On October 1, 2017, the Spanish region of Catalonia—known as Catalunya to Catalonians—voted to declare itself an independent country from Spain, triggering confusion, fear, and demonstrations in the streets. Why did Catalonians vote to leave Spain and why is Spain so reluctant to let them go? These ten historical moments help us understand the long and complicated relationships Catalunya has had with Spain as well as with the international community.

1. The Nineteen Autonomous Regions of Spain

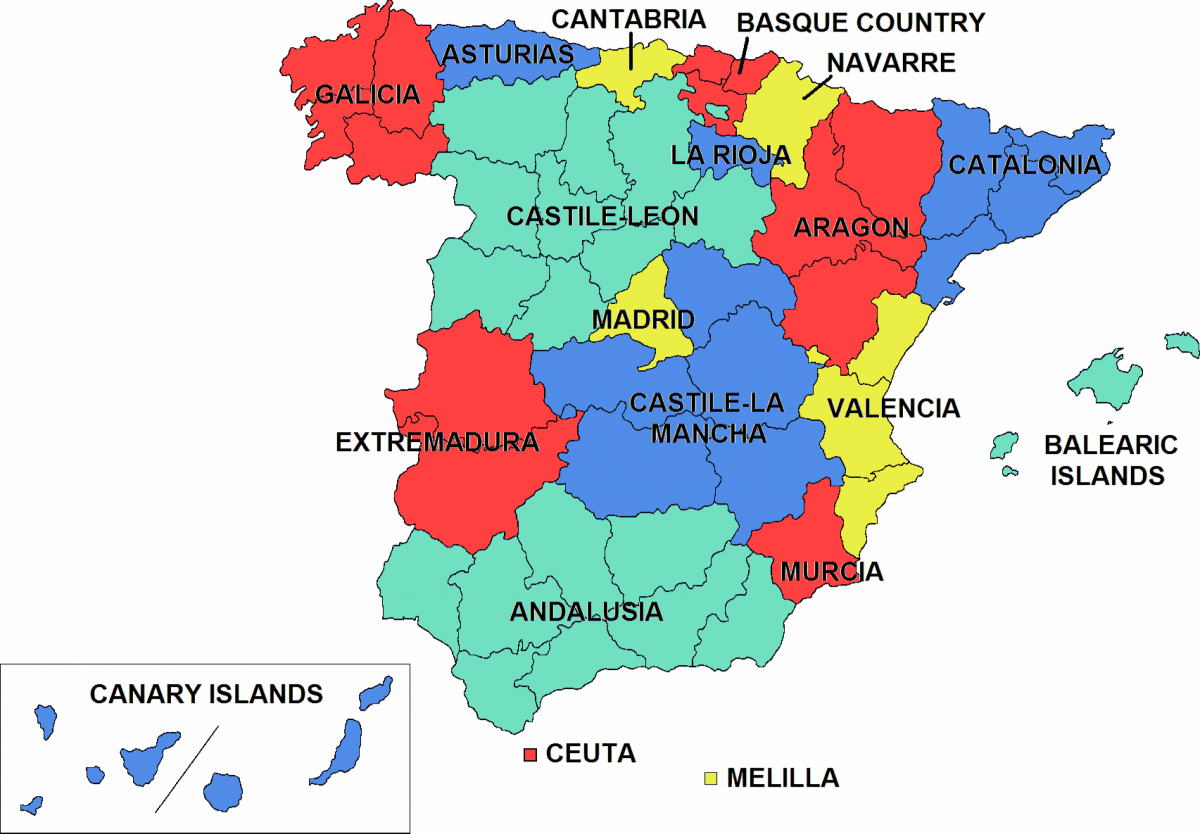

The autonomous regions of Spain.

Spain is made up of 19 autonomous regions/cities in the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, and the Atlantic Ocean. Each region governs itself, electing its own Parliament and running its own local government. Some governments have more autonomy but all have direct input on services within their region. Catalunya and the Basque country have their own independent police forces and the Basque Country and Navarra have independent fiscal systems and collect their own taxes, something for which other regions, such as Catalunya, have also asked. Catalans speak their own language which is related to Spanish and French, known as Catalan.

2. Catalunya: A Medieval Borderland

Miniature of Charlemagne and four Muslim commanders from the Talbot Shrewsbury Book, 1444-1445.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire and invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by the Visigoths in 460 CE, Catalunya, along with the majority of the Iberian Peninsula, experienced stability as part of the Visigoth Kingdom centered in Toledo (in present-day region Castile-La Mancha). In 718, Muslim invaders swept the peninsula, attacking cities in southern France. By 760, the Franks began pushing the Arab invaders back, maintaining the region as a buffer zone between the Franks and Muslims.

In 801, Louis the Pious, the son of the Frankish king Charlemagne, captured Barcelona from the Muslims. Catalunya became part of the Spanish Marches, borderlands where war-parties roamed, until Charles the Bald incorporated the region into a hereditary County, governed by the Counts of Barcelona. As the Frankish influence weakened, the counts grew in power, gradually taking control over all of Catalunya, as the region became called by about 1100.

3. Aragon and the Corts of Catalunya

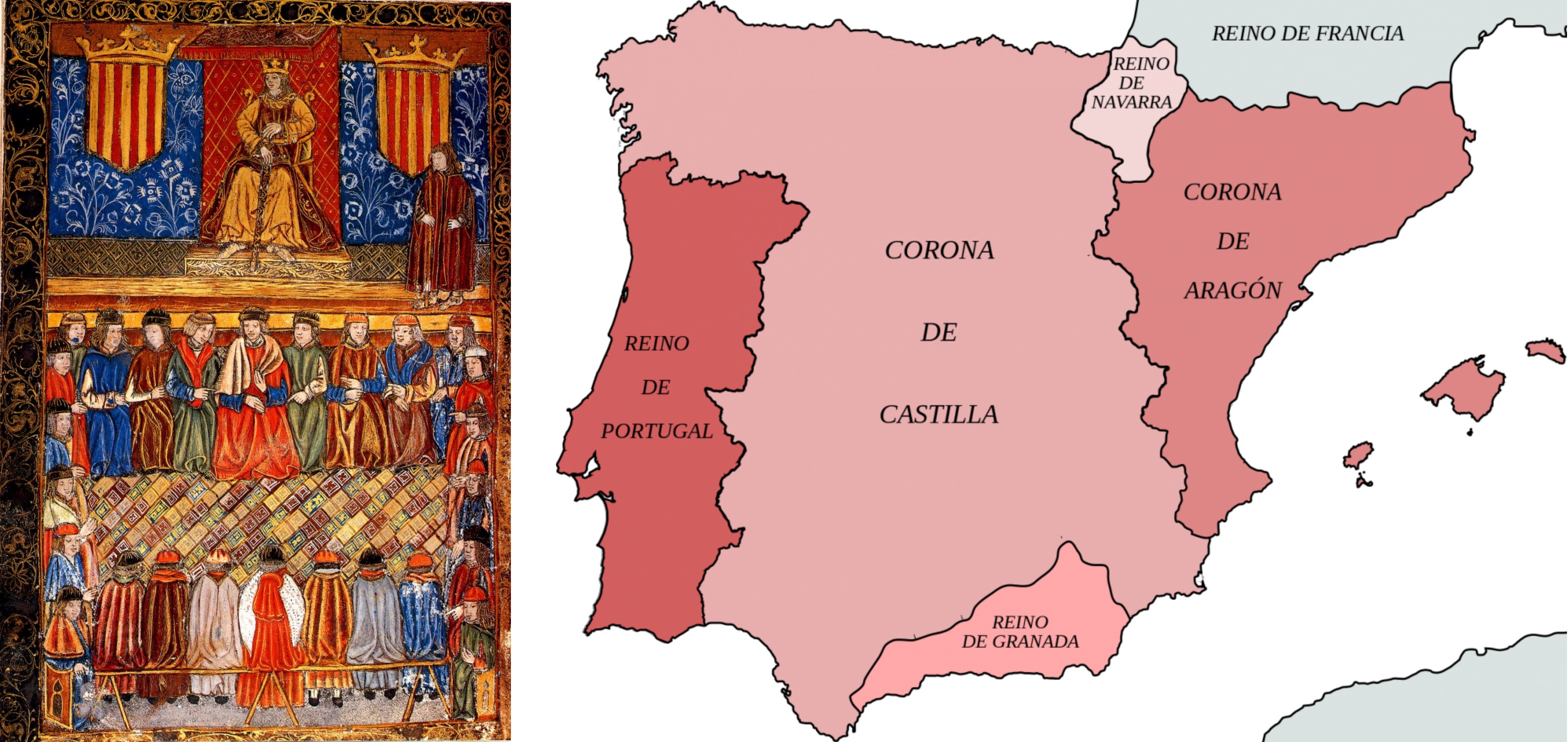

The Corts of Catalunya in the 14th century (left), and a map of the Iberian Kingdoms in 1400 (right).

In the 12th century, when one of the kings of Aragon decided to marry a princess of the House of Barcelona, Catalunya became integrated into the kingdom of Aragon. Aragon was already expanding, and soon claimed the small kingdoms of Valencia, a city-state south of Barcelona, as well as the island kingdoms of Majorca, Sardinia, Sicily, and Corsica in the Mediterranean. Rather than being subsumed into the kingdom of Aragon, Barcelona’s ideal position on the Mediterranean coast made it one of the most important cities in the kingdom.

The populace, already used to self-government after the loose control of the Franks, evolved one of the earliest parliamentary bodies in Europe, the corts of Catalunya, which wielded a great amount of power over the government. The corts were made up of three estates: the military, ecclesiastical, and royal estates, which all had input into governance. Although the king presided over the corts, by the 13th century they banned his power to create legislation unilaterally. The corts also had their own tax collection agent, known as the Generalitat, who maintained power over the enforcement of the law.

In 1469, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon married, both inheriting their fathers’ kingdoms upon their deaths. This union of the crowns brought Catalunya into a loose confederation of kingdoms ruled by the two monarchs, known as Spain. Although both claimed to rule jointly, the kingdoms remained separate jurisdictions, with Isabella governing the majority of the Iberian Peninsula, and Ferdinand governing Aragon. When Isabella accompanied her husband to Aragon and attended the Catalan corts, she was horrified to find that they contradicted him. She raged that she would have the members of the corts all beheaded, and Ferdinand quickly shuffled her away. She never again attended the corts.

4. The End of Catalan Autonomy and the Beginning of Resistance

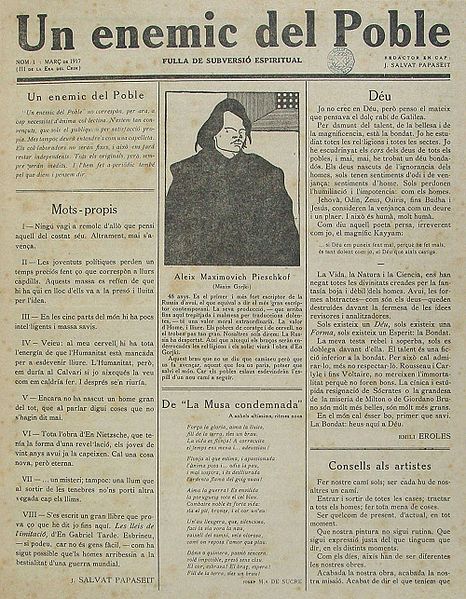

The first newspaper published in the Catalan language, Un Enemic del Poble, March 1917.

While Spain would not become a unified kingdom with one government until 1716, when a scion of the French house of Bourbon claimed the Spanish throne, the cortes faced increasing pressure from Ferdinand and Isabella’s heirs. They strove to lessen Catalunya’s individual power as Spain became more centralized. The Catalan Revolt of 1640-1652 was a response to Spanish abuse of power in the region.

After 1716, Catalunya became increasingly industrialized, which created clashes between the powers of the central government of Spain in Madrid and Catalan people who desired working-class rights and more autonomy for their regional government.

The 19th century saw a rebirth of the Catalan language (today spoken by 95% of the population of the region), known as the Renaixença, or Renaissance. At the same time, anarchist labor reformers in Catalunya achieved the first eight-hour work day in Europe in 1919. Both labor and culture movements signaled Catalunya’s trend of cultural and economic independence and progressivism, characteristics that define the region today.

5. Gaudí

A view looking up at the roof of the nave inside the Sagrada Familia.

Arguably Catalunya’s greatest and most well-known artist, the architect Antoni Gaudí i Cornet was born in 1852 in Barcelona. Heavily influenced by European Modernism, which rejected the elevation of classical art and architecture of the Enlightenment and the industrial shapes of the Industrial Revolution, Gaudí sought to return to the historical forms of the region, including Moorish and Gothic designs of the Middle Ages. He also wanted to reflect the beauty of the natural world, especially the Mediterranean seascapes and ocean waves of his home city, which undulate throughout his architecture. This tendency was heavily influenced by the Renaixença, which privileged Catalunya’s culture over all others.

Despite the emphasis on natural forms, Gaudí was a master at the technical. His masterpiece, the Basilica Sagrada Familia, remains unfinished after 135 years of construction, due in no small part to the fact that the advanced construction techniques needed to complete the enormous church (such as computer-aided design) would not be invented until the end of the 20th century. Gaudí died in 1927.

6. The Spanish Civil War and Authoritarianism

The Nationalists bombing Barcelona in 1938.

In the 1930s, Catalunya’s long bid for self-rule was reborn in the autonomous governing body of the Generalitat of Catalunya, which included a tri-cameral government. The first president, Francesc Macià, was left-wing and leaned towards independence from Spain. However, in 1936, when a group of military officers attempted to overthrow the left-wing Spanish government, the coup failed and the ensuing struggle boiled over into the Spanish Civil War.

In Catalunya, a coalition of pro-labor, anarchist, and communist factions joined to assert independent rule from Spain, keeping the Generalitat in control of the newly independent region. They set up the beginnings of a socialist-leaning regime that destroyed churches and emphasized the rights of workers to control the means of production. However, by 1938, disagreements among the groups running the new country destabilized Catalunya.

The divided government could not repel the attacks by Nationalist forces from Spain. By 1939, the remnants of the Catalan army retreated into France. The Nationalists under the control of fascist dictator Francisco Franco placed Catalunya under direct Spanish control from Madrid. Emphasizing a Madrid-centered Spanish nationalism, he outlawed Catalan customs and cultural dances, the Catalan language, and even made Catalans with Catalan names change them to the Spanish equivalent.

7. The Return of Catalunya

In 1975, Franco died, leaving King Juan Carlos as his successor. The King immediately ended Spain’s fascist state and instituted parliamentary and democratic rule, which emphasized regionalism and cultural plurality once again. Catalan autonomy was restored in 1979, and the Generalitat of Catalunya governed all domestic areas except education, healthcare, and justice, sharing that power with the central Spanish government. Catalunya also sought to create its own police force, rejecting the central government’s Civil Guard and National Police forces, which had inflicted great brutality on the Catalans during the Franco years.

Catalunya’s economy and international prestige grew at this time, resulting in their hosting the Olympics in 1992 in Barcelona, as well as a variety of other global meetings. In 2006, Catalunya passed another statute by popular referendum that granted it even greater self-rule and cultural differentiation from Spain, perhaps the most important of which had to do with finance. In 2010, following Spain’s slide into economic decline in the global recession, the conservative central government had the constitutional court overturn the statute of 2006, creating outrage amongst the populace.

8. Spain in the EU

In 1986 Spain and its autonomous regions became members of the European Union (EU), which granted them the benefits of their inclusion in the larger European Community and access to a joint currency, open borders among member states, the protection of a united military front, and an internal free market. While states are sovereign in the EU, all member states agree to support one another financially, politically, and militarily.

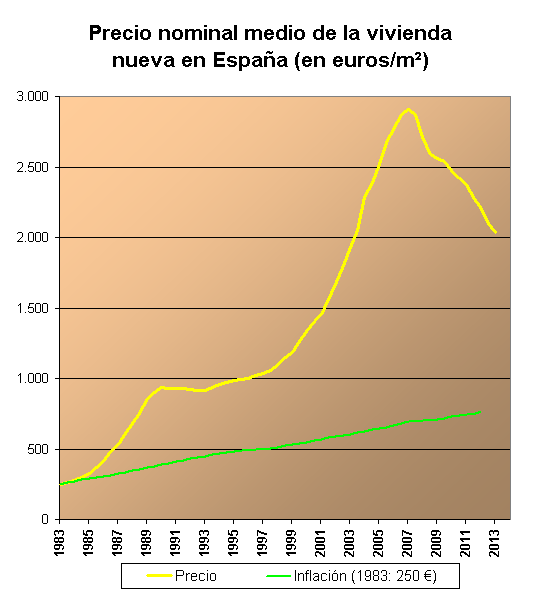

However, the EU became destabilized by the global financial market crash of 2008, when the economies of Spain and a number of other member states crashed due to the collapse of a housing bubble. Spain was unable to regain a command of the economy until 2012, requiring a bailout from the EU’s financial assistance program to member companies. The austerity program enacted to combat the crash affected Catalunya more than any of the other regions as they experienced the sharpest budget cuts.

9. Violence in the Streets

Nationalist police forces in Barcelona preventing voting in the October 1, 2017 referendum.

After the 2006 Statute of Autonomy was overturned by the Spanish courts in 2010, over 550 municipalities around the region of Catalunya held referendums for the independence of the region, with about 30% of the population voting, and a high percentage of votes for independence. In 2013 the parliament adopted a sovereignty clause, declaring that they had the right to decide if they wanted to be independent or not. Again in 2014, 42% percent of the population voted, with 81% of them in favor of Catalunya becoming an independent state within the EU.

In 2015 the parliament again announced plans to hold a (binding) resolution for independence. While the Spanish courts deemed this act illegal, the referendum was held on October 1, 2017, even though the Spanish government had ordered the police to confiscate ballots and close the polls. Spanish efforts to keep people from voting resulted in the heavily publicized and denounced violence of Spanish national police forces against voters in a few municipalities. This referendum showed a 90% vote in favor of declaring independence, with a turnout of 43%—although Catalan nationalists point to the closure of polls and the threat of police violence as a limiting factor in voter turnout.

10. Uncertainty about the Future

One of the proposed flags of an independent nation of Catalunya.

On October 27, 2017, Catalunya’s Assembly voted in favor of independence, without any support from the EU, other international allies, or the Spanish government. The Spanish Senate immediately invoked their constitutional right to seize a rebelling region and impose central rule, dissolving the Catalan parliament and dismissing the rest of their government.

As of November 18, 2017, the regional government leaders have fled into EU custody and will likely stand trial in Madrid for rebellion. Demonstrators have participated in a general strike. Meanwhile there is growing concern that economic interests will not remain in an independent Catalunya, given the EU’s rejection of their movement. At this time, there is an election planned by the central Spanish government to create a new regional government in Catalunya on December 21, 2017. There is no clear outcome to these elections, and the region remains caught between independence and centralization.