The region of western Ukraine makes up just a small percentage of the territory and population of present-day Ukraine, but has historically played an outsized role in the 20th century struggles for control of eastern Europe.

It was here that the collapsing Habsburg and Romanov empires fought a doomed battle in World War I and where Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union embarked on their plans to divide and conquer Europe.

Beyond its international significance, this region has also been central to Ukraine’s complex journey to define itself. In the Soviet era and in Russia today, this journey has been reduced to just one story: the impact of radical nationalism. But there are indeed many war stories to be told about west Ukraine and its diverse population.

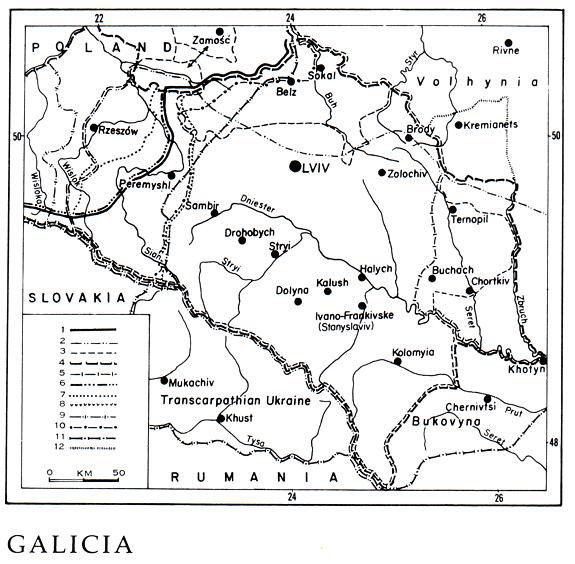

West Ukraine most often describes the territories that once made up the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia, a territory that found itself part of the Habsburg Empire, interwar Poland, and Soviet Ukraine all within the first four decades of the 20th century.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, when Ukrainians from this region were attempting to build a national movement with those they viewed as their compatriots living in imperial Russia, rich and often contentious debates ensued about how to resolve the differences that resulted from different historical experiences.

Galician Ukrainians were a product of a specific Habsburg political culture, while other Ukrainians found themselves shaped by the particularities of life in the rapidly changing Russian empire.

Even a common religious foundation eluded these groups, with Ukrainians to the east members of the Orthodox Church and Ukrainians in Galicia part of the Greek Catholic (Uniate) Church, an Eastern rite Church that shared common rituals with Orthodoxy, but recognized the authority of the Pope and operated in partnership with Catholic religious institutions.

Over time, the rise of nationalism meant that by the outbreak of World War II, locals increasingly saw themselves in national terms, divided between Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews. Yet a tension always remained between these national categories and the particularity of this place.

The story that typically gets told about west Ukraine is that because of the destructive impact of World War II, this region’s multi-cultural character disappeared.

For example, from 1939 to 1941, in the name of “liberating” the population from the Polish old regime, Soviet authorities deported, arrested, and executed local Poles. When Nazi Germany occupied this region beginning in 1941, they began systematically murdering the local Jewish population.

When the Red Army returned, mass violence continued to characterize the region, with radical Ukrainian nationalists fighting Soviet power and carrying out campaigns of violence against Polish civilians and Jews.

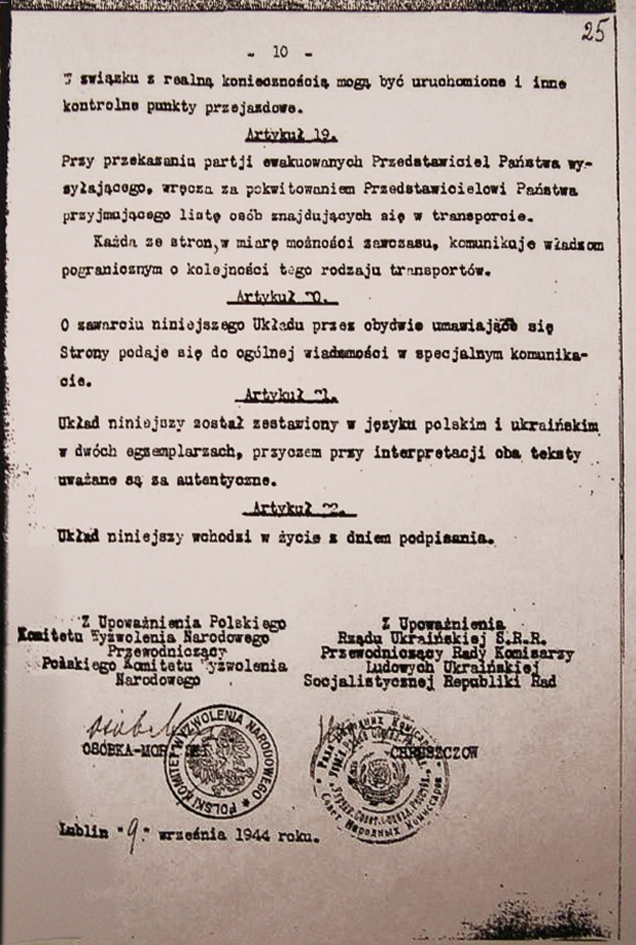

When Soviet control had been re-established in west Ukraine in 1944, the Soviet state carried out “population exchanges” with neighboring Poland, forcibly deporting Ukrainians from Poland to this newly Soviet west Ukraine and deporting the remaining local Polish population to Poland.

The population that remained was nearly entirely ethnically Ukrainian.

Yet, in the immediate postwar years, there was a significant diversity of experiences among those that the Soviet state, now in control of the region, deemed “Ukrainians.” These Ukrainians were a mix of locals, Ukrainians deported from Poland to the USSR, and Soviet Ukrainians sent to west Ukraine from territories to the east to build the Soviet state.

Along with their place of origin, the Ukrainians who came to inhabit the newly Soviet territory of west Ukraine were also distinguished by their wartime experiences. Some fought for the Soviet cause in the Red Army. Others fought as partisans for an ultra-nationalist vision of a Ukrainian nation-state, collaborating with the Nazi occupying regime in the hopes it would help them achieve their goals.

Some were arrested and deported to the Soviet interior by the Stalinist secret police. Others were arrested and sent to concentration camps by the Nazi Gestapo. Ukrainians who remained in Nazi occupied territory suffered immensely under policies meant to starve and subjugate Slavs, who the Nazis viewed as a lower race.

Among all these war stories, it was difficult to recover even the most basic of shared experiences. There was not even a common understanding of when the war began and ended. For those who had been living in Soviet territory, the war began when the Nazis invaded the USSR in June of 1941. For those living in west Ukraine, the war began when the Soviets annexed eastern Poland in September of 1939.

As the Stalinist state worked to make this territory and its people Soviet after 1944, the debates that took place on questions of what it meant to be Ukrainian and how to make sense of the diversity of wartime experiences had to play out in an atmosphere of strict control and terror.

And as the Soviet state openly embraced Russian nationalism after victory in the war, what it meant to be Ukrainian became increasingly tied to acknowledging the influence of Russia as an “elder brother” for Ukraine. West Ukraine’s historical separateness from Russia and the non-Russian cultural influences that made such a large impact on this place were excised.

The Greek Catholic Church was not only banned, but replaced with an official Soviet-state sponsored Russian Orthodox Church and the local population forcibly converted to the new faith. Moments in history when west Ukrainians sought to define themselves as separate from Russian influence were brought up as cautionary tales that had led Ukrainians to ally with Russia’s enemies—WWII as the most prominent example.

When the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 began, west Ukraine experienced yet another demographic shift.

According to the New York Times, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have passed through the city of L’viv alone and city officials expect at least 50,000 of these refugees to remain. With this influx, west Ukraine has still managed to serve as a hub for journalists reporting on the war, NGOs working to help those in need in Ukraine, and cultural institutions.

And so, yet again, west Ukraine has become home to a population with diverse places of origins and diverse experiences of the war. Yet unlike in the Soviet era, there is more freedom to grapple with what this diversity means now, and also what it meant historically.

The chance to build a new foundation for Ukraine that considered the complexities of Ukrainian history and the trauma of war eluded Ukrainians in the Soviet era—might it be possible today?