Fear of cataclysm often numbs. It renders the trembling disoriented and inert, unable to imagine how to act. Sometimes the universe acts so powerfully that no human response could counter it.

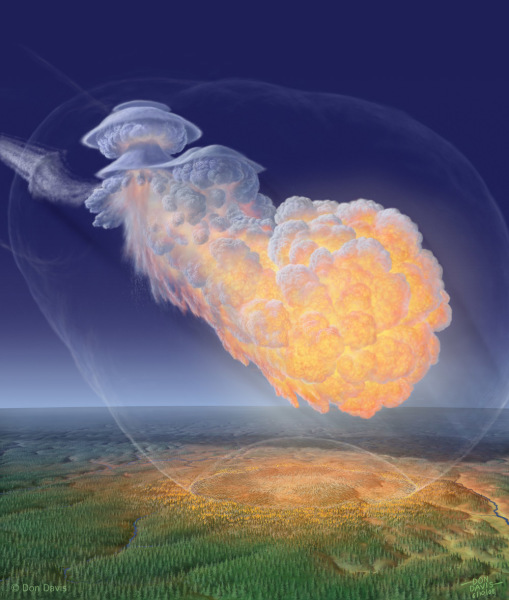

Artist’s rendering of the Tunguska event of 1908.

No disaster scenario more challenges human hopes to overcome nature’s forces than the sudden and unpredicted strike of a giant asteroid. Dark objects traveling through space have the potential to do us all in. Sixty-five million years ago an enormous rock wiped out the dinosaurs. If a dino-apocalypse can happen, so too can a homo-apocalypse.

This miniscule possibility becomes all the more unnerving because increasingly scientists know how much they don’t know. In recent years, efforts to monitor so-called near-earth objects (NEOs) have produced an impressive tally of the number, size, and trajectory of asteroids in our solar system. Researchers now envision scenarios for bumping menacing space debris out of earth’s way.

But the even greater insight of this endeavor has been to realize how many undetected asteroids exist out there. A collision still seems unlikely given the size of the solar system and estimates on the quantity of near-earth objects, but there is also little confidence that we would see one coming. In April 2018, for instance, an undetected asteroid possibly as wide as 360 feet passed by the planet at a distance closer than the moon.

On June 30, 1908, a massive mysterious explosion of a cosmic body shook the skies of Tunguska (in Siberia), on a date that would come to be known as International Asteroid Day.

Map showing the location of the Tunguska explosion.

Tunguska looms large in contemplating the threat of asteroids and other near-earth objects. But all these years later, we still aren’t exactly sure what happened there. Even unequivocally labeling the culprit behind the explosion an asteroid belies what events in Siberia from over a century ago might teach us.

What do we know?

Akulina and her partner Ivan experienced the event firsthand. They were in their tent near the Chambe River on the morning of June 30, 1908 (June 17 according to the Russian calendar at the time). The couple and their guests were all Evenks—an indigenous group that resides in central Siberia.

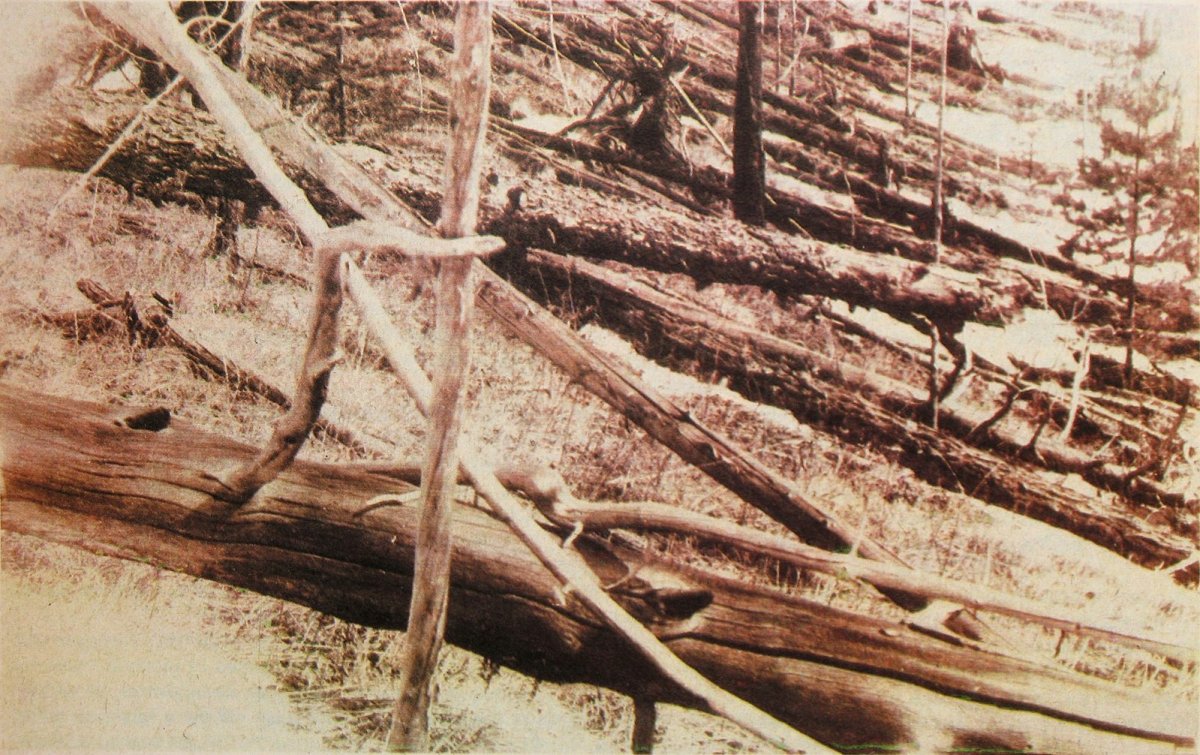

The site of the Tunguska explosion in the late 1920s.

As Akulina later recalled, something suddenly hit her tent and “I was scared, screamed, and woke up Ivan.” As they got up, the tent shook again knocking them over. They heard a thunderous noise, saw blinding light, and felt intense heat that burned their skin. Injured and coping with the destruction of their belongings, the group survived the cataclysm. At least two others appear not to have been so fortunate.

Throughout the desolate stretches of Siberia, hundreds of people noticed the event. With the aid of their testimony, scientists pieced together the following account.

A massive explosion occurred near the Stony Tunguska river that morning. The blast packed a punch equal to thousands of Fat Men and Little Boys, the weapons that the United States used to massacre Nagasaki and Hiroshima. It scorched and flattened forests in a radial pattern over a territory surpassing the girth of the Great Smokey Mountains National Park. Luminous clouds throughout much of Eurasia and beyond brightened nights surrounding the event.

Leonid Kulik, the first major Tunguska researcher, described initially glimpsing the site in 1927:

“I still cannot sort out my chaotic impressions of this excursion. …From our observation point no sign of forest can be seen, for everything has been devastated and burned, and around the edge of this dead area young twenty-year-old forest growth has moved forward furiously, seeking sunshine and life. One has an uncanny feeling when one sees thick giant trees snapped across like twigs, and their tops hurled many meters away to the south. This belt of growth surrounds the burnt area…and beyond is the taiga, the endless, mighty taiga, for which terrestrial fires and winds hold no terrors.”

Radially fallen forest at the site of the Tunguska explosion.

These images did not allow Kulik to make sense of “the whole majestic picture of this unique meteorite fall.” Convinced from the evidence before him that there should be fragments of a ferrous space rock, Kulik spent the better part of the next three years in the Tunguska taiga trying and failing to find it. The search involved grueling labor aided by the knowledge and know-how of locals. It nearly killed some of those involved, including Kulik himself.

The absence of evidence of a meteorite led to more searches and even more speculation. Scientists in the Soviet Union and abroad began to ponder whether Tunguska could have resulted from part of a comet or cosmic dust.

Eventually science fiction writers offered their own ideas. Writing after the nuclear detonations that ended World War II, Russian writer Alexander Kazantsev suggested a nuclear explosion had leveled Tunguska. Of course, the only way a nuclear explosion could have occurred in 1908 was if… an atomically-powered space craft from another planet blew up over Siberia!

From this point forward, endless explanations were offered about aliens and the paranormal at Tunguska. After the end of the Cold War, some have suggested that Nikolai Tesla triggered Tunguska by experimenting with his secret death ray.

Yet there was no neat division between science and fantasy in the history of Tunguska research.

Inspired by Kazantsev’s story, an independent cohort of scientists began making annual expeditions to the site of the explosion in the late 1950s. When they began, they wanted to determine if a guest from outer space had visited. Yet their commitment to empirical research superseded their enthusiasm for aliens.

A view of the Tunguska area today. (Photo by L. Pelekhan')

Over time members of what was called the Complex Amateur Expedition cooperated with mainstream scientists at the Academy of Sciences and supplied extensive data for astrophysical analysis. New Tunguska hypotheses about an ice core of a comet, geotectonic processes, and alternative types of asteroids have been put on the table thanks in part to their efforts.

If science has been linked to fantasy, Siberia connects to the cosmos. The buggy and boggy environment of the Tunguska taiga has served as an astronomical laboratory since the 1920s.

Tunguska researchers have been driven to know what happened, but not ready to settle and move on when unable to come to a conclusive consensus.

Knowing that a near-earth object could destroy everything demands patience and humility as much as urgency and confidence about the ability of science and technology to respond.