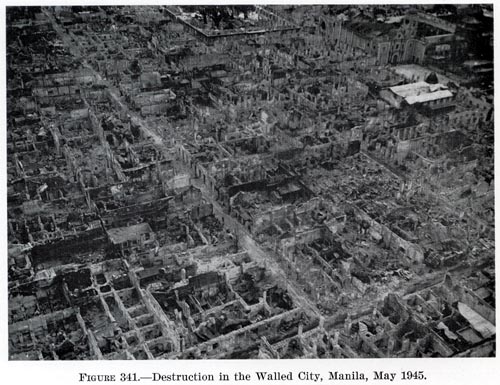

By the end of February 1945, the Philippine capital of Manila lay in ruins, caught between the American and Japanese war machines of World War II. A postwar investigation concluded that only Warsaw, Poland, saw a higher level of devastation.

Seventy years later, public memory of the battle for Manila includes a mixture of gratitude toward the Americans, nationalistic defiance, and horror. The event resonates in the history of a city that has long sat at the crossroads of competing powers, and it still looms large in the Filipino-American relationship.

|

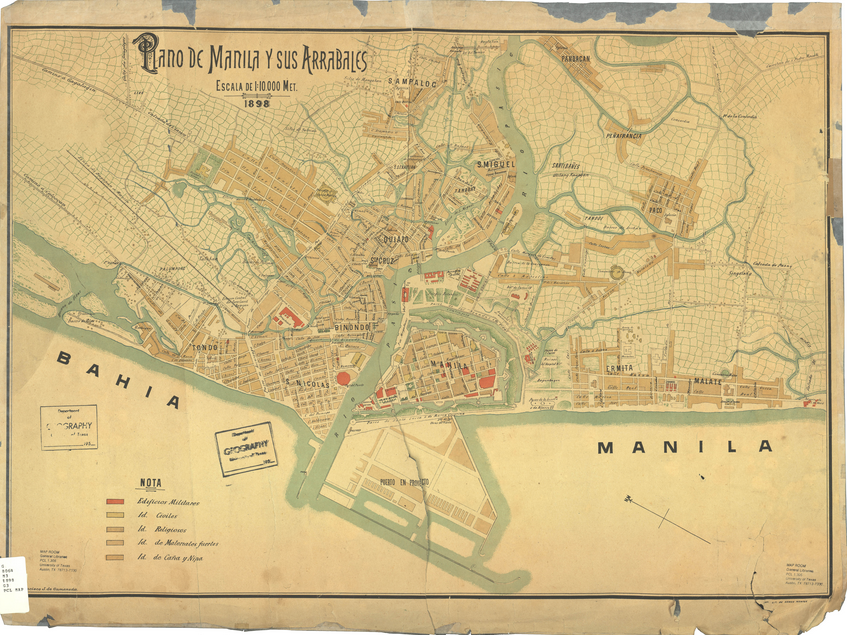

Map of Spanish Manila, 1898. The Intramuros district is just below center. |

The founding of Manila in the Western sense occurred in 1571. After destroying a Muslim settlement at the mouth of the Pasig River on the island of Luzon, Spanish conquistadors colonized the site.

Menaced by pirates and European competitors, the Spaniards continually improved upon their stone fortifications. The enclosed area, aptly named Intramuros (“inside the walls”), retained a distinct identity ever after, housing religious orders and cultural institutions.

The city thrived as a nexus of trade, linking the galleons of Spanish Mexico to Chinese merchants. Spain retained the city for three centuries despite challenges from the Dutch, the British, and the Filipinos.

|

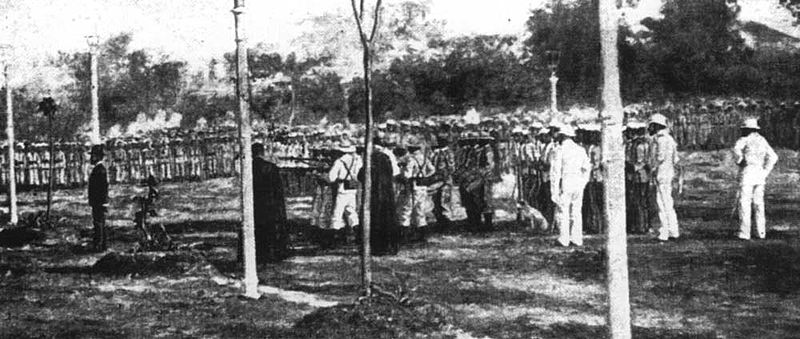

In May 1898, during the Spanish-American War, an American fleet destroyed the Spanish force in Manila Bay. Filipino revolutionaries proclaimed a new republic soon after, but the U.S. Army awaited word from Washington as to the political status of the Philippines. Fighting erupted on February 4, 1899, touching off the Philippine-American War. The conflict lasted three years and cost the lives of 6,000 Americans and 200,000 Filipinos. Politically, the violence tipped the scales in Washington in favor of annexation, and the Philippines became a U.S. possession.

|

As they pushed to democratize the Philippines, the new colonizers recast Manila in their image. A government district designed by architect Daniel Burnham strongly resembled Washington’s National Mall. Later additions, especially the Legislative Building (1918) and Manila City Hall (1941), enhanced the resemblance. Streets named after the U.S. states ran between the avenues of Dewey and Taft.

|

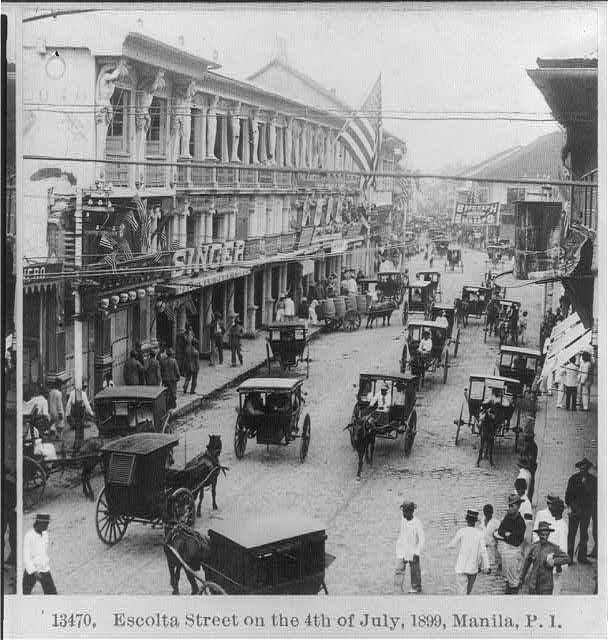

The Escolta, an historic shopping district, on July 4, 1899. |

American boosters hailed Manila as the “Pearl of the Orient,” borrowing a nickname coined by a Spanish Jesuit. The central districts displayed the best of American culture, which the press and educational system transmitted to the populace. Social barriers generally separated native Manileños from the Americans, with the exception of laborers, mistresses, and a small elite. Even during the Great Depression, Westerners lived well in a city where U.S. dollars went much farther than at home.

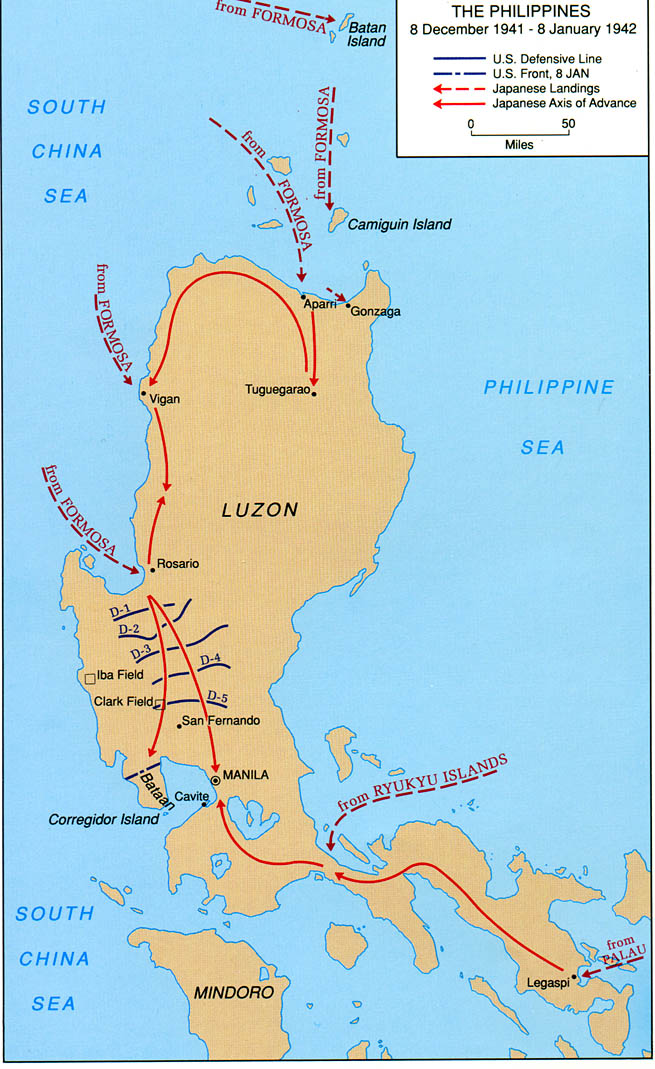

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Japanese bombed the Philippines, and they invaded Luzon a few weeks later. General Douglas MacArthur withdrew to the Bataan peninsula, declaring Manila an open city to save it from destruction, and the Japanese marched in unopposed on January 2, 1942.

|

The American headquarters on Corregidor Island surrendered in May, and the Japanese paraded the prisoners along Dewey Boulevard. Captain Manny Lawton of the 31st Infantry Regiment later reflected: “As we now marched down the great boulevard, hungry, weak, half naked, it was ludicrous to think that only ten months earlier it had been ours to exploit and enjoy.”

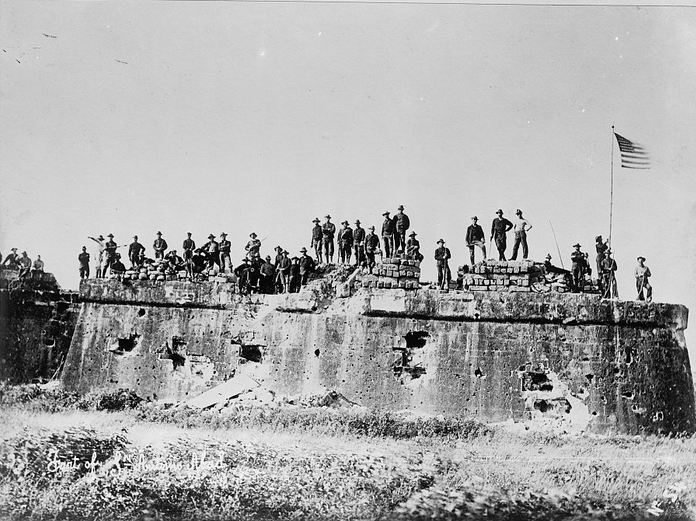

For three years Manila was part of the Greater East-Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Japanese did not transform Manila physically, but they altered place names, imposed a command economy, and gutted the American educational system. Fort Santiago, once used by the Spanish to torture Filipino revolutionaries, was now a hellish dungeon for American prisoners and suspected Filipino spies. The port became a crossroads for the Japanese military, hosting transient units on their way to and from distant battles.

Fort Santiago, operated by the Spanish, Americans, Japanese, and Filipinos. Photo by author. |

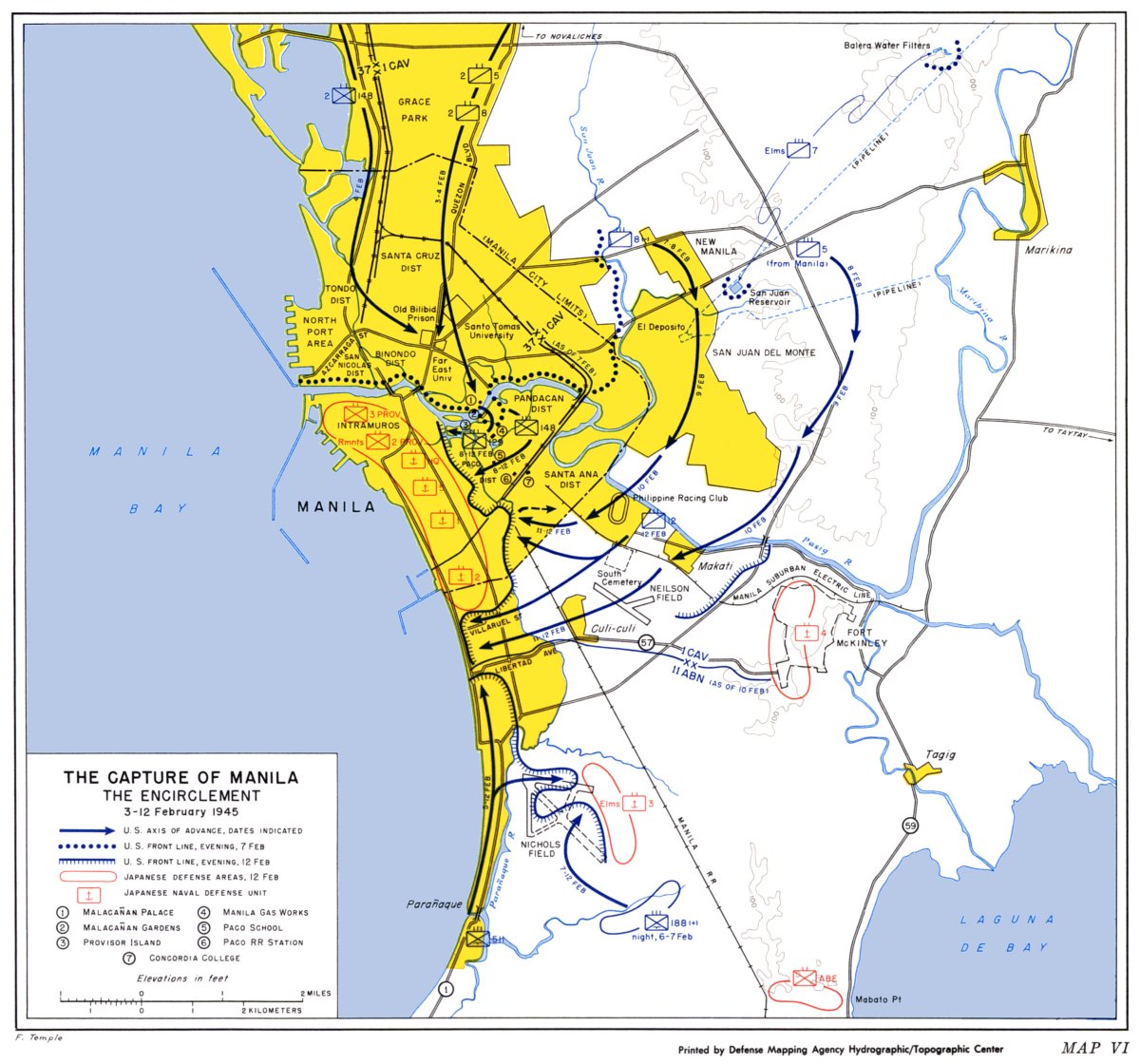

American conventional forces returned to Luzon on January 9, 1945. Fearing the execution of prisoners, the 1st Cavalry Division broke through Japanese lines and rushed to Manila, freeing internees at Santo Tomas University and Old Bilibid Prison by February 4.

By this time the Japanese commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, had ordered a withdrawal as MacArthur had done in 1941. The naval commander in the city refused, however, ordering thousands of troops to dig in. The decision doomed the city.

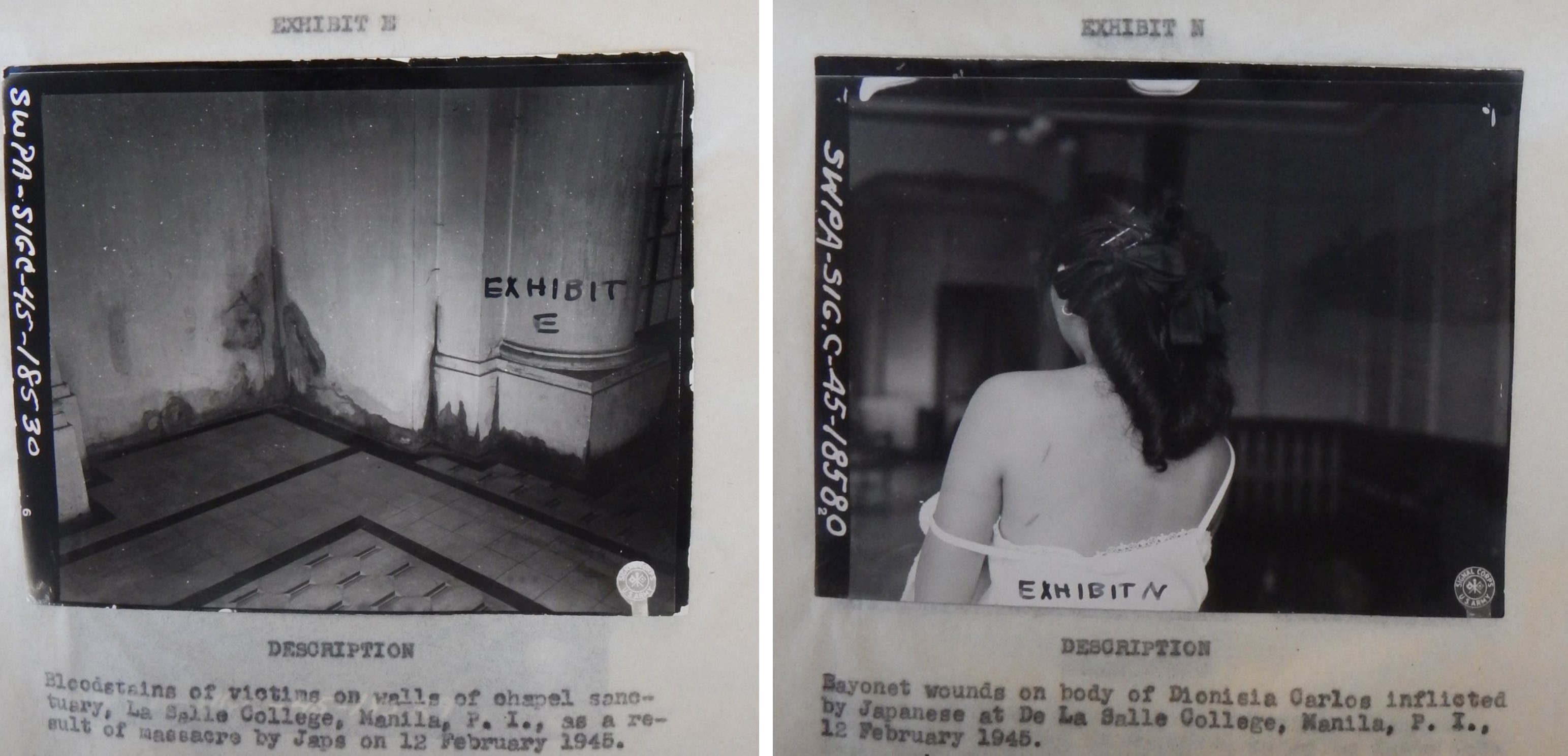

The events that followed are well documented in war crimes trial proceedings. As American forces pressed in, the Japanese tunneled, fortified, and set booby traps throughout the city. They torched supply caches and ignited whole neighborhoods to slow the invaders. Japanese soldiers systematically doused residences—and sometimes residents—in gasoline, while machine gun nests lay in wait for those fleeing the fires. Rape, pillage, and summary executions accelerated as the Japanese vented their rage on a populace they had never trusted.

|

If Japanese malice were not enough, the Manileños also faced indiscriminate American artillery fire. Meeting block-by-block resistance, U.S. forces poured shells onto the cityscape in an unabashed attempt to reduce American casualties.

As stated in the U.S. Army’s official history, the destruction was regrettable, but “American lives were understandably far more valuable than historic landmarks.” Omitted from this equation, of course, were the thousands of Filipinos who fashioned red crosses and white flags in a vain attempt to halt the bombardment.

Nevertheless, when the fighting ebbed, civilians swarmed the American lines. Having leveled entire city blocks, the GIs were astonished to see survivors. Even more shocking, many of the Manileños thanked them.

American ground forces inevitably closed in on Intramuros, the cradle of Spanish Manila. Howitzers blasted an entryway through the centuries-old walls, and shells blanketed the district as the invasion commenced on February 23.

|

Again, the Army’s official history: “That the artillery had almost razed the ancient Walled City could not be helped…. The destruction had stemmed from an American decision to save lives in a battle against Japanese troops who had decided to sacrifice their lives as dearly as possible.”

After Intramuros, a single pocket of resistance remained in the Washington-esque government buildings. On March 3, the last seventy-five Japanese soldiers, and one more American, fell dead.

The liberation claimed the lives of a thousand Americans, 16,000 Japanese, and 100,000 Manileños, one tenth of the population. Among the historic churches of Intramuros, San Agustin was the sole survivor. The remnants of the others sat idle until bulldozers cleared them in the 1950s.

The Philippines received its independence on July 4, 1946, as promised in 1934. While the new nation professed gratitude to its liberator-turned-colonizer-turned-liberator, nationalism rolled back American influence.

Manila street signs now featured guerrilla leaders and revolutionaries instead of U.S. states, and Dewey Boulevard became Roxas, after the first president. In the 1970s, officials began to shape Intramuros into an historic district, rebuilding the city walls and transforming Fort Santiago into a museum.

Memorializing the battle has been challenging for Manileños, as the trauma of 1945 makes it difficult to apply the term “liberation.”

Few probably support the far left’s theory that the devastation was a conspiracy to forestall independence, but resentment of the U.S. Army’s tactics is apparent in the writings of survivors such as Carmen Guerrero Nakpil and Joaquin Garcia. Others note that, in any case, the U.S. Army was preferable to the Japanese force that it expelled. Regardless, the word “liberation” has appeared only intermittently in official ceremonies, usually giving way to “The Battle for Manila.”

A restored parapet of Intramuros, with City Hall's clock tower in the background. Photo by author. |

In truth, the notion of a city-turned-battleground was not unique to February 1945. One has only to look to the circularities in the story, such as the Japanese making a stand within Spanish colonial fortifications, or the U.S. Army retaking a city that it defended against Filipino revolutionaries half a century earlier.

But by the end of the twentieth century, Manileños were eager to make the story their own. In 1995, for the fiftieth anniversary, Manila’s mayor convened Memorare, a committee dedicated to remembering the event from the perspective of its residents. The group’s correspondence, oral histories, and publications form a treasury of source material, housing the testimony of many who had never before shared their experiences. In these papers are countless tales of victimization, certainly, but also accounts of heroism and defiance in the face of unspeakable horrors.

The Memorare Monument. Photo by Author. |

Memorare has conducted subsequent anniversaries in a similar vein, always circling back to a rejection of violence. Its members focus not on liberation, nor on the battle itself, but rather on an appeal for international peace. And considering their city’s history from 1571 to 1945, and even to the present, it’s difficult to blame them.