When Ukrainian troops liberated the town of Borodyanka from Russian occupation in early April, 2022 they discovered the damage done to its Taras Shevchenko monument. Bullets had hit the great poet’s forehead. The pillar holding him up had been damaged by shells.

The symbolism of the Russian attack on the monument was obvious. Taras Shevchenko is not just the founder of the modern Ukrainian literary language, he is also the most important symbol of modern Ukrainian nationhood.

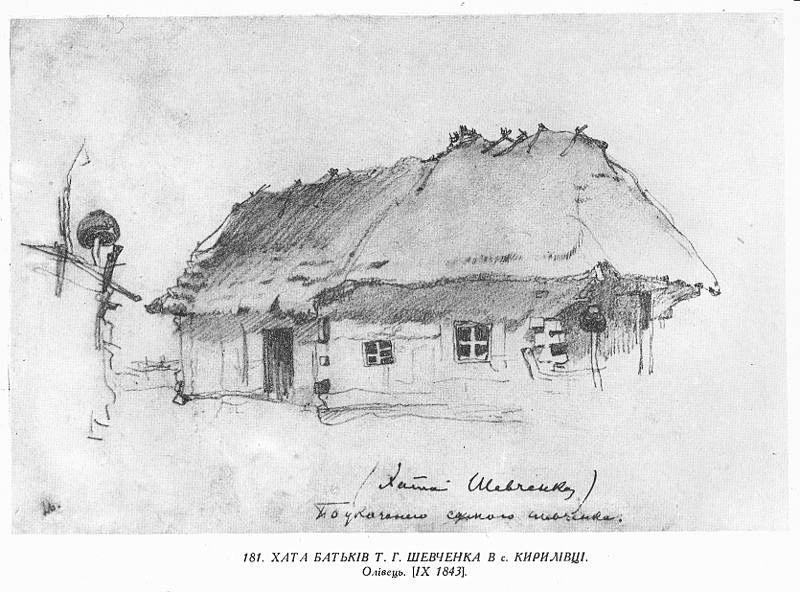

Born a serf in March 1814 on an estate just over 100 miles from Kyiv, Shevchenko demonstrated an early aptitude for art. When his owner moved to St. Petersburg in 1831, he took Taras with him. Shevchenko started to paint and write: recognizing his talents, a handful of prominent Russian and Ukrainian artists purchased his freedom.

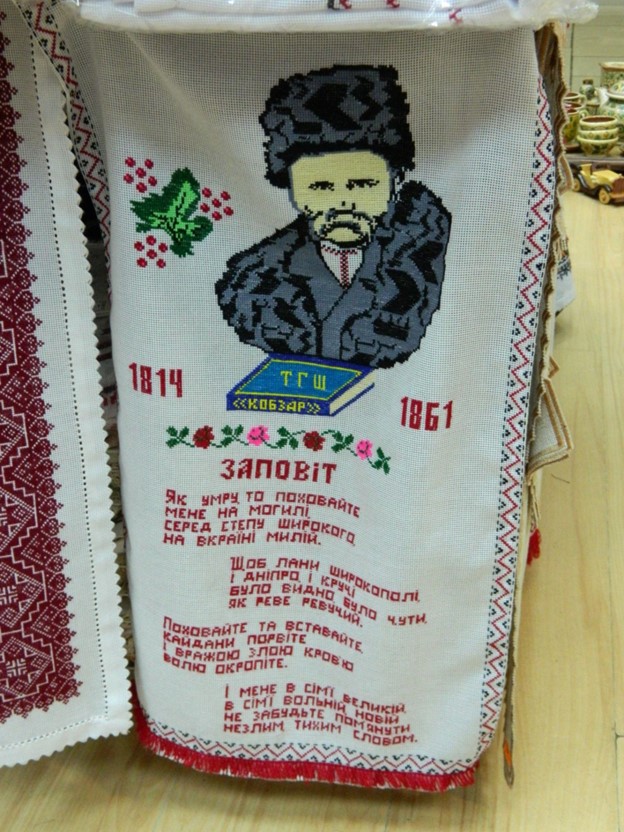

Liberated from bondage, Shevchenko turned to poetry. In 1840, he published his first collection, Kobzar, named after the bards who sang tales on their stringed instrument, the kobza. Shevchenko’s poems imagined Ukraine as a distinct nation with a people, culture, and history separate from Russia.

Inspired by his reading of romantic histories, Shevchenko’s Kobzar appropriated the history of the Cossacks for Ukraine. The freedom they embodied became a potent inspiration for Ukrainian readers. His 1838 poem “Night of Taras,” for example, about a 1630 peasant revolt, included these lines:

Ukraine, O my dear Ukraine,

Trampled by the Polacks!

My dearest!

When I think of you, my homeland,

My heart can only cry …

Whither all the Cossacks

Whither their red coats?

Whither our good fortune

And whither blessed freedom?

Shevchenko would also contrast Ukrainians with Russians. “Kateryna,” one of his most beloved poems, tells the tragic tale of a Ukrainian village girl seduced and then betrayed by a Russian soldier. It warns from the first lines, “Fall in love, you dark-browed girls, But not with Muscovites. For Muscovites are strangers, They will do you wrong.”

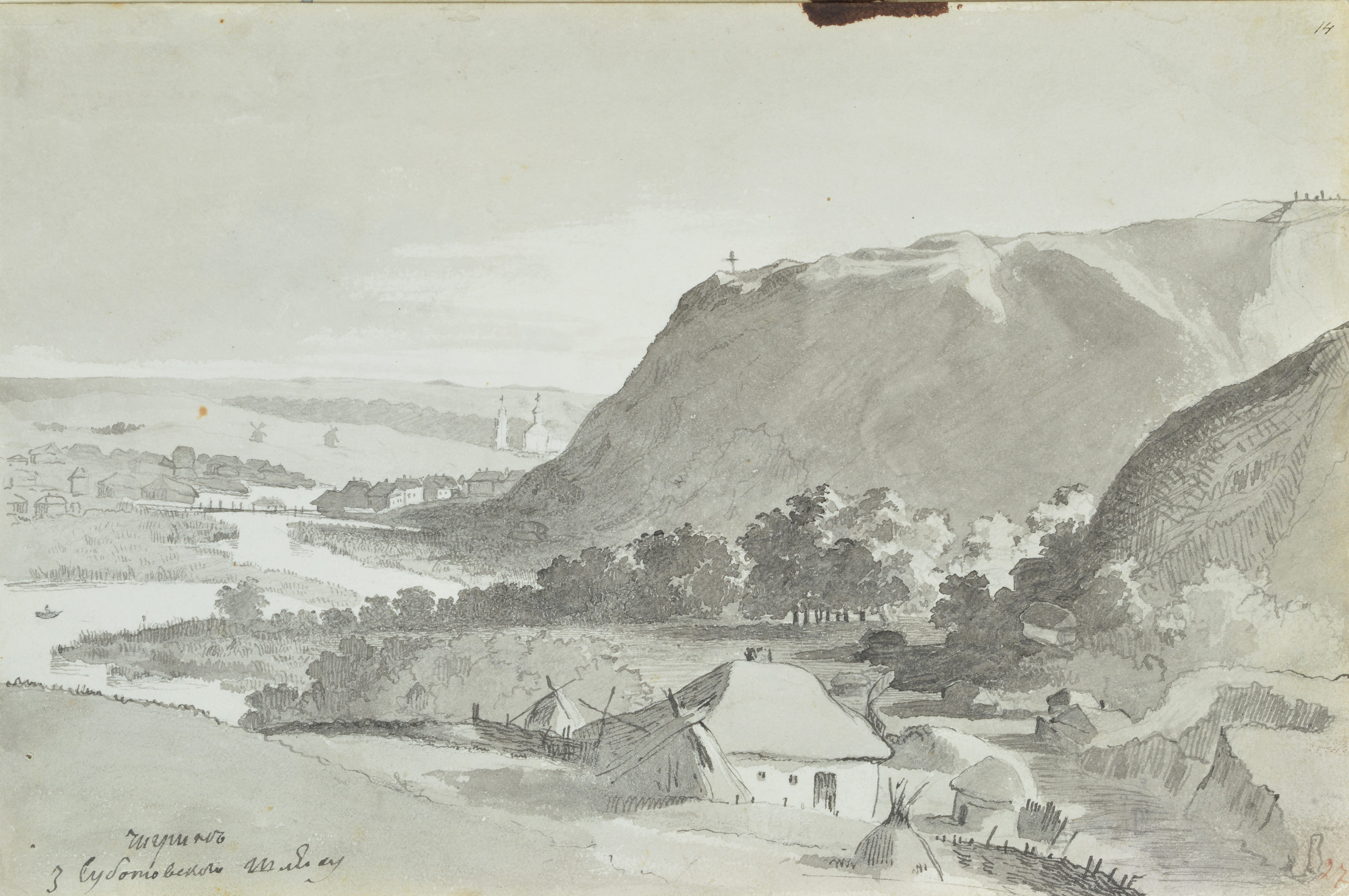

Kobzar brought Shevchenko acclaim. It also led to trouble. Traveling back to the Ukrainian lands, he lamented the lack of freedom among members of his family and members of his nation. He painted Ukrainian national landscapes and historical sites in an album he titled Picturesque Ukraine. He also befriended members of a secret society devoted to the right of Slavic peoples, including Ukrainians, to be independent.

Arrested in 1847, Tsar Nicholas I exiled the poet to an army post on the steppe frontier. The tsar also forbade Shevchenko from writing or painting. Freed from his imprisonment only in 1857, Shevchenko remained exiled from his beloved Ukraine. He never returned. He died in St. Petersburg one week before Tsar Alexander II announced the emancipation of the serfs in 1861.

In “Testament” (1845), Shevchenko asked “When I die, bury me in my own beloved Ukraine.” The poem also spoke to the mixing of his personal and political aims: “Oh bury me, then rise ye up, And break your heavy chains, And water with the tyrants' blood, The freedom you have gained.”

Shevchenko’s words, written in the Ukrainian language, remained a threat to the tsarist government. In 1863, the Interior Minister prohibited most forms of publication in the language, which Russian authorities termed “Little Russian.” Thirteen years later, Tsar Alexander II extended this ban to include all publications in Ukrainian.

Yet Shevchenko’s significance lived on. An 1894 biography published in Russian acknowledged that his muse was Ukraine because there he could soak up “his native atmosphere, his native natural landscape, his native people.” His poems continued to circulate and crossed imperial borders to inspire Ukrainians living in Habsburg lands.

After the revolutions and civil war that briefly led to the first-ever independent Ukraine, the Soviet state tried to co-opt the idea and legacy of Shevchenko. Because of his background, Shevchenko could be rebranded as a revolutionary who had fought oppression for his people and for others. “The Bard of the Ukrainian People,” as one 1939 newspaper article declared, was a “great patriot and poet of the friendship of peoples.”

Statues of Shevchenko were built in the Soviet era, including the well-known one in the center of Kyiv and the one in nearby Borodyanka. Soviet authorities heralded Shevchenko as “the great son of Ukraine” (as an article from 1984 declared him), but he also remained a potent symbol for an independent Ukraine, his poems a reminder of its essential characteristics. When Ukraine gained independence in 1991, Shevchenko served as its spiritual founding father.

Back in Borodyanka this past April, Yaroslav Halubchik, an artist from nearby Kyiv, saw the damaged statue and immediately launched an art project. He called it “The Healing of Shevchenko.” Halubchik wrapped a bandage around the poet’s wounds.

Former Ukrainian minister of culture turned soldier Yevhen Nyshchuk happened to witness the bandaging and proclaimed: “This is really important, because we all know that Shevchenko and other Ukrainian poets were always enemies of Russia. I really hope that people will rebuild everything here as it was, but we should keep this as it is now.”

![]()

Learn More:

The Complete Kobzar: The Poetry of Taras Shevchenko. Translated by Peter Fedynsky. London: Glagoslav Publications, 2013.

Rory Finnin, “Nationalism and the Lyric, Or How Taras Shevchenko Speaks to Compatriots Dead, Living, and Unborn,” The Slavonic and East European Review 89/1 (2011): 29-55.

George G. Grabowicz, “Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet,” Revue des études slaves LXXXV-3 (2014): 421-439.

Boris Khersonsky, “Every Hut in Our Beloved Country is on the Edge.” Translated by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk. Literary Hub 11 March 2022.

Stephen M. Norris, “Shevchenko’s ‘Kobzar’ Portrays Ukrainian Nationhood.” Moscow Times 16 March 2014.