Sixty years ago this May, the U.S. Border Patrol enacted “Operation Wetback,” a campaign to deport Mexican workers who were in the country illegally. The program succeeded in rounding up over 1 million people, most of them men. Just two years before Operation Wetback, the Border Patrol had deported half as many people. This new policy marked the beginning of modern deportation raids and the militarization of the border that we are familiar with today.

The U.S. Border Patrol (pictured above in 1924 when it was officially created) carried out Operation Wetback to respond to the unintended consequences of another American policy, the Emergency Farm Labor Program. During World War II, when the U.S. economy faced an acute labor shortage, the U.S. and Mexico established a binational agreement to import temporary workers to harvest American crops and maintain and repair American railroads.

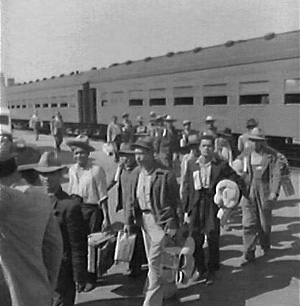

Though the agreement was initially supposed to relieve the wartime labor shortage, American farmers developed a penchant for imported farm workers and had the program renewed repeatedly for 22 years. Between 1942 and 1964 the Bracero Program, as it was popularly known, brought over 4 million Mexican men to the U.S. through renewable six month contracts (pictured to the right ca. 1942).

The program intentionally recruited only men as a way to safeguard against their permanent settlement in the U.S. They believed men would return to Mexico to be with their families. Yet some women also came in search of employment as did many men who were not able to secure Bracero contracts. The program thus inadvertently led to the dramatic increase of “illegal” Mexican immigration, as many migrants discovered that U.S. employers had a strong demand for Mexican labor and many would hire them with or without legal work permits.

During these years, the nation lived uneasily with the contradictions of its immigration policy and labor needs. The Bracero Program revealed American employers’ desire and demand for low-wage immigrant labor but less interest in actual immigrants who might settle and become part of the citizenry.

The program thus conditioned Mexican migrants (both Braceros and unauthorized immigrants) to work for temporary periods of time in the U.S. and then return home to family. In fact, this was the pattern of many Mexican immigrants for numerous years.

Our enforcement policy, however, had to reconcile the high demand for the importation of hundreds of thousands of workers but also the deportation of those who came without contracts.

Deportations inflamed tensions between agribusiness and federal authorities (and which both are still trying to work out). Large agricultural companies wanted cheap labor while the Border Patrol and Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) felt compelled to respond to Americans’ growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the early 1950s by tightening their control of the border.

For years before Operation Wetback, agribusiness used its economic prowess to control the U.S. Border Patrol’s enforcement of federal immigration law. On some occasions, Border Patrol and INS officials would simply look the other way when they encountered undocumented immigrants or, in some cases, legalize them on the spot to avoid disrupting an employers’ workforce, especially during peak harvest seasons.

Operation Wetback was supposed to mark a shift in these power dynamics by diminishing agribusiness’s control and asserting federal authority. The tension between employers looking for cheap labor and the federal government enforcing immigration laws remains today.

U.S. employers’ demand for low-wage immigrant labor is undeniable. Especially in agriculture, food processing, construction, and service industries, immigrants continue to do the lowest paid, least prestigious work that they have long done.

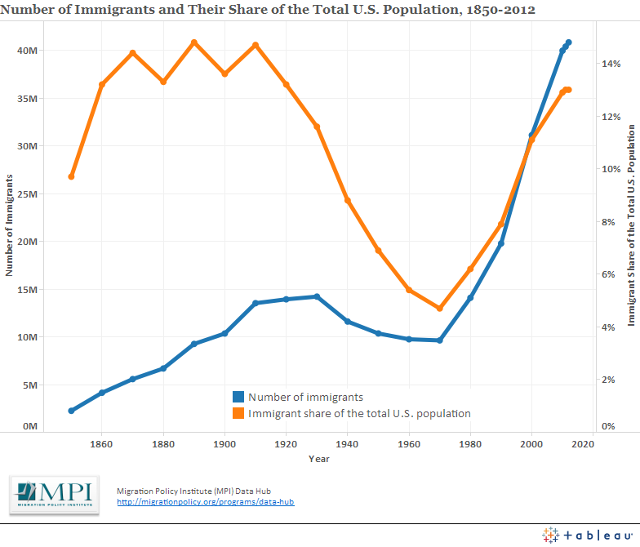

The restrictive immigration policies that prohibit so many of them from entering the country legally, however, have resulted in an estimated 11.5 million people living in the U.S. without authorization. The accompanying aggressive deportation policies of recent administrations have meant that such people are living very tenuously here in the U.S. with the constant threat of being removed and separated from their families.

During his 2012 campaign, President Obama promised that his administration would focus on deporting “criminals, gang bangers, [and] people who are hurting the community” rather than hard-working people who are contributing members of their communities. Yet the president, or “Deporter-in-Chief” as immigration activists have called him, has overseen the deportation of over 2 million people during his tenure—more than any of his predecessors or in any other period in U.S. history. Two-thirds of those deported have no criminal record, other than the civil violation of being undocumented.

Though in the current immigration debate Democrats have been more apt to propose immigration reform than their Republican counterparts, both parties might want to consider Governor Jeb Bush’s recent remarks on the personal, very human roots of illegal immigration. In April 2014 he contended that people living in the U.S. without documentation have come because they “worried that their children didn’t have food on the table.” He even went so far as to assert that immigration is “an act of love.”

Certainly, migration has been a survival strategy throughout human history. Regardless of one’s views on the matter, we would be wise to recognize that the current crisis has its historical origins decades earlier. Though immigration reform is unlikely in this midterm election year, politicians will want to take a more comprehensive historical view of our nation’s immigration and deportation policy.