The U.S. National Park Service, the federal agency charged with overseeing the more than 400 parks that make up our national park system, was created on August 25, 1916. The national parks, which include an astonishing range of natural areas as well as historic and other cultural sites, are often touted, justifiably, as world-class travel destinations. But they are far more than simply places to vacation in. John Reynolds, a respected park manager who had a career with the Park Service of more than forty years, has eloquently described their deeper meaning:

One way to look at the national park system is as an unparalleled intellectual feast, solidified by the fact that the parks themselves are real places where you can pair the intellect with emotion and place. You can follow our common fight for independence and creating and keeping a nation. You can think through our struggles to perfect who and what we are and who gets to share the American Dream. You can traverse ecological biomes from the Virgin Islands to the Arctic, from Fire Island to the islands of the Pacific. You can savor some of our creative juices in art, poetry, sculpture…. And much, much more. Our parks are our history, our environment, our culture, our fights and our future.

When you “pair the intellect with emotion and place,” what often results is a moment of insight: an unexpected instance where you suddenly understand something deeper about history, about nature, about others, about yourself. Here I offer ten “Moments of Insight” that I have had in the parks over the years. The name of this feature is “Top Ten Origins,” but the list below should be understood as a representative sample of the kinds of introspective experiences the parks offer, rather than as a ranking of the best—something that really is impossible, since all of us bring different sets of values and expectations to our national park experiences.

1. An American Serengeti:

Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming/Idaho/Montana

Bison and pronghorn in Lamar Valley, Yellowstone National Park. (National Park Service/Diane Renkin)

Just outside the main tourist loop in our oldest national park lies the closest thing we have to the Serengeti—that sprawling grassland ecosystem in Tanzania and Kenya that is home to the world’s greatest spectacle of massive migratory herds of animals. I was in Yellowstone the third week of June this year, during what will probably go down as the busiest summer in the park’s history. Traffic on the loop road was heavy. But when we turned off at Tower–Roosevelt and headed to the Lamar Valley, it was like entering a completely different park. The traffic drops off and the landscape opens up, with expansive vistas on every side. Once in the valley, the Lamar River wanders along low benches backed by forested slopes and snow-covered mountains in the distance. And, the day we were there, along the river were bison—hundreds of them. You can see them in many places in Yellowstone, but not often in herds like this. Lamar is also good for seeing other grazers such as pronghorns and elk. Here, too, is probably the best place in the park to try to glimpse wolves, the species that, in our version of the Serengeti, plays the same ecological role as lions and cheetahs do in the real one.

2. “Death Wears Bunny Slippers”:

Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, South Dakota

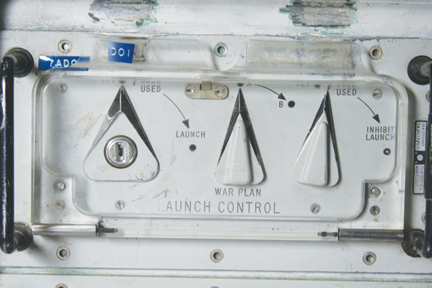

Commander’s key insert to launch missile, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site. (National Park Service)

One of the most sobering experiences I have ever had came when I stood before the firing console in the Minuteman nuclear missile underground control center that is preserved at this recently designated historic site. There before me was a simple key mechanism that, had the proper codes been received by the missileer, would be activated to launch warheads capable of reaching Moscow in less than a half-hour. Even more chilling was the realization that the missileers—understandably—behaved like regular human beings once locked into the control capsule for a 24-hour shift. Off came the official jumpsuits and on went sweats, shorts, even sleepwear—whatever was comfortable. The idea that Armageddon could be unleashed by someone in pajamas was the source behind the satirical Air Force patch that reads “Death wears bunny slippers”—with a picture of the Grim Reaper at the console launching a missile while wearing fuzzy pink bunny slippers. The park does an excellent job of conveying how boredom and banality were (and still are) part of the challenge of the nuclear missile crew’s mission, arguably the most important in all the military.

3. Voyage to the Bottom of the (Ancient) Sea:

Badlands National Park, South Dakota

Various sedimentary rock strata are visible in many areas of Badlands National Park.

Just a few miles down the road from Minuteman Missile, the panoramas of Badlands National Park carry a signature of time far deeper than the recent Cold War history interpreted at the historic site. Badlands’ geologic formations strike some people as otherworldly, but many of us find them mesmerizing. Most of the time, they also look desiccated—signifying a place that doesn’t get a lot of water in any form. But it wasn’t always so. At the base of the park’s exposed rock formations lies what is called the Pierre Shale, a belt of black rock that was once mud on the floor of a shallow inland sea that existed some 70 million years ago. When you stand at the one of the park’s overlooks today, you are actually looking down into an ancient marine environment.

4. Voyage to the Top of the (Rising) Sea:

Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida

Fort Jefferson in the distance, Dry Tortugas National Park. (© 2010 GEDApix—used by permission)

Where sea meets land is one of the most dynamic areas on the surface of the earth: ask anyone who has spent time on a barrier island how much one big storm can change things. Today, climate change is poised to profoundly transform many coastal areas, and in fact is already causing sea levels to rise. Historic Fort Jefferson, which sits on low-lying Garden Key in Dry Tortugas National Park, is Exhibit A of the kind of difficult decisions the National Park Service will have to make about what to do with coastal structures threatened by sea-level rise. One of the country’s largest 19th-century masonry fortifications, Fort Jefferson is exceptionally vulnerable to rising seas and increasingly intense storm damage. Although the agency is fighting to preserve it, it may become one of the first really significant historic sites that the Park Service is forced to concede to the ravages of climate change.

5. The Empty House:

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, North Carolina/Tennessee

The Steve Woody House, Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Far from the usual tourist drives, the three parallel valleys of Cataloochee are tucked into the southeastern corner of the park in North Carolina. Once home to a deep-rooted Smokies community, the residents were forced out when the national park was created in the 1920s and 1930s. Much of the charm of Cataloochee today comes from the historic homes, farm buildings and fields, churches, and cemeteries the Park Service has preserved to provide a suggestion of what life was like for the mountain folk. Particularly haunting is the Steve Woody place, a sturdy white clapboard house that lies by itself about a mile’s hike beyond the end of the road in Big Cataloochee. You can walk right in (the front door has been removed), linger in the silent rooms, and, perhaps, ponder the logic of emptying a house in order to interpret the lives that once flourished in it.

6. The Genius of Kirkkonummi:

Gateway Arch National Park (Redesignated in 2018), Missouri

Gateway Arch National Park (National Park Service)

It could hardly have been predicted that the man who would one day create one of America’s most recognizable landmarks would come from a small Finnish town called Kirkkonummi. But that is where Eero Saarinen, the man who designed the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, was born in 1910. His father, Eliel, was himself an influential architect. The family moved to the United States in 1923, and Eero studied architecture at Yale. In February 1948 Saarinen’s design for the Gateway Arch was unanimously voted the winner of a three-year design competition for a structure that would serve as centerpiece of the new Jefferson National Expansion Memorial.* The jury recognized the genius of the (seeming) simplicity of his design: a catenary arch, the same shape as that made by a chain hanging by its own weight when supported at the ends. Technically, Saarinen’s stainless-steel arch is an inverted weighted catenary: inverted, because the arch points upwards, and weighted so that it is thicker at the base than at the top. Brilliant mathematics is the ultimate source of the splendor of this futuristic, yet enduring, monument.

7. Art that Got Left Behind:

Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark District, Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve. (National Park Service)

Far inside what is otherwise the wilderness of our largest national park, Wrangell–St. Elias in southeastern Alaska, lies a wholly unexpected treasure: the remains of the historic copper mining town of Kennecott. Active only for a little more than 25 years, this complex produced over $200 million worth of ore and served as the foundation for the namesake mining company that still operates elsewhere today. For the miners at Kennecott, the climate and isolation were harsh, the pay low, and the work dangerous and exhausting. Still, the small community thrived so long as the copper held out. Today, the National Park Service administers the site as a national historic landmark district. A few of the structures are being stabilized and restored, but many are dilapidated. What is perhaps most impressive about the place is the sculptural quality of the bright red buildings, almost tumbling down the mountainside, which have the flavor of monumental environmental art about them, suggesting something along the lines of the famous (to some, infamous) installations of the Christo/Jeanne-Claude collaboration. There is a raw beauty to Kennecott that makes it resonate with the spectacular natural landscape in which it sits, made all the more affecting by the fact that it was unintentional.

8. The Long View:

Marsh–Billings–Rockefeller National Historical Park, Vermont

Fall colors in the forest of Marsh–Billings–Rockefeller National Historical Park. (Nora Mitchell, used by permission)

This relatively new park, which preserves one of the nation’s most attractive and intriguing managed landscapes, tells a story of enlightenment: how successive conservationist-owners (George Perkins Marsh, Frederick Billings, and the Rockefeller family) took a degraded, cutover landscape and returned it to ecological health and attractiveness. It is easy to be captivated by the impressive setting of the main mansion (and its furnishings and artwork), but the real genius of the place is in its combination of natural forests and managed plantations, some of which date back more than a century, interspersed with fields and wetlands. Huge native field maples grow near red pine plantations, and sustainable harvesting of timber takes place alongside rigorous ecological monitoring. You leave having learned that, with enough patience and persistence, even the most devastated landscape can be recovered.

9. Drunk on Words:

Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, North Carolina

The study, Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site.

Sandburg’s reputation has rebounded recently after years of neglect as more readers have come to re-appreciate his strengths as a celebrant of American democracy in verse, song, and biography. At the center of the national historic site is Connemara, Sandburg’s house, where one can linger on the broad front porch and look across a fetching pasture to the Blue Ridge in the distance beyond. The house is fascinating and completely without pretension, as evidenced in the simple furnishings of the poet’s study upstairs, with its bare wood floors, mismatched shelves, untidy piles of books and magazines, and robust typewriter—a working room of a man who famously gave voice to common workers. Like many creative people, Sandburg and his wife, Lilian (known as “Paula”), were bibliophiles—book lovers. Extreme bibliophiles, in fact: their personal library ran to over 16,000 volumes, some 11,000 of which are in the possession of the park. The dominant feature of Connemara’s interior is its bookshelves, often extending from the floor to nearly the ceiling. Long after the Sandburgs’ deaths, just scanning the titles of their books can tell you a lot about their personal lives: bibliography serving as biography.

10. Adjusting and Readjusting:

Isle Royale National Park, Michigan

A typically rugged shoreline at Isle Royale National Park. (National Park Service)

An archipelago in the far northwestern corner of Lake Superior, Isle Royale seems remote, and it is, at least by American standards. The park, nearly all of which is a designated wilderness area, is reachable only by ferry, private boat, or seaplane. It has no roads, cell coverage, public telephones, or Internet service. Stormy or foggy weather can cancel or delay transit for days at a time. It is one of the few national parks (and the only one outside of Alaska) that truly demands visitors be self-reliant. It also demands something more subtle: the willingness to adjust your plans and expectations. You may have spent months planning that kayak trip to the park’s sublime finger bays at the northeast end of the main island, but if the wind is strong out of the east the day you planned to round treacherous Blake’s Point—the only practical way to get there—then you aren’t going. The question isn’t, Are you going to change your plans? Nature already decided that. The question is, Are you going to change your plans and still enjoy yourself? You can’t plan an answer to that question beforehand, but how you do answer it says a lot about the kind of person you are.

*Author’s Note, November 2023: My essay was originally written for Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective in 2016. Were I writing it today, I would include an important addition to the segment that describes Eero Saarinen’s central role in creating the Gateway Arch at Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. In 2018, the Memorial was redesignated as Gateway Arch National Park. As part of the relaunch, the park’s museum, which is located beneath the Arch, was completely redesigned to acknowledge the growing consensus that the Arch "honors historical events that are now understood as deeply problematic within the larger trajectory of American history, including the dispossession of Native American land, cultural genocide, the extension of slavery, centuries of conflict and ill will with Mexico, environmental degradation and the emergence of a myth of American exceptionalism,” as an article in the Washington Post put it at the time. While Saarinen’s remarkable architectural genius is in the spotlight in the video essay presented here, I ask viewers to keep this more complex and troubling context in mind as well.