Forty years ago on January 27, 1973, the U.S. War in Viet Nam officially concluded with the signing of the Paris Peace Accord. It was then the longest war in U.S. history; although commonly dated as beginning in 1965 with American bombing and ground-troop campaigns, U.S. involvement in Viet Nam actually extended back to the end of World War II.

In the aftermath of this global war, the Vietnamese under Ho Chi Minh sought political independence from the French, fighting the First Indochinese War. During this nine-year conflict, the U.S. supported France’s campaign to recolonize Viet Nam and towards the end was financing 80% of the military costs of this losing effort.

The Vietnamese victory on the battlefield was tempered by the 1954 Geneva Accords, which mandated a temporary division of the country at the 17th parallel but promised national elections within two years’ time. Determined to prevent reunification of Vietnam under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, the likely victor of national elections, the U.S. supported a series of anti-communist and dictatorial political leaders who formed the Republic of Viet Nam in the South. This financial and military commitment led to covert as well as overt conflicts against the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam in the North and the National Liberation Front in the South. The Vietnamese call it the U.S. War in Viet Nam or the Second Indochinese War; Americans call it the Viet Nam War.

By any name it was particularly brutal. As Peter Arnett reported in the New York Times in 1968, an unidentified U.S. military officer explained a military attack on a Vietnamese village by saying, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” The quote encapsulates the tragic irony of U.S. strategy in South Viet Nam. In order to save the country from communism, American politicians and the military destroyed the land and its people.

In total, U.S. pilots dropped more than three times the tonnage of bombs on Viet Nam as it dropped anywhere during World War II. In fact, twice as many bombs rained down in the South, America’s ally, as in the North, the designated enemy.

The bombs were not just intended to destroy military targets, which include military sites or the manufacturing, transportation, and communication infrastructure. Despite U.S. government denials, eye-witness accounts by American travelers and international journalists indicate that residential areas, schools, hospitals, and dikes that could cause flooding and widespread famine were bombed repeatedly. In addition, the U.S. military used cluster bombs, which maximized human injury through the explosive dispersal of tiny bomb fragments that made detection and extraction difficult.

Americans also deployed chemical warfare, using Agent Orange and napalm to defoliate forests and burn down villages. These biological weapons have had long-lasting effects on both the ecology and people of Viet Nam.

Seeking to contain the National Liberation Front and its supporters, the U.S. military and the South Vietnamese government designated certain villages and its surrounding countryside as “free fire zones.” Any person living or working in these areas was considered a likely enemy. As Mary Hershberger writes in Traveling to Vietnam: American Peace Activists and the War: villagers were rounded up into “‘strategic hamlets,’ which the Vietnamese called concentration camps. These hamlets were surrounded by barbed wire and required passes for those leaving and entering.”

An estimated 4 million people, about a quarter of the South Vietnamese population, became refugees by the end of the war, according to Mark Philip Bradley in Vietnam at War. Those who did not evacuate targeted areas and even those who did relocate, including the very young, the elderly, and women, were at times tortured, brutalized, and killed by American soldiers in search-and-destroy missions.

The total number of Americans who died or are missing in the war is just over 58,000, while estimates of the number of Vietnamese who died range from 2.1 million to 3.8 million.

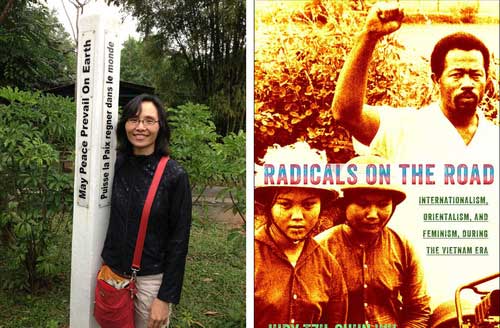

These facts about the Viet Nam War only emerged over time as American citizens began to question how their government and mainstream media sources represented the meaning and conduct of the war. I recently completed a book, Radicals on the Road, that examines how skeptics of the U.S. government traveled to Viet Nam to witness the conditions of war and to dialogue with the designated enemies of their country. Some of these travelers were already antiwar activists, while others dedicated themselves to promoting peace as the result of their journeys.

When I learned that a group of American activists, all of whom had visited North or South Viet Nam during the war, were returning to Viet Nam for the 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords, I jumped at the chance to accompany them. I had researched and interviewed some of them for my book, and I was eager to meet them again as well as others unknown to me. Our encounters with Viet Nam in 2013 inspired reflections on the legacies of the U.S. War in Viet Nam and the antiwar movement.

My fellow travelers (pictured above) began calling themselves the Hanoi 9 as a humorous tribute to how political dissidents during the 1960s became identified by the place of their activities and the number of people charged with various crimes by the government for protesting. The co-leaders and organizers were Karin Aguilar-San Juan (an Associate Professor of American Studies at Macalester College who invited me to join the delegation), Frank Joyce (a Detroit-based labor and anti-racism activist) and John McAuliff (who first arrived in Viet Nam with the Quakers). John has deep connections with non-government organizations (NGOs) working in Viet Nam, although John himself has been more engaged in fostering ties with Cuba in more recent years.

Other travelers included Chicago 7 defendant and Students for a Democratic Society co-founder Rennie Davis; Youth International Party (YIPPIE) organizers, Judy Gumbo Albert and Nancy Kurshan (Nancy would later become a member of the Weathermen who adopted some of the guerilla tactics of the NLF to stop American militarism); as well as Jay Craven, Becca Wilson, and Doug Hostetter, who traveled to North Vietnam as part of the U.S. National Student Association delegation that initiated the 1970 Peoples Peace Treaty. Craven, Davis, Hostetter, McAuliff, and Albert also helped lead the 1971 May Day demonstrations—widespread acts of nonviolent civil disobedience in Washington, D.C. that resulted in the largest mass arrest in U.S. history.

Of the Hanoi 9, I had the longest connection to Alex Hing (pictured here with a former Tiger Cage prisoner), a Chinese American activist whom I had previously interviewed about his travels to socialist Asia with Eldridge Cleaver. Hing was the former Minister of Education for the Red Guards, U.S.A., a San Francisco Chinatown-based youth organization inspired by the Black Panther Party and by Asian countries seeking independence from colonialism. As a person of color, Hing understood his antiwar activism as an integral part of a movement against racism in the U.S. and globally.

I met Doug Hostetter for the first time on this trip and was deeply impressed by him. (He provided these photos of himself with a Vietnamese friend and of a Vietnamese peasant farmer’s wedding.) Hostetter was a conscientious objector who did alternative service in Viet Nam as a Mennonite volunteer. Based in a village in the South, Hostetter worked with Vietnamese high school students to help provide education for the younger children in that area and to improve literacy.

As one of only a few Americans in the village, Hostetter experienced life on the front lines of a guerilla-style war. During the day, the Republic of Viet Nam military and government personnel were in control. However, every once in a while at night, the NLF moved in and asserted their dominance. Hostetter recalled hearing gunfire exchanges during those evenings and the door-to-door sweeps as the NLF searched for political collaborators. He was spared because locals vouched for his good work.

Even as a committed Pacifist, he respected the NLF for targeting corrupt officials, some of whom were embezzling educational funds. But he witnessed the disproportionate response of the South Vietnamese government and American allies who directed intimidation, torture, and violence towards anyone likely to support the NLF.

Clearly, Viet Nam had profoundly shaped the identities and political convictions of the Hanoi 9. Jay Craven, formerly a student body president at Boston University and a mentee of pacifist Dave Dellinger and historian Howard Zinn, recalled that he learned math by memorizing and recounting American bombing statistics. He also became a filmmaker and arts activist. Through the antiwar movement, Craven learned about the power of culture in creating community and fostering political consciousness.

Similarly, Judy Gumbo Albert (pictured here with me at a banquet) recalled that she wanted to emulate the Viet Cong by being the Americong. She demonstrated her commitment to this political lifestyle when we visited the tunnels of Cu Chi. This was an extensive network of underground pathways that the NLF dug to hide and conduct war. Some of the spaces have been enlarged to allow tourists to briefly experience the claustrophobic conditions endured by NLF guerilla fighters for years. Albert readily crawled into a small hole that had not been enlarged.

The profound connection of activists like Craven and Albert to Viet Nam crystallized for me when we visited the Thien Mu (Heavenly Lady) Pagoda in Hue. This was the home of Thich Quang Duc, the Buddhist monk who burned himself alive in 1963 to protest the South Vietnamese government’s political repression of Buddhism. The pagoda still hosts an active community of monks, who were chanting and performing a ceremony when we arrived.

Albert, who had been mourning the loss of her long-time partner, Stew Albert, decided to observe the anniversary of his death at the Pagoda, delivering a funny yet moving tribute to Stew in the spirit of the Yippies. Others joined in, some of whom knew Stew personally or wanted to honor his legacy as a counter-cultural figure. Craven decided to recognize the passing of Dellinger and Zinn at the temple as well. This moment illustrated the profound resonance between American and Vietnamese sacrifices for peace and freedom.

Our travels to Viet Nam were not just occupied by personal and informal expressions of international solidarity. The 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accord was also the occasion for formal celebrations by the Vietnamese.

I had written about how delegations of American antiwar activists during the war had been treated as dignitaries, but I was still unprepared for our red-carpet treatment. We attended VIP government and media commemorations and were treated to elaborate multi-course banquets for almost every meal. One of the Hanoi 9 pointed out the irony that they were unlikely to ever receive the same type of respect and courtesy from their own government.

The Vietnamese expressed deep gratitude not only to American antiwar activists but also to representatives from a variety of countries who helped end the war. Special guests from Egypt, the former Soviet Union, China, Venezuela, Italy, and France attended these commemorations.

André Menras, a Frenchmen imprisoned by the Saigon government for two and a half years for waving the NLF flag, told a moving story. While in prison, he learned Vietnamese and helped organize against political repression. When he was released, partly due to diplomatic pressure as a result of the Paris peace talks, Menras publicized a list of political prisoners who were being tortured in South Vietnamese jails. At the time, the Republic of Viet Nam government denied having any political prisoners.

Our delegation also met with a group of Vietnamese who were former political prisoners. Some had been incarcerated for 10 years in places like Con Son Island, a former French penal colony that became a site of imprisonment and torture under the Republic of Viet Nam. After the Paris Peace Accords, which the South Vietnamese government grudgingly signed, the political prisoners in places like Con Son were re-categorized as criminals to prevent their release.

The individuals who spoke to our delegation recalled protesting this reprocessing. They moistened their hands and rubbed out their fingerprints on rough surfaces; they resisted being carried out of their cramped prison cells (a 100-cubic-meter room held 190 prisoners)—prison guards had to gas the rooms before transporting the prisoners’ bodies out; and the prisoners also opened their mouths as wide as possible to prevent accurate mug shots. Even with these efforts, the prisoners on Con Son were not released until after April 30, 1975, the fall of Saigon.

At the center of the Paris Peace Accord commemorations was Madame Nguyen Thi Binh, the former foreign minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (the political wing of the NLF). She was the PRG’s primary representative at the Paris Peace Talks. I had written about Binh in my book, because she played such a central role in communicating with peace advocates in the West, particularly among women’s groups.

Binh was such an important figure that her image appeared on t-shirts worn by American women’s liberation activists, making Binh, in my mind, a Vietnamese female equivalent to Che Guevara. During this trip, I learned that there was even an American protest song about Binh, entitled “Live Like Her, Madame Binh.”

During my first trip to Viet Nam a few years ago, I had hoped to meet and interview her. Much to my disappointment, she could not accommodate my request. However, during this trip, Madame Binh gave a special dinner for some members of the Hanoi 9, almost all of whom had met with her in France. The representatives of the PRG and the DRV in Paris were not just state-to-state diplomats. They also practiced people’s diplomacy and treated antiwar activists as significant political players.

The 40th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accord provided an opportunity to not only recognize the past but also assess the ongoing legacies of the U.S. War in Viet Nam. The anniversary passed with relatively little notice in the U.S. Even after American officials signed the Paris Peace Accord, presidents Nixon and Ford continued to supply financial and military support to the Republic of Viet Nam until Congress finally cut off funding. Even today, Vietnam is a psychological and emotional wound for many Americans, who resent “losing” the war.

“Winning” the war, however, also generates bittersweet emotions. Our delegation visited schools and met children, some of whom are three or four generations removed from the war, but still suffer physical and mental disabilities from Agent Orange.

In one school, the students gave us a rousing dance rendition of “Gangnam Style,” a South Korean rap hit that my 9-year-old son in Columbus, Ohio sings. Our delegation responded by performing the civil rights song “We Shall Overcome,” and “Ho-Ho-Ho Chi Minh,” an American protest song.

The kids were excited and happy about our visit, but I felt a deep sense of pain and guilt. I was only born in 1968 (the year of the Tet Offensive and the protests at the Democratic Convention in Chicago) and immigrated to the U.S. in 1975 from Taiwan (the year that Viet Nam was reunified). However, I realized that these kids would not be in a “special” school for children with disabilities if the U.S. had not used Agent Orange.

In addition to this afterlife of Agent Orange, there are unexploded ordnances embedded in the landscape of Viet Nam. These bombs and mines continue to be detonated accidentally, sometimes resulting in dismemberment or death. We visited an NGO called Peace Trees, which is trying to refoliate parts of Viet Nam and teaching Vietnamese children to recognize and stay away from dangerous objects and potential ordnances. When we visited a U.S. government-funded Agent Orange cleanup site in Danang, our American guides, some of them veterans of the Viet Nam War, warned us to stay on well-trodden paths since recent rains might resurface unexploded ordnances.

For a long time, the U.S. government resisted responsibility in helping to reconstruct Viet Nam, a land it had bombed and poisoned in the name of democracy. This contrasts with the billions spent to rebuild Europe, Japan, and South Korea. Only in 1995, twenty years after the reunification of Viet Nam, did the U.S. normalize political and trade relations with its former enemy. However, the lack of public recognition of the Paris Peace Accords in the U.S. and the continuing bitterness about the Viet Nam War among many Americans suggests an ongoing cultural and emotional embargo.

Viet Nam is far from a perfect country, although it was once idealized as the ultimate underdog against the American Goliath by many peace activists around the world. While acknowledging the imperfections of the Vietnamese government and society, former antiwar activists, like Doug Hostetter, nevertheless feel a sense of responsibility to help rectify what the U.S. has done.

This commitment to the people of Viet Nam and this desire to right wrongs exemplify the spirit of the American antiwar movement during the war. The fact that the Hanoi 9, all of whom are involved in political activism in some form today, continue to feel this connection and responsibility suggests that the internationalism of the 1960s and 1970s has the potential to revive and persist into the 21st century.

[My profound thanks to the Vietnam-U.S.A. Society who hosted our delegation, the Hanoi 9, and the remaining members of our delegation: Karin Aguilar-San Juan who is writing a book about Susan Sontag’s travels in Viet Nam; labor activist and delegation comedian Mary Anne Bennett; videographer Amanda Wilder; as well as patient and supportive partners Steve Whitman and Kirsten Liegmann. — Judy Tzu-Chun Wu]