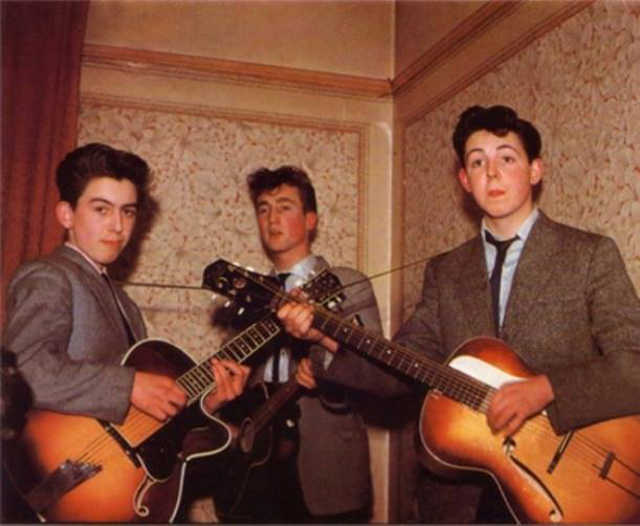

On February 7, 1964, the Beatles made their arrival in the United States. Stepping off an airplane at JFK, the fab four were met with deafening screams from their fans and flashbulbs from the many reporters who would inform the nation that a new kind of British Invasion had begun.

Little was that nation aware that these British gentlemen would help define American life for generations to come. In 1964, the relatively new musical genre of rock and roll was under siege. But after John, George, Paul, and Ringo brought the British Invasion across the Atlantic, rock and roll saw a resurgence that helped cement what many people called “race music” as a core part of American identity.

In the early twentieth century, white Americans coined the term “race music” to describe the blues and jazz music created by black artists. As white record producers began marketing these genres to their customers, white Americans sought a term to define this new part of the popular music market dominated by black talents. As blues and jazz made way for rock and roll and eventually rap, “race music” remained throughout the twentieth century a term applied to recordings of black artists sold to white listeners.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the physical and racial divide created by urban sprawl marked black America as different and prohibited for white youth. Restrictive housing practices and economic disparities limited housing options for black Americans. White adults moved their families to the suburbs, leaving minorities behind in the city. For a young white American who had spent her or his entire life in a carefully cultivated white suburb, black America was forbidden and foreign.

Surrounded by media defining young people as rebels (like James Dean) and stifled by a cookie-cutter middle class lifestyle, teens identified with rebellion. By bringing black voices into white homes, radio and records (along with clubs and concert halls) allowed these rebels and roustabouts quick access to what all rebels need: something taboo and off limits.

The consumer market made note of white suburban interest in race music and began to provide more of these records to complement the demand. Radio DJs like Alan Freed started playing black music and imitating the voices of black DJs. Then, white artists such as Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, and Bill Haley began to borrow from “race music.” As the talents of artists on both sides of the racial divide began to mix, Americans created a new genre: rock and roll.

By the late 1950s, though, rock and roll fell into a lull as white parents reacted negatively to the idea of their children identifying with black Americans. Many parents mirrored the opinions of the record executive, Mitch Miller, who complained in 1958, “Much of the juvenile stuff pumped over the airwaves . . . hardly qualifies as music.” Miller sought to shut down what he considered “juvenile” race music and the DJs that allowed white children to cross racial boundaries. However, like many parents, he masked the racial motivation of his complaint carefully when he spoke.

Frank Sinatra spoke for many parents when he said, “Rock and roll is the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression — lewd, sly, in plain fact, dirty.” Teenagers in 1955 sent 15,000 letters to Chicago radio stations to request that “dirty” songs, specifically rhythm and blues tracks, no longer be played.

Rock and roll was vulnerable at this particular moment in time because there were no big names left to hold it up. By the early 1960s, Buddy Holly had died in a plane crash, Elvis was making movies, Chuck Berry was in jail, and Jerry Lee Lewis was tainted by scandal. Record executives mindful of white parents’ complaints carefully cultivated white pop sensations such as Fabian and American Bandstand. These artists and their music occupied space on television and the radio that rock and roll had previously possessed.

Fortunately, Englanders along the river Mersey were still seeking inspiration from rock and rolls’ increasingly forgotten artists. Johnny and the Moondogs (soon to be the Beatles) was one of these bands. After Americans’ moral panic, only an outside source could bring race music back to the place of its creation.

With their high record sales, the fab four paved the way for other British Invasion bands to join this lucrative market and flood American listeners with the sounds of rock and roll. Rock and race music replaced Fabian, Pat Boone, and Perry Como at the top of the charts. And, according to Marshall Chess of the record label Chess Records, blues musicians liked “the fact that [the Rolling Stones] were covering their songs, and that, as a result, more and more people, particularly white people would become aware of their music.”

As white Americans adopted the outlaw rock and roll attitude of the Rolling Stones, they unknowingly identified themselves with a piece of black culture. In a twist on the moral panic that originally helped kill rock and roll in the 1950s, many white children since 1964 have continued to purchase and define their own experiences by music inspired or created by black Americans.

Concerns over race music have also continued. White parents of the 1980s worried about rap music, an anxiety that was institutionalized when Tipper Gore helped found the Parents Music Resource Center in 1985. In the 1990s, boy bands (like ‘N Sync and the Backstreet Boys) made rap more marketable to white children, and today Justin Bieber may be playing a similar role.

Fifty years ago, when the Beatles first arrived in the states, they became a crucial part of a larger trend towards the revival of rock and roll and, to this day, transformed the relationship among music, race, and American identity.

- All images via Wikimedia Commons and all videos embedded via YouTube