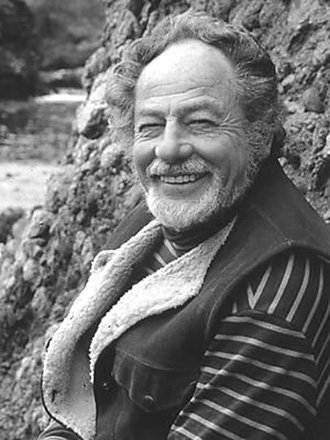

Lawrence Halprin (1916-2009), one of the most celebrated American landscape architects, would have turned 100 years old this month. Born to a Jewish family in the Bronx and raised in Brooklyn, with an upbringing he referred to as a “tribal” experience, he went on to design parks, gardens, and monuments around the country.

A self-declared Socialist, he spent several of his formative years outside of Haifa, then Palestine, working on a kibbutz (a communal farm). When Halprin returned to the U.S. he trained under modern architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Brauer at Harvard and was inspired by Frederick Law Olmsted whose work was pivotal in the creation of many of the National Parks.

Born in the same year that the National Park Service was created, Halprin worked primarily in urban settings. Influenced by the Modernism of his teachers, Halprin believed that the urban landscape functioned as the everyday backyard for city residents. He imagined that people would interact and engage with his spaces. Halprin declared that the modern landscape should be a real, tangible and visceral space. Unlike a park in the wilderness, people lived with the modern landscape not merely visited it.

His results have been mixed.

When Halprin designed the UN Plaza in San Francisco in 1977, he envisioned people interacting with a modern constructed landscape. Halprin’s design included a 165-foot-long fountain, with 673 blocks of granite weighing approximately three to four million tons. He was in love with the design and claimed to be the first designer to create a space that could actually be used by people.

The fountain commemorated the signing of the UN Charter in San Francisco, included a quote from Franklin Roosevelt, represented the seven continents of the world, and was designed with fountains operating on timed pumps mimicking the ebb and flow of the tides.

The UN Plaza is located where Market and Levenworth streets would have intersected, just South of the Tenderloin District. The “TL” as the Tenderloin is often referred, has been a high crime area with a large homeless population.

Critics ridiculed the plaza.

The fountain never worked as designed because the pump system was never maintained. The homeless moved in. Now nicknamed “urination plaza,” Halprin’s fountain, designed with hidden corners, became a public toilet, a place to have sex or for homeless to sleep. People did everything in the fountain. One individual interviewed in the 2004 documentary about the failure of the UN Plaza, “Biography of 100,000 square feet,” claimed that she witnessed an individual shoot up drugs at one end of the fountain, walk to the other end and die.

This was not the “interactivity” Halprin had in mind.

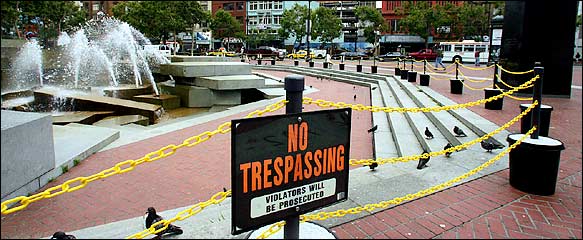

Ever since the fountain was opened, the city of San Francisco has been trying to fix its problems. A farmer’s market moved in to promote additional activity in the plaza, and the city took preventive measures to keep the homeless out such as removing benches, and in 2004, installing a yellow chain-linked fence around the fountain.

Today water continues to flow in the fountain (albeit still no pump-created tides), and the fence is gone, but many of its problems are still unresolved. Some say that the fountain’s issues are symptoms of bad design and others argue that the plaza itself disrupted the “natural” space of the city by blocking what would have just been a normal intersection, thus causing even more chaos in a high-crime area.

Halprin designed the UN Plaza a few years after he designed the FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C., though the latter was actually constructed decades later.

FDR never wanted a monument in his name after his death. “If any memorial is to be erected to me,” FDR declared in 1941, “I know exactly what I should like it to be…a block of stone about the size of this [desk]. I don’t care what it is made of, whether limestone or granite or whatnot, but I want it to be plain, without any ornamentation, with the simple carving ‘In memory of…’ That is all.”

But many of his devoted followers felt the need to remember him in some larger, more significant way. After the first design competition failed to impress the Memorial Commission in 1960, they asked Marcel Breuer to create a design. This too was rejected. In 1974, they brought Halprin in to foster narrative and create interaction.

Halprin had long since forgotten FDR’s Romantic vision of a pristine landscape, and desired to craft a modern landscape for his memorial, very similar in style to the UN Plaza fountain. The Commission approved Halprin’s idea for a 7.5 acre monument which employed the use of giant blocks of granite, seven fountains and pools, as well as sculptures, plantings, and inscriptions. The design included four rooms depicting Roosevelt’s four terms, four freedoms, and four continental time zones. This resulting memorial was dramatically more than FDR’s idea for a measly block of “whatnot.”

A section of Halprin's FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Twenty-three years after Halprin began work on the design, the memorial was opened to the public and I was one of its first visitors. In the spring of 1997 my high school classmates and I were on our senior trip to D.C. Shortly thereafter, the criticisms began.

Some critics complained about the aesthetics, others that the memorial was too didactic. A few antisemites even criticized the fact that three of the five sculptors who worked with Halprin were also Jewish (Leonard Baskin, Neil Estern and George Segal).

Visitors, however, loved the memorial. In fact, popular historian Doris Kearns Goodwin claimed it was her “favorite spot on the National Mall.” Before he died in 2009, Halprin explained that he “made [the memorial] a narrative, and wanted people to learn about Roosevelt through all the senses, not just sight.”

Visitors interact with Halprin's FDR Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Today, the memorial is considered a success. The bronze sculptures have areas of wear where they’ve been touched over and over again, and visitors gaze into the fountains and read well-known quotations as they collectively remember this former president.

Halprin had the same goal in mind in San Francisco and Washington: to use Modernist landscape design to create a narrative and foster interactivity. The UN Plaza interrupts the flow of the living breathing Tenderloin District of San Francisco. While of the same natural products, stone and water, the UN Plaza fountain is not natural: it is a crafted narrative in a naturally urban place.

By contrast, the FDR memorial does not disrupt the “natural” space and flow of the city of Washington, D.C. The FDR memorial, surrounded by other memorials, built for tourists not citizens of the District, is an artificial space created for such a monument.