This year we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Summer of Love. Be-ins and Love-in’s, the Beatles and Pink Floyd, love and drugs; the summer of 1967 saw a worldwide cultural revolution of political awareness, personal liberation, and notably of psychedelic exploration. The Summer of Love marked the coming out party for the counter-culture we now associate with the 1960s, a bacchanal of sex, drugs and rock-and-roll.

1960s hippies dancing at a festival.

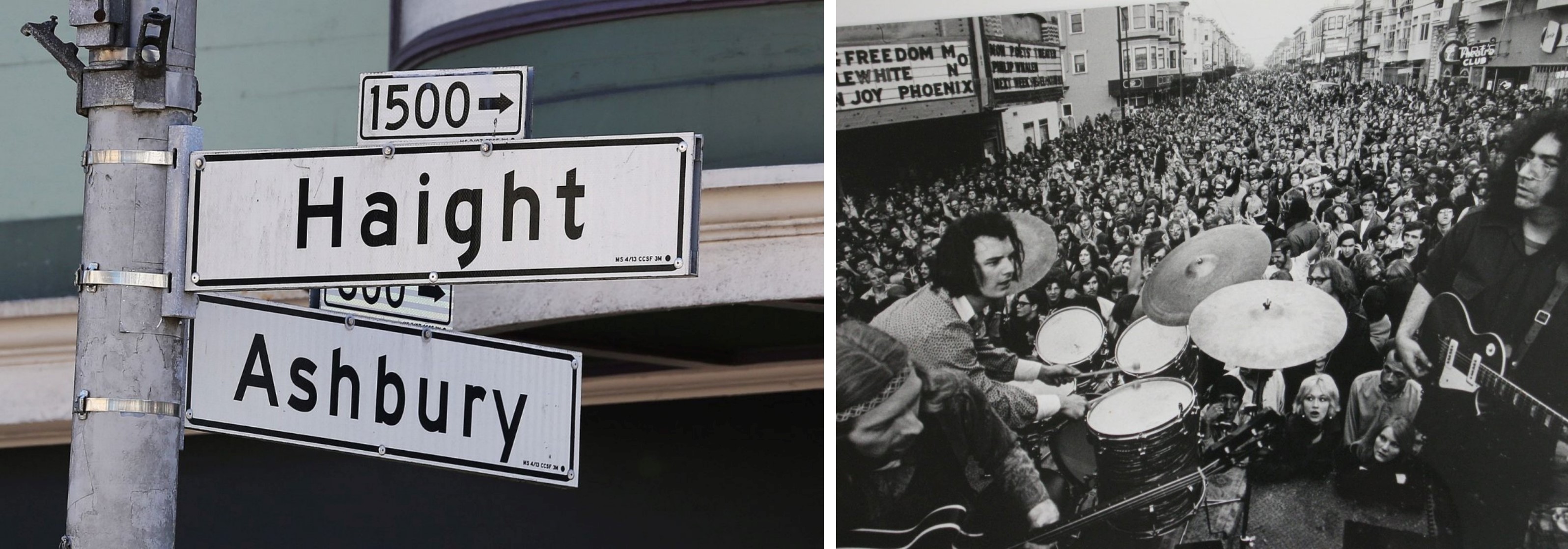

San Francisco was the American epicenter for the Summer of Love, and the term itself was coined there by a coalition of organizations. By 1967, San Francisco, and particularly the Haight-Ashbury section of town, had attracted thousands of hippies and other counter-culture types eager to take up psychologist and LSD advocate Timothy Leary’s advice to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

A variety of social, cultural, and geographic factors transformed Haight-Ashbury into the breeding ground for a cultural movement. University of California Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement in 1964 and Ken Kesey’s “Acid Tests,” which also helped launch the local San Francisco band the Grateful Dead, contributed to this locale’s claim to be the center of the hippie revolution. The Dead was one among several Bay Area bands that helped create a soundtrack for the summer of love. Others included Country Joe and the Fish and Jefferson Airplane whose dreamy sound seemed suited to mood of the moment.

The junction of Haight and Ashbury in San Francisco (left), and the Grateful Dead performing at Haight (right).

However, psychedelia emerged internationally, too, and London was another major center of this youth culture. When the UFO Club opened in London in December 1966, Londoners frequented the acid-drenched shows staged there by British psychedelia’s “house orchestra,” Pink Floyd. Emerging from multi-colored underground, Pink Floyd’s early records, namely Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), shaped the summer of love’s psychedelic, turned-on sound.

Playing to a dark den of tripped-out hippies, Pink Floyd’s loose, spaced-out improvisations in 1967 were at the fore-front of rock’s avant-garde. To the British public, the principal aspect of the Summer of Love was its music. To listeners today, the drug-propelled psychedelic rock of 1967 might sound a bit homogenous, but that’s not how it sounded at the time.

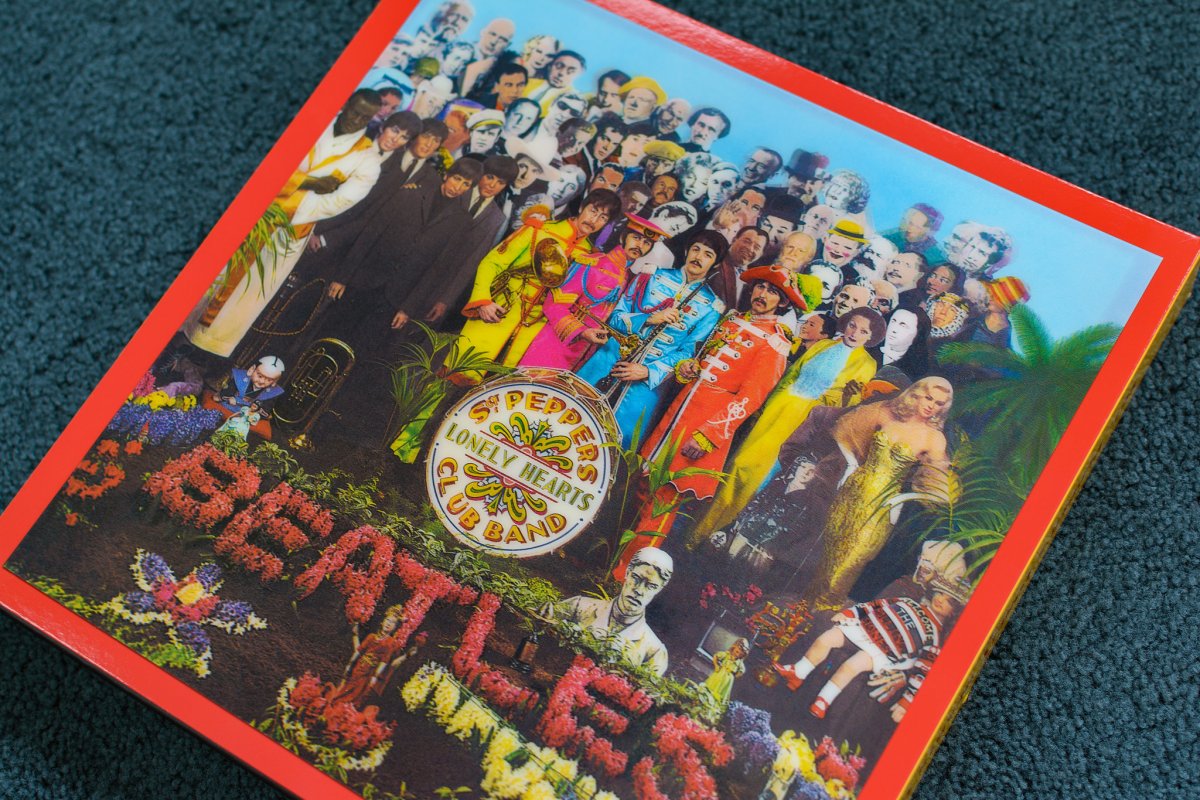

But without question, the greatest musical phenomenon of 1967 – and the most important British export to the United States during the Summer of Love – was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was received on both sides of the Atlantic with something approaching reverential awe.

The Beatles had begun recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in late August 1966, and was released on June 1 in England and June 2, 1967 in the United States. The quintessential psychedelic record, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, is a hallucinogenic take on English music-hall culture, which had been in decline in England since the 1930s.

That sound, a fusion of American R&B with British music halls, became enormously popular in the U.S. Beat poet Allen Ginsburg argued that the Beatles created a multi-generational work of art that helped defuse the tensions of the generation gap that had widened with the rise of counterculture.

On June 25, 1967, the BBC broadcast the Beatles singing “All You Need is Love” to an estimated 400-700 million people around the globe. That song served as an anthem for the Summer of Love and love itself became the symbol of the burgeoning cultural movement in 1967.

That ethos and the music associated with it were at the center of the Monterey Pop Festival, held June 16-18 down the coast from San Francisco about 100 miles. The Monterey Pop Festival pioneered the basic idea of a multi-day rock music festival that inspired Woodstock two years later, as well as the music festivals we see today. In comparison to today’s bloated ticket prices, admission for Monterey cost between $3 and $6.50 (roughly $25-50 today).

Michelle Phillips at the Monterey Pop Festival, 1967.

Monterey was “an artist-created event, intended to give pop music the same cultural weight as jazz and folk” said Eric Burdon of the Animals, who played at the festival. The festival co-founders, Lou Adler and John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, modeled Monterey on older jazz festivals, and convened a “board of governors”—including Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, and Paul Simon—to offer advice. The Beatles didn’t play there but they recommended the Who and Jimi Hendrix. Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead also played, and Janis Joplin broke out onto the scene.

D.A. Pennebaker captured it all on film. His festival film, Monterey Pop, created the concert’s now-iconic moments, like Jimi Hendrix setting fire to his guitar. The timing of the festival was just right to catch the spirit of the long-haired, anti-war, peace-and-love crowd. The film also captures the thousands of attendees who committed themselves to peace, love, and music in the shadow of the Vietnam War.

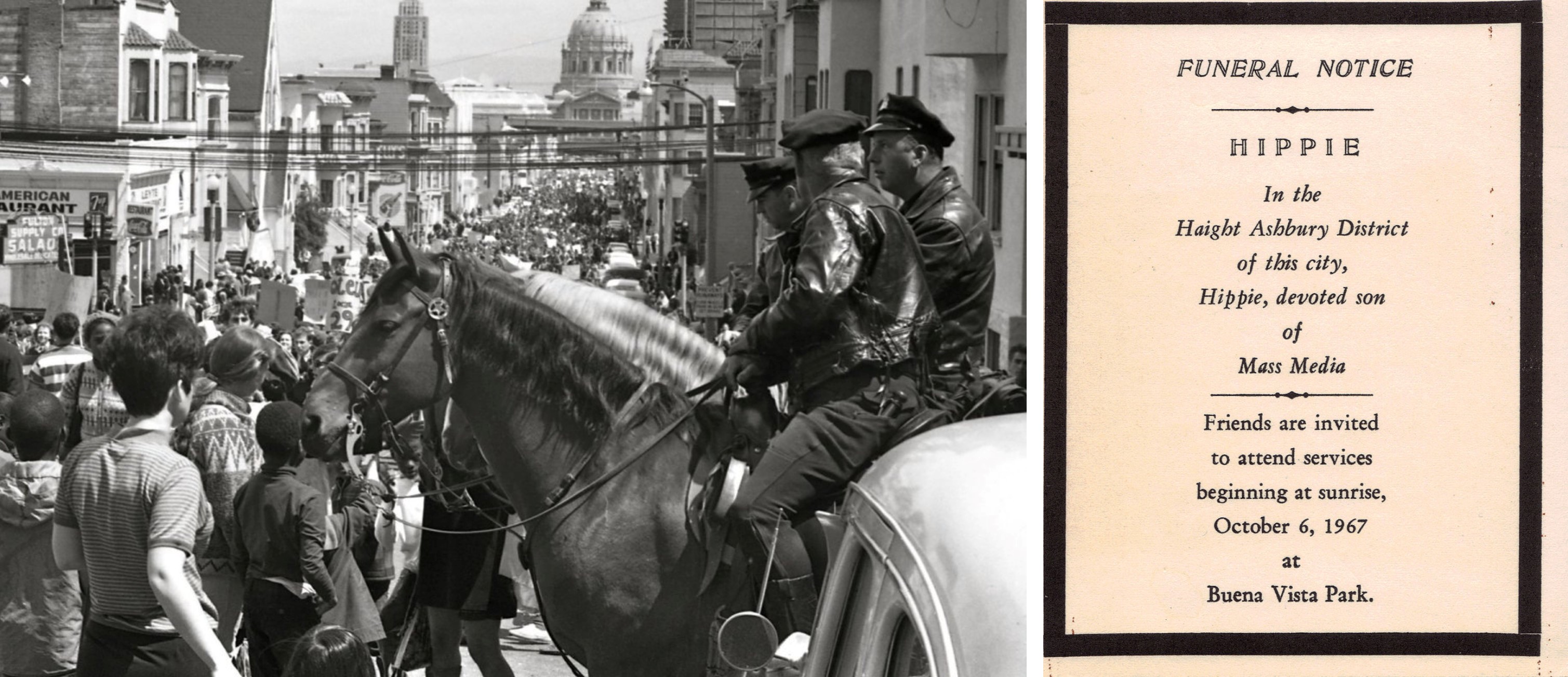

It is easy to consider the Summer of Love as a golden age, a moment of harmony and positive emotion that compares badly to the anxiety and fear of today. But there was a darker side. While some of the counterculture’s dreams came true, hippie idealism did not offer solutions to the world’s conflicts, especially the Vietnam War. After the summer ended, Haight-Ashbury, once the zenith of contemporary enlightenment, became a magnet for drop-outs, drug-addicted youths, and lost souls, a scene captured by Joan Didion in her essay “Slouching Toward Bethlehem.” Summer’s charm had quickly receded with the hippie tide.

A demonstrator offers flowers to military police during anti-Vietnam protests at the Pentagon, 1967.

Mounted police watch the Vietnam protest in San Francisco in April, 1967 (left), and a notice for a mock funeral held for the "Death of the Hippie" in San Francisco on October 6, 1967 (right).

A Monterey Pop Festival revival took place this summer exactly 50 years after the original with new and old-comers to the stage. Eric Burdon, Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead, Jack Johnson, and Norah Jones, daughter of legendary sitar player and original Monterey artist, Ravi Shankar, played at the 2017 festival revival. Lou Adler, consulting for the festival, offered advice and contributed items for an on-site exhibit consisting of original guitars, outfits, and other materials. What had been novel in 1967 had become commercial nostalgia by 2017.

The rise of Sixties counterculture has had a significant impact on our culture today. The proliferation of yoga studios and Eastern religions, more relaxed attitudes about drugs, and the popularity of music festivals as cultural (and commercial) gatherings can all be traced back to 1967. Maybe because we want to believe what Paul McCartney said—that it’s getting better all the time—that fifty years later we remember the Summer of Love and its legacy.