Russia’s February Revolution turns 100 this year. Less well-remembered than the October Revolution, which ushered in the Bolshevik takeover of Russia and creation of the Soviet Union, the events of February 1917 brought an end to more than three centuries of Romanov rule in Russia and set the stage for the later birth of the world’s first socialist state.

Demolition of Alexander III Monument, Moscow 1918.

Fueling this “February Revolution” were the mounting strains that the First World War placed on the deeply conservative Romanov Empire, whose tsar jealously guarded his autocratic prerogatives in the face of the mounting stresses that waging a modern war imposed.

In Petrograd—as the too-German-sounding “St. Petersburg” was renamed during the war—cracks appeared in the form of severe food and fuel shortages during the winter of 1916-17. These were deepened by the unusually cold weather. Throughout that frigid February, supply trains stopped rolling, bread queues lengthened, factories doors closed, and workers found themselves laid off.

Then the weather turned. On February 23—March 8 on the Western calendar—Petrograd thermometers hit an unseasonably warm 8 degrees (46 F). Thousands came out not only to take in the fresh air and celebrate International Women’s Day, but to vent long-simmering frustrations.

Znamenskaia Square in Petrograd during the February Revolution, 1917.

The mild weather lasted for weeks; the Romanov Dynasty did not.

The International Women’s Day crowds were only the beginning. The days that followed saw snowballing numbers of protestors, bloody street battles with police, and, crucially, the mutiny of soldiers tasked with quelling the protests. Alarmed, Chairman of the State Duma Mikhail Rodzianko pleaded with Tsar Nicholas II to undertake reforms.

The urgency of the moment is palpable in a telegram Rodzianko sent Nicholas on the 26th: “Serious situation. Anarchy in the capital. Government paralyzed . . . In the streets, disorderly shooting. One detachment of the troops fires on the other. It is essential to nominate immediately a person possessing the confidence of the people to form a new government. To delay is impossible.”

The tsar did not reply, instead complaining that “Again that fat-belly Rodzianko has written me all sorts of rubbish, to which I will not even respond.” But as the next few days made unmistakably clear, the tsar’s authority had evaporated. On March 2, Nicholas abdicated in favor of his brother Mikhail—who, in turn, declined the throne. And with that, the era of Romanov rule and, indeed, tsarist autocracy in Russia came to an abrupt end.

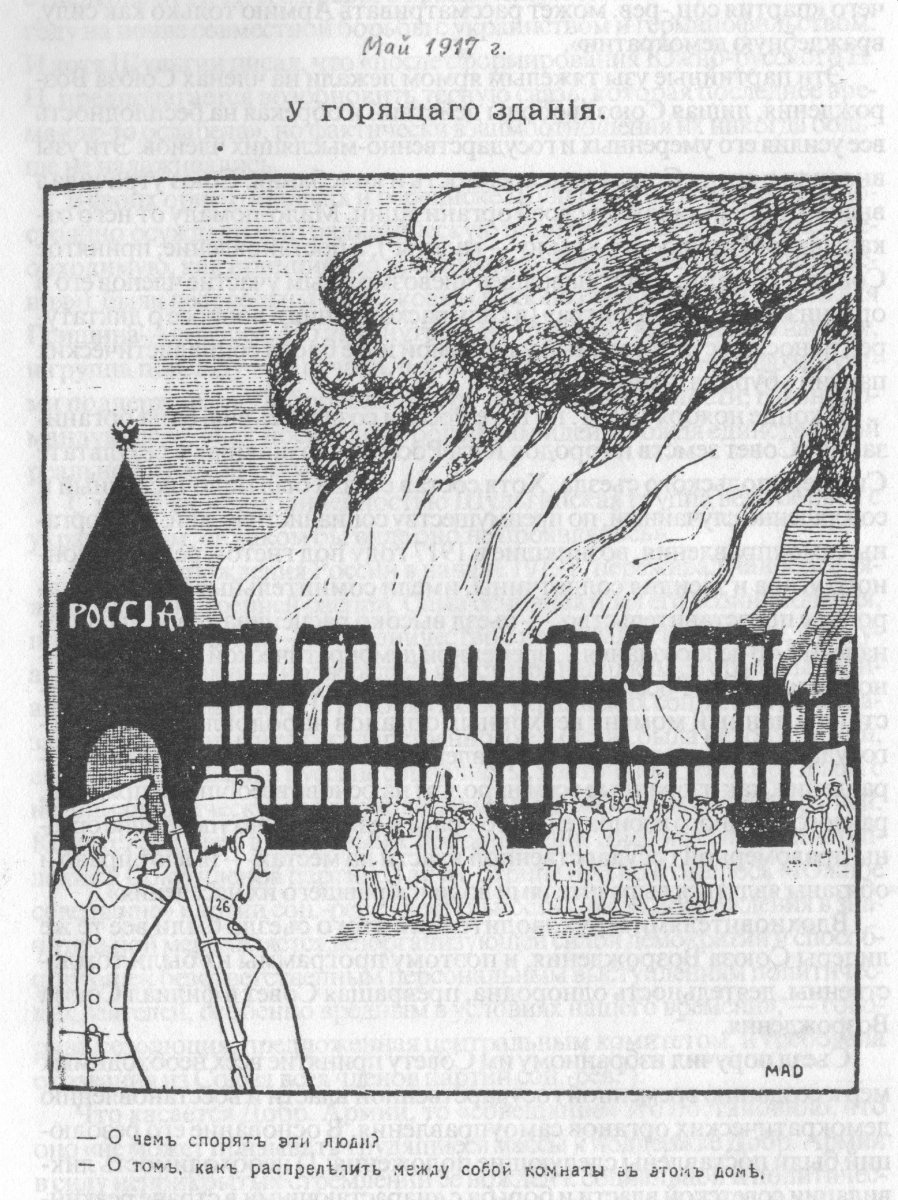

"Would you like to have a seat on the throne?" Russian cartoon, 1917.

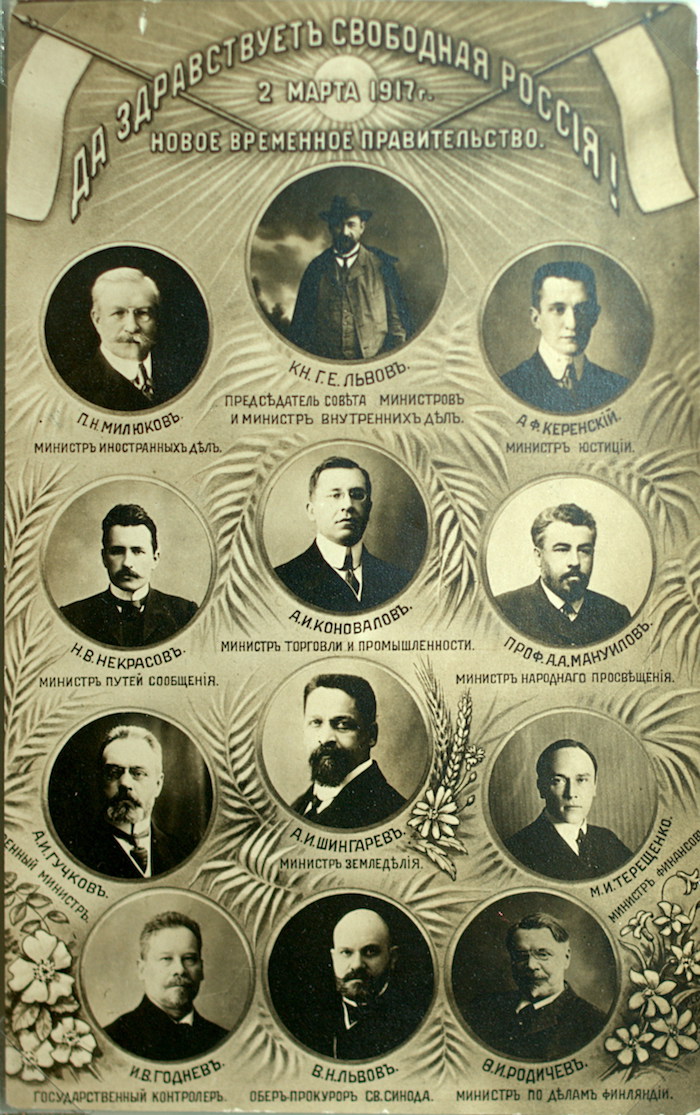

The hastily organized Provisional Government immediately set about enacting a spree of liberal reforms: the introduction of universal suffrage; abolition of legal restrictions based on religion, heredity, and nationality; freedom of speech, assembly, and the press; amnesty for thousands of political prisoners and exiles; elimination of Siberian exile and the death penalty.

Practically overnight, Russia had become, at least in Lenin’s famous description, “the freest country in the world.”

But the months followed were tortuous. The Provisional Government not only lacked legitimacy, it faced a near-impossible task: to govern a massive, incredibly diverse empire that had no firm social basis for liberal government, no real experience of the rule of law, and a centuries-long tradition of autocratic governance. The government’s shaky status was made painfully obvious by its full title: “The Committee of Members of the State Duma for the Restoration of Order in the Capital and for Relations with Persons and Institutions.”

Poster with portraits of Provisional Government Members, 1917.

Moreover, 1917 was a time of “dual power” even in the capital. Many Russians looked for direction not to the Provisional Government, but to the more radical Petrograd Soviet (“Council”) of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. That the Provisional Government continued to send Russian troops to be slaughtered in the Great War only further eroded its authority.

The situation facing so many former subjects of the tsar is captured brilliantly in Ali and Nino, a novel about the Great War and Revolution in Transcaucasia. Ali, the novel’s protagonist, learns of the February Revolution from a friend in Baku: “Hear me: great things have happened in our town. The prisoners have left prison and are now walking about freely. ‘Where are the police?’ I hear you asking. Behold—the police are now where the prisoners used to be. . . And the soldiers? There are no soldiers anymore, either. . . [T]here isn’t a tsar anymore either. There just isn’t anything anymore.”

Revolution, Memory, and Nostalgia

The meaning of the February Revolution today can be more fully understood by looking back to another recent centennial, that of Russia’s entry into the First World War in 1914.

As those who have visited Russia know well, the First World War can seem invisible in a land where the Second is omnipresent. Known to Russians as the “The Great Patriotic War,” World War II is commemorated not only in stately spaces such as Moscow’s Victory Park, but in such tiny villages as Khuzhir on Lake Baikal’s Olkhon Island, where one finds among the cows that snooze on the village’s dusty roads a proudly maintained memorial to the 97 residents—mostly Buriats native to the island—who died on a front three thousand miles from home.

WWII Memorial in the village of Khuzhir on Lake Baikal's Olkhon Island. (Photo by author)

Russian President Vladimir Putin reflected on the Great War’s relative invisibility in the speech he delivered on August 1, 2014, a century after the outbreak of the war. “World War I,” he explained, “which the rest of the world calls the Great War, was erased from our country’s history and was labelled [during the Soviet period] simply ‘imperialist’.”

He spoke before a monument “To the Heroes of the First World War,” a newly unveiled addition to Moscow’s Victory Park. Like most of the Russia’s public spaces, the park previously had no trace of WWI, a conflict deemed unfit to be honored alongside the victories over Napoleon and Hitler. But this new monument was essential, Putin claimed. Not only would it honor the generation who fought for Russia in WWI, but it would also serve as a “warning and reminder to us all of our world’s fragility.”

Putin used the speech to deliver two messages, the first aimed at an international audience, the second at a domestic one. Speaking just weeks after Russian-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine downed Malaysian Airlines Flight 17, killing all 298 aboard—the deadliest shoot-down of a passenger airliner in history—he explained that the July Crisis of 1914 should serve as a cautionary tale.

In the march to war, he maintained, the Russian Empire did “everything it could to convince Europe to find a peaceful and bloodless solution.” The tragedy that followed “reminds us what happens when aggression, selfishness and the unbridled ambitions of national leaders and political establishments push common sense aside, so that instead of preserving the world’s most prosperous continent, Europe, they lead it towards danger. It is worth remembering this today.”

Nobody who had followed the diplomatic crisis sparked by Russia’s annexation in Crimea in April 2014 would have missed the allusion.

Putin’s message to his domestic critics was less direct, but unmistakable.

Angst about the “color revolutions” along Russia’s borders and “Arab Spring” in the Middle East had long been a counterpoint to the self-assuredness of Putin’s rule, and his government had been shaken by significant protests in Moscow in the winter of 2011-12. This context would not have been lost on those listening when Putin asserted that the First World War ended badly for Russia because “victory was stolen from our country . . . by those who called for the defeat of their homeland and army, who sowed division inside Russia and sought only power for themselves, betraying the national interests.”

But Putin was playing the politics of nostalgia.

Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra in Seventeenth-Century dress, 1903.

His story of Russia’s First World War left the Russian Empire blameless: external enemies dragged her into the war, internal enemies betrayed her after it began. And in casting Russia’s loss in the war as the work of the Bolsheviks, he omitted the fundamental process at work in 1917: the imperial collapse well underway before Lenin and company seized power in October.

Far from a story of schemers stealing victory from the country, Russia’s exit from the First World War must be understood within the yawning power vacuum that consumed the country in the wake of the February Revolution.

This is a point worth emphasizing today, particularly when one considers the shapeshifting image of the past in today’s Russia. The Romanov Empire, not least because it now lies conveniently beyond the horizon of lived experience, has served as a rich trove of stories, symbols, and characters—a “useable” past—with which Russians have crafted a national narrative during the wrenching post-Soviet years.

But however alluring its image for many Russians today, it was an empire with profound problems. The anarchy that confronted Russians in 1917 was, after all, overwhelming not least because Russia’s last tsars, when facing the challenges of a rapidly changing world, too often clung to an imagined past as an antidote to a troubling present, rather than undertake reforms that might have made the empire more resilient. Their fear of subversive plotters, one might say, ultimately proved more damaging than the plotters themselves.

Maybe the lesson that February 1917 has to offer in February 2017 is that we would do well to spend less energy talking of making things “great again,” and more assessing the past in a sober fashion—less time indignantly calling for a “return” to a past that is gone, and more imagining a desirable future and sensible routes toward it.