest and targeted an array of environmental issues: pollution, litter, overconsumption, the fossil fuel industry, automobile culture, green space, outdoor recreation, natural resource conservation, and ecology.

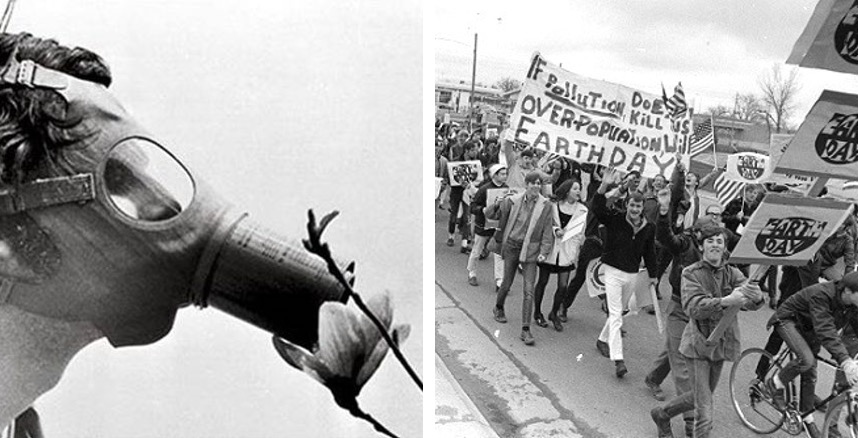

Although many college and school programs were not covered in the press, the national news media documented civic activities across the country. Organizers in New York City closed Fifth Avenue and 14th Street to all vehicular traffic—no cars, no trucks, no cabs, no buses. Over 250,000 people paraded and picnicked in the streets. Fourteenth Street was lined with exhibits and street art: a mannequin in a gas mask, bottles of Hudson River water labeled “unsafe to drink,” a 200-foot long bubble identified as “Pollution Free Atmosphere.”

In Boston, antipollution protesters at Logan Airport staged a mock funeral with signs reading “death by biocide,” resulting in 15 arrests. In Camden, Delaware, Governor Russell W. Peterson helped community members clean up litter. In Washington, DC, participants at a rally at the Interior Department spilled oil on the sidewalk in protest against pollution caused by off-shore oil drilling. In Chicago, a “garbage eating dragon” accompanied marchers on their way to Civic Center Plaza.

An event organized by a group called Black Survival in St. Louis engaged in street theater to draw attention to distinct inner-city problems such as lead poisoning, rat and roach infestations, insufficient municipal services, and the health impact of higher rates of air pollution.

Wearing a vintage gas mask, Peter Hallerman poses during a 1970 Earth Day demonstration (left). (Image courtesy of www.smithsonianmag.com.) Denver high school students walk or bike to school on April 22, 1970 (right).

At Tulane University in New Orleans, students tagged Louisiana's oil industry with the "polluter of the month" award. Presciently, Dr. J. Murray Mitchell, a government scientist, told an Earth Day crowd: “pollution and over pollution, unless checked, could so warm the Earth in 200 years as to create a greenhouse effect, melting the arctic ice cap and flooding vast areas of the world.”

Earth Day had widespread popular appeal. One journalist likened Earth Day to Mother’s Day, noting that “no man in public office could be against it.”

But not everyone joined in and some expressed skepticism.

Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes, one of the nation’s first Black mayors, questioned the prioritization of air and water pollution over the more basic needs of Cleveland’s poorest citizens. Richard G. Hatcher, mayor of Gary, Indiana, went a step further, asserting that the “concern with environment has done what [the segregationist governor of Alabama] George Wallace was unable to do: distract the nation from the human problems of the black and brown America, living in as much misery as ever.”

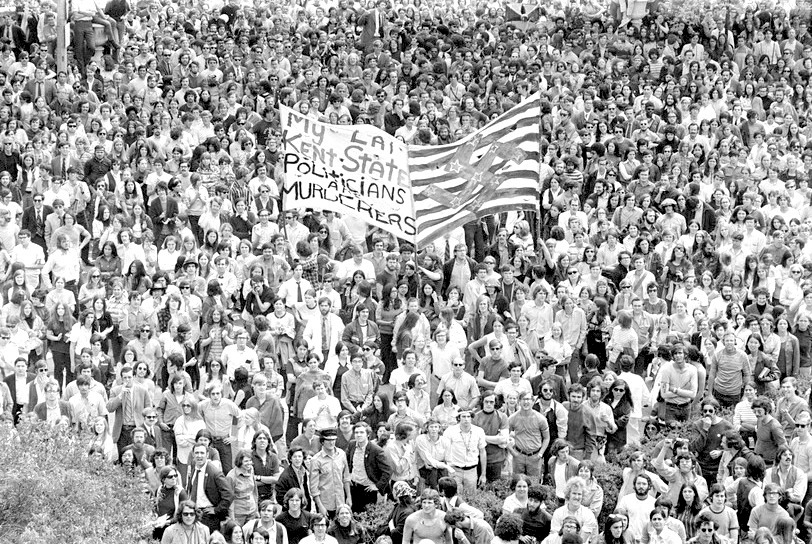

Antiwar protesters at the Massachusetts State House on May 5, 1970.

Similarly, antiwar protesters complained that concern about litter and pollution diverted public attention from the much more pressing atrocities of the Vietnam War. Critics on the left sought to dismiss environmental concerns as the complaints of a privileged white middle class, sheltered from the systemic inequities of race and class dividing America.

There were also critics on the right. Spurred on by the conservative John Birch Society, some questioned the coincidence that Earth Day occurred on the 100th birthday of Russian revolutionary and founder of Soviet communism Vladimir Lenin. One Georgia politician sent telegrams to officials across the state warning that Earth Day might be a Soviet plot.

Despite these criticisms, Earth Day united diverse constituencies to forge an environmental consensus. Youth activists, suburban housewives, union members, businessmen, scientists, conservationists, Democrats and Republicans participated. Some communities planted trees or picked up trash; some listened to lectures or public debates; still others marched in demonstrations or engaged in carnivalesque street theater.

In all, Earth Day popularized an environmental ethic grounded in the ideal that every American had a right to clear air, clear water, and a toxin-free environment.

Earth Day as a Beginning

While Earth Day did not initiate modern-day environmental policy, it did establish a presence for environmentalism in Washington, making it a bipartisan political cause.

The Kennedy and Johnson administrations had already introduced legislation that made the environmental quality of the nation’s air and water a federal responsibility. In the lead-up to Earth Day, President Richard Nixon pushed this further, setting the pillars of the modern-day environmental regulatory state in place.

In his State of the Union speech, Nixon called for Americans to make “peace with nature” and provide reparations “for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water.” He went on to proclaim: “Restoring nature to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions. It has become a common cause of all the people of this country.”

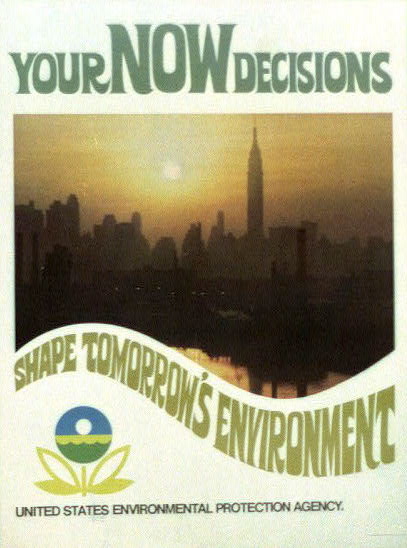

A 1972 Environmental Protection Agency poster.

On January 1, 1970, Nixon signed the landmark National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the backbone of modern environmental policy. Under this legislation all federal agencies were required to evaluate the environmental impact of their actions. After Earth Day, Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), a new federal agency designed to be the engine of the emerging environmental regulatory system.

A cascade of bipartisan legislation, regulating pollution and protecting the environment, followed. Between 1970 and 1975, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the Water Pollution Control Act, the Federal Insecticide, Rodenticide, and Fungicide Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Coastal Zone Management Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Energy Supply and Environmental Coordination Act, the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act, the Energy Policy and Conservation Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and a federal ban on DDT.

Issues of air and water pollution, pesticide use, biodiversity, habitat protection, and fuel economy were now matters of national policy with the goal of safe-guarding the nation’s environment.

Although Earth Day did not spark a radical movement for social and structural transformation, it did propel significant action that helped to frame the issues and actions of modern-day environmentalism. Building on widespread public interest, membership in environmental organizations increased and new environmental groups formed. In 1970, Environmental Action, the League of Conservation Voters, and Friends of the Earth became actively involved in electoral politics.

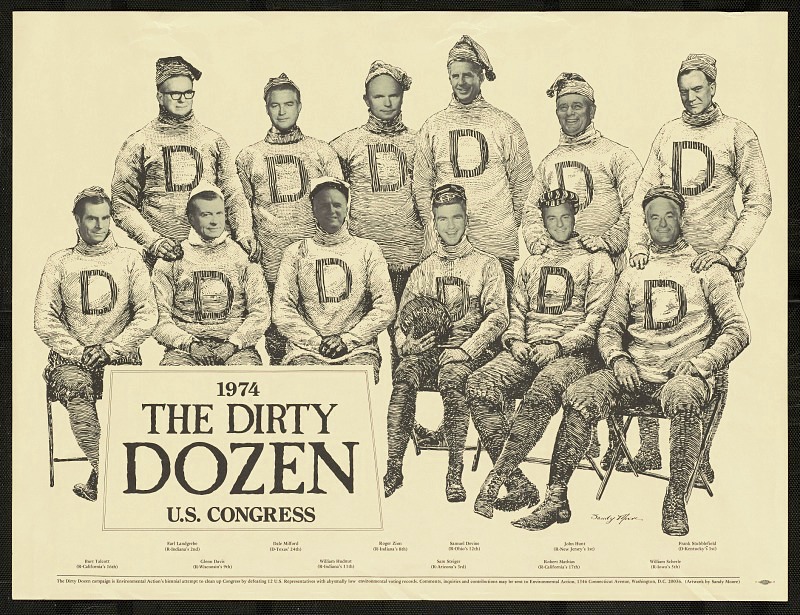

A 1974 Environmental Action poster that depicts 12 congressmen who voted against environmental concerns. Their faces are superimposed on a picture of an early twentieth-century “sports team.” (Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.)

Friends of the Earth assembled voting records on environmental issues collected by the League of Conservation Voters in combination with overviews of major environmental issues to publish The Voter’s Guide to Environmental Politics in October 1970.

To demonstrate the power of the post-Earth Day environmental coalition, Environmental Action assembled a list of 12 congressional incumbents, labeled “the Dirty Dozen,” who were targeted for defeat in the November elections: seven of the 12 lost. In addition, environmental lobbyists became a new fixture in Washington, sitting at the same political table as business and industry.

News media began regular environmental coverage and publishers developed environmentally focused book lists. Earth Day also further popularized environmental education and sparked interest in newly emerging environmental studies programs across the country.

Californians recycling household items in 1996.

At the local level, communities established ecology centers and environmental organizations that organized tree planting, trash cleanup, and organic gardening, and coordinated recycling programs. Across the spectrum, Earth Day helped set in place principles and practices in support of clean air, clean water, and a system of managed natural resources.

A Legacy with Limitations

As the Trump administration systematically dismantles the federal environmental regulatory state and snubs the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, as climate deniers gain public traction questioning the science of global warming, as the fossil fuel industry masks ramped-up extraction with “green washing” about its commitment to renewable energy, the challenges facing the modern environmental movement are all too apparent.

Despite growing support for environmental protection as evidenced by recent Pew Research polls, and increased participation in environmental activism as evidenced by the growing Climate Movement, the environmental regulatory system set in place after Earth Day is ineffectual in the face of our current environmental crisis for four key reasons.

First, by focusing on local activities and education, and embracing the strategy of thinking globally and acting locally, Earth Day established a framework that unfairly equated individual citizens and multinational corporations, suggesting that they each had equal responsibility and power to solve environmental problems. The modern environmental movement has had difficulty contesting the structures of corporate power that constrain the choices and actions of everyday citizens.

A 12-foot-long shark sculpture made in 2015 from plastic debris collected on beaches.

Second, the environmental regulatory state that took shape after the first Earth Day was grounded in the political framework of the modern democratic nation state, which by design shoehorns ecological systems into political boundaries. This federal regulatory system worked to address local and regional pollution problems within the United States.

However, climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and sea level rise, do not respect national boundaries. Further, multinational corporations have found ways to circumvent federal regulations. As environmental problems transcend national borders and expand to planetary scale, the federal environmental regulatory regime is ill-equipped to take action.

Third, Earth Day environmentalism fell victim to the limitations of a political system dominated by special interests. In building the infrastructure for a new environmental politics and securing environmental advocates a seat at the table along with business, industry, and a host of other interest groups, environmentalism became just one more special interest vying for attention amidst an array of other pressing policy issues.

The Dakota Access Oil Pipeline being installed between North Dakota farms in 2017.

In this political battle ground, environmental issues were pitted against economic interests, and the long-term goals of environmental protection often lost to the short-term focus on private profit.

Finally, an unspoken premise of the first Earth Day was grounded in the idea that widespread understanding of basic environmental science would lead to good environmental policy. Greta Thunberg’s demand that political leaders read the science on climate change and take action reflects that core belief.

However, the politics of polarization has politicized science. Objective scientific analysis grounded in fact-based data has been tainted by political ideology, which has called into question the core principles of modern environmentalism.

As a result, the critical questions of the environmental movement raised on the first Earth Day remain.

Ohio teenagers earn a $1,000 grant in 2019 to create an environmental sustainability project at their high school. (Image courtesy of Piper Sullivan.)

Who is responsible for safeguarding the environment: individual citizens, local communities, national governments, NGOs, multinational corporations? How do we balance ecological systems and economic systems? How do we promote environmental justice? What is the best way to protect the ecological systems that support all life on Earth? How do we ensure a sustainable future for our children and grandchildren and beyond?

Read more from Origins on the Environment: Amazon Rainforest under Threat; The Re-Polluting of America; The West without Water; Fluoride; Vaccination; A Century of HIV; Australia and the World Water Crisis; The River Jordan; Who Owns the Nile?; The Changing Arctic; Over-Fishing in American Waters; Climate Change and Human Population; and the Global Food Crisis.

Listen to more on Environmental history: Climate Change and Human Life; The Sixth Extinction and Our Unraveling World; HIV/AIDS: Past, Present and Future; Food for Thought: Diet in History; and The Greening of China?

Watch more: Climate Change.

Carr, Donald Eaton. Death of the Sweet Waters. Norton, 1966.

Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

Christofferson, Bill. The Man from Clear Lake: Earth Day Founder Senator Gaylord Nelson. University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Commoner, Barry. Science and Survival. Viking, 1967.

Bell, Garrett de. The Environmental Handbook: Prepared for the First National Environmental Teach-in. Ballantine Books, 1970.

Bell, Garrett de.The Voter's Guide to Environmental Politics before, during, and after the Election. Ballantine Books, 1970.

Dunaway, Finis. Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images. The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Ehrlich, Paul R. The Population Bomb. Ballantine Books, 1968.

Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement, Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. http://www.nelsonearthday.net/index.php Accessed March 16, 2020.

Gottlieb, Robert. Forcing the Spring : The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement. Rev. and updated ed. Island Press, 2005.

Mitchell, John G. Ecotactics: The Sierra Club Handbook for Environment Activists. Pocket Books, 1970.

Nader, Ralph. Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile. Grossman, 1965.

Nelson, Gaylord. America’s Last Chance. Country Beautiful Corporation, 1969.

Nelson, Gaylord, et al. Beyond Earth Day: Fulfilling the Promise. University of Wisconsin Press, 2002.

Paddock, William, and Paul Paddock. Famine, 1975! America’s Decision: Who Will Survive? Little, Brown, 1967.

Rome, Adam. "'Give Earth a Chance': The Environmental Movement and the Sixties," Journal of American History 90 (September 2003): 525-554.

Rome, Adam. The Genius of Earth Day : How a 1970 Teach-in Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation. Hill and Wang, 2013.

Rothman, Hal K. The Greening of a Nation? : Environmentalism in the United States since 1945. Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998.

Steinberg, Theodore. Down to Earth : Nature’s Role in American History. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Stone, Robert. Earth Days: The Seeds of a Revolution. Arlington: PBS, 2010.

Udall, Stewart L. The Quiet Crisis. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.