On April 24, 2015, much of the world will commemorate the centennial of one of the most highly contested events of the twentieth century: the Armenian Genocide.

In the midst of World War I and as the Ottoman Empire suffered through what we now know were its last years, Turkish officials oversaw the deportation and massacre of anywhere between several hundred thousand and 1.5 million Armenian people. The result was the physical annihilation of the Armenian communities that had lived in the Anatolian peninsula for more than 2500 years.

Yet, although Pope Francis recently called the killing of Armenians “the first genocide of the 20th century,” recognition of the 100th anniversary will not take place in Turkey, which has steadfastly refused to call the Armenian deaths a “Genocide.”

|

|

| Official symbol of the Centennial; The City Hall of Los Angeles colored purple in commemoration of the Genocide 2015. | |

For far too long two distinct stories about 1915 have been told: an Armenian history largely for Armenian readers; and a Turkish and Turkophilic history for Turks and their friends. The two literatures talked to the already converted; they confirmed what people wanted to believe and did not challenge assumptions with which people had grown up.

The two narratives were mutually exclusive, and dialogue between them was nearly impossible. One affirmed the genocide and lay blame squarely on the Turks. The other denied genocide and blamed the killing on war, civil war, or Armenian provocation.

The Armenian version was content to see the Genocide as giving all agency to the Turks and none to the Armenians, who became in this scenario passive and blameless victims. The Turkish version, which has been very successful in muddying the waters and in convincing many non-Armenians that the facts of the matter are in doubt, said something absurd, like “There was no genocide, and the Armenians are to blame.”

The Armenian version became sanctified and resistant to change or reinterpretation. The Turkish version has to the present time been supported by state authorities and state-supported writers who work assiduously to render the Armenian Genocide controversial. Their latest efforts are centered at the University of Utah and its press.

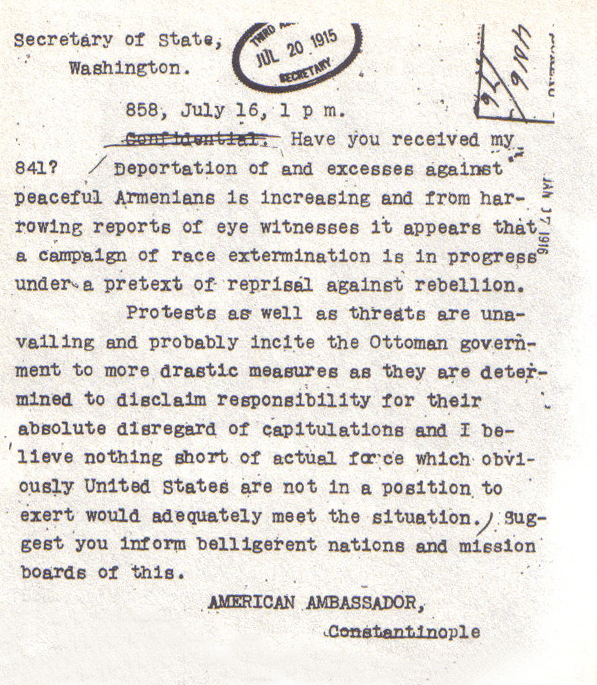

|

| American Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau, decried Turkey's actions in this telegram to the State Department. |

Despite more than eighty years of writing on the Armenian Genocide, key questions of why and when the Ottoman authorities ordered the deportation and massacre of hundreds of thousands of their own subjects remain unclear. Turkish state-sponsored efforts to cover up or deny a policy of genocide have been diligently countered by efforts by scholars to recover lost historical memories and collect documentary evidence in order to assess fairly the events of 1915.

Some successes are notable: a broader recognition and knowledge of the events of 1915 among the general public and among Armenians and Turks themselves; the establishment of institutes and programs to study systematically the Genocide; a number of official resolutions recognizing the Armenian Genocide; and an impressive amount of research and publication, a small fraction of which uses documentation from Turkish state archives.

One of the most effective efforts to expand our knowledge on the Armenian Genocide has been WATS (Workshop for Armenian-Turkish Scholarship) that from 2000 to the present has brought Turkish, Kurdish, Armenian, and other scholars together to discuss and write on the Genocide.

Until recently, neither version spent much time on causation, on explanation of why these events occurred. Armenian energy has been spent trying to create a factual record of the events themselves, to find indisputable documentation, little of which is reflected in Turkish versions.

Even Turkish scholars who find the more politicized accounts distasteful tend to avoid discussion of the Armenian massacres and deportations. For far too long hisatorial research dealing with the period of the war, the end of the Ottoman empire, and the foundation of the Turkish Republic managed to do so without any serious investigation into the removal of hundreds of thousands, upwards of a million or more, people.

|

| An Armenian woman leans over her dead child near Aleppo, Syria,1915. |

Rather than arguing that the Genocide was planned long in advance and was continuous with the earlier Ottoman policies, I contend that the brutal policies of killing and deportation (surgun) that earlier regimes used to keep order or change the demographic composition of towns and borderlands must be distinguished from the massive expulsions of 1915.

The very scale of the events of 1915, as well as their intended effects—to rid eastern Anatolia of a whole people—made the Genocide a far more radical, indeed revolutionary, transformation of the imperial setup.

As in earlier and later massacres of Armenians, victims and victimizers were of different religions, but these mass killings were not primarily driven by religious distinctions or convictions. Membership in a religious community (millet) was an important marker of difference, and religion closely corresponded to ethnicity, even in many cases to class.

|

| Armenian children deported or escaped from Eastern Anatolia find refuge in Aleppo, Syria. |

But the motivations for murder were not spontaneously generated from religion or even ethnicity but were driven by a cascade of influences: decades of hostile perceptions of the “other” and a Turkish sense of losing social status and wealth to Armenians , insecurity in the face of perceived dangers, and the positive support and encouragement of state authorities for the most lawless and inhumane behavior.

The Armenian Genocide was also not primarily a struggle between two contending nationalisms—Armenian and Turkish—one of which destroyed the other. Such a scenario presupposes that two well-formed and articulated nationalisms already existed in the early years of the war.

Among Armenians, divided though they were among a number of political and cultural orientations, identification with an Armenian nation had gained a broad resonance. Yet Turkish identity was not clearly focused on the “nation.” Turkish nationalism was still weak and mixed in with Islam, Pan-Turanism, and Ottomanism.

| Two Armenian refugees, a woman and her son, photographed above. |

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, the Young Turks) elite was not so much engaged in creating a homogeneous ethnic nation as it was searching, unsuccessfully—flailing around—to find ways to maintain its empire.

Deporting, killing, and forcefully converting Armenians were parts of a major, deliberate effort to that end, but not in order for the Young Turks to create a “Turkey for the Turks” or a homeland for the Turkish nation, something that in the next decade would become the hallmark of the Kemalist republic.

The imperial mission of the CUP still involved ruling over Kurds and Arabs, as well as Jews, Greeks, and even Armenian survivors, in what would essentially still be a multinational Ottoman Empire. In the vision of some, like Enver Pasha, that vision was now greatly expanded to include the Turkic peoples of the Caucasus and possibly Central Asia.

Even as some thinkers, notably ‘Turks” from the Russian Empire advocated an empire in the more ecumenical civic sense of the Ottomanist liberals of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the policies of the Young Turks never were purely Turkish nationalist but remained Ottoman in fundamental conception. In a word, they were primarily state imperialists rather than ethnonationalists.

Most analysts agree that in the first decade of the twentieth century there was a significant shift among the Young Turks from an Ottomanist orientation—in which emphasis was on equality among the millets within a multinational society that continued to recognize difference—to a more nationalist position in which the superiority of the ethnic Turks and their privileged position within the state was more explicitly underlined.

This steady shift toward Turkism presented the Armenian political leadership with an extraordinarily difficult choice—remaining in alliance with the increasingly nationalist Young Turks or breaking decisively with the government. The leading Armenian political party, the Dashnaktsutiun, decided to continue working with the Young Turks in the last years before World War I, while the Armenian Church leaders and the liberal Ramkavar party distanced themselves from the government party.

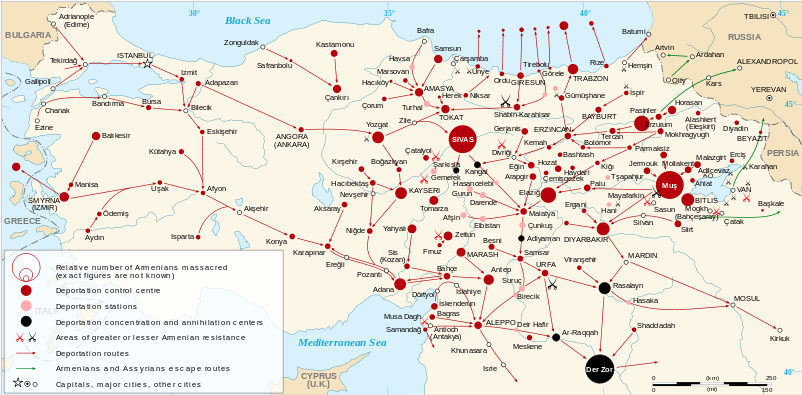

|

| This map depicts locations of deportation stations and routes as well as escape routes. |

Even when the Marxist Hnchaks denounced the Young Turks for their steady move away from Ottomanism toward Turkism and their failure to carry out agricultural and administrative reforms, the Dashnaks maintained their electoral alliance with the CUP.

When war broke out in 1914, the Ottoman Dashnaks pledged to fight for the empire and to urge Ottoman Armenians to join the Ottoman army, while across the border Russian Armenians, also influenced by the Dashnaktsutiun, volunteered for the tsarist army.

Armenians found themselves in armies on both sides of the Caucasian Front, and high officials of both empires harbored suspicions of Armenian disloyalty. But only one government decided to act preemptively to rid itself of its Armenian “problem.”

The argument often employed by Turkish leaders to the Western and German diplomats who inquired and protested against the treatment of the Armenians was that the precarious condition of the empire and the requirements of self-defense of the state justified the repression of “rebellion.”

|

|

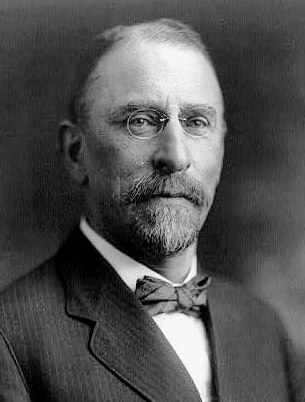

| Ottoman Interior Minister Talat Pasha; American Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau | |

In a telling interview with the American ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, Minister of Interior Talat conveyed the complex of reasons that influenced the decision to eliminate Anatolian Armenians.

“I have asked you to come to-day,” began Talat, “so that I can explain our position on the whole Armenian subject. We base our objections to the Armenians on three distinct grounds. In the first place, they have enriched themselves at the expense of the Turks. In the second place, they are determined to domineer over us and to establish a separate state. In the third place, they have openly encouraged our enemies.”

In his own terms the Minister spoke of the status reversal of Armenians and Turks (“they have enriched themselves at the expense of the Turks” and “are determined to domineer over us”), the government’s fear of Armenian separatism and the breakup of the empire, and the collaboration of Armenians with the Russians.

The deportation and mass murder of Armenians was not motivated primarily by religious fanaticism, though distinctions based on religion played a role. While most victims of the massacres were condemned to deportation or worse because of their ethnoreligious identification, there were many cases in which people were saved from death or deportation when they converted to Islam. The identity of Armenians for the Ottoman elite and ordinary Turks and Kurds was not as indelibly fixed as the identity of Jews would be in the racist imagination of the Nazis.

|

| This structure, known as Tsitsernakaberd, is Armenia's memorial to victims of the Genocide. |

In the end, Ottoman leaders and ordinary subjects lived within and were influenced by what I call an “affective disposition”—an emotional and cognitive environment—that had been created over time.

In that pathological emotional universe the Armenians were seen as grasping and mercenary, subversive and disloyal. They were turned into a alien and unsympathetic category that not only could be eliminated but had to be annihilated in order to save the empire.

Genocide occurred when state leaders determined that state security required the physical elimination of hundreds of thousands of their subjects.

Read more on the Armenian Genocide:

Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Goçek, and Norman Naimark, A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Goçek, and Norman Naimark, A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Ronald Grigor Suny, “They Can Live in the Desert But Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide (Princeton University Press, 2015). [Pictured left]

For a discussion of the efforts to deny the Armenian Genocide by constructing a theory of Armenian provocation, see Robert Melson, “A Theoretical Inquiry into the Armenian Massacres of 1894-1896,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, XXIV, 3 (July 1982), pp. 481-509; and “Provocation or Nationalism: A Critical Inquiry into the Armenian Genocide of 1915,” in Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian Genocide in Perspective (New Brunswick and Oxford: Transaction Books, 1986), pp. 61-84.

For a firsthand account, see Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Page, 1918), pp. 336-337