On June 26, 1945, the San Francisco Conference concluded with the signing of the United Nations Charter. Over the previous two months, delegates from 50 nations who had opposed the Axis powers in World War II discussed how to create a new international organization dedicated to collective security and the goal that “all worthy human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people.”

The United Nations (UN) became an important forum for preserving peace, as well as debating and advancing cultural and political initiatives—most notably articulating and legitimizing the idea of human rights.

This change reflected a new bipartisan consensus that the United States should join and guide a new set of international institutions. U.S. participation was vital to this project because no international organization could function well without the world’s fastest rising power.

Though the organization was truly global, its creation was also proof that the United States was taking a more active role in world affairs. The San Francisco Conference gave the country the opportunity to fill the position it ignored a generation earlier when politicians had rejected participation in the League of Nations.

A generation earlier Woodrow Wilson helped create the League of Nations at the Versailles Conference at the end of World War I. The Senate, however, rejected the resulting treaty along party lines. The United States withdrew into what a hobbled Wilson bitterly called “a sullen and selfish isolation,” becoming an observer in the League but never a full member.

As Europe moved toward another war in the 1930s, the League proved unable to respond effectively. The United States remained on the sidelines as popular opinion largely ran against joining another European war until the shock of Pearl Harbor made inaction impossible.

During the war, President Franklin Roosevelt initially imagined a postwar order based around four policemen with regional authority (the Big Four: the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China). His staff and American allies gradually encouraged a drift toward a more inclusive cooperative body that began to cohere in the international summits that occurred with increasing regularity from 1943 onward.

Largely unified behind the war effort, Republicans encouraged this shift. Led by the New Deal critic and reformed Isolationist Arthur Vandenberg, the party committed to supporting a postwar cooperative peace organization before the 1944 election. A bipartisan push for U.S. international leadership was beginning to form with ambitions to shape the postwar world.

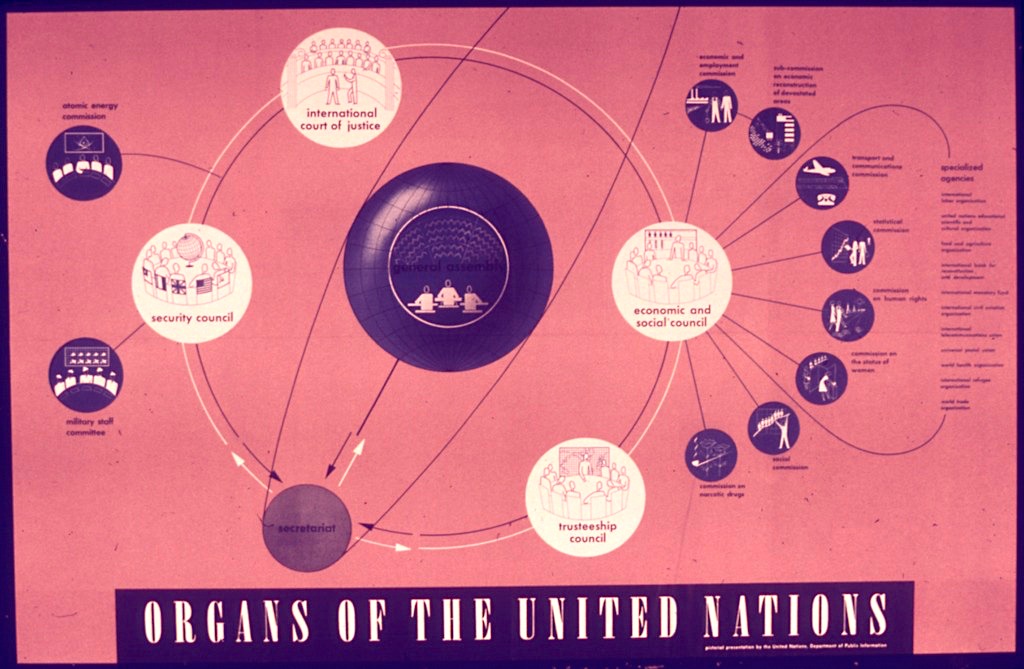

At the Dumbarton Oaks Conference held in the fall of 1944, representatives from the Big Four hashed out an outline of a broad organization open to all countries and concerned with security, economic, and social issues. Yet a number of matters remained unresolved, not least of which whether the Big Four would wield absolute vetoes as permanent members of the body’s security council.

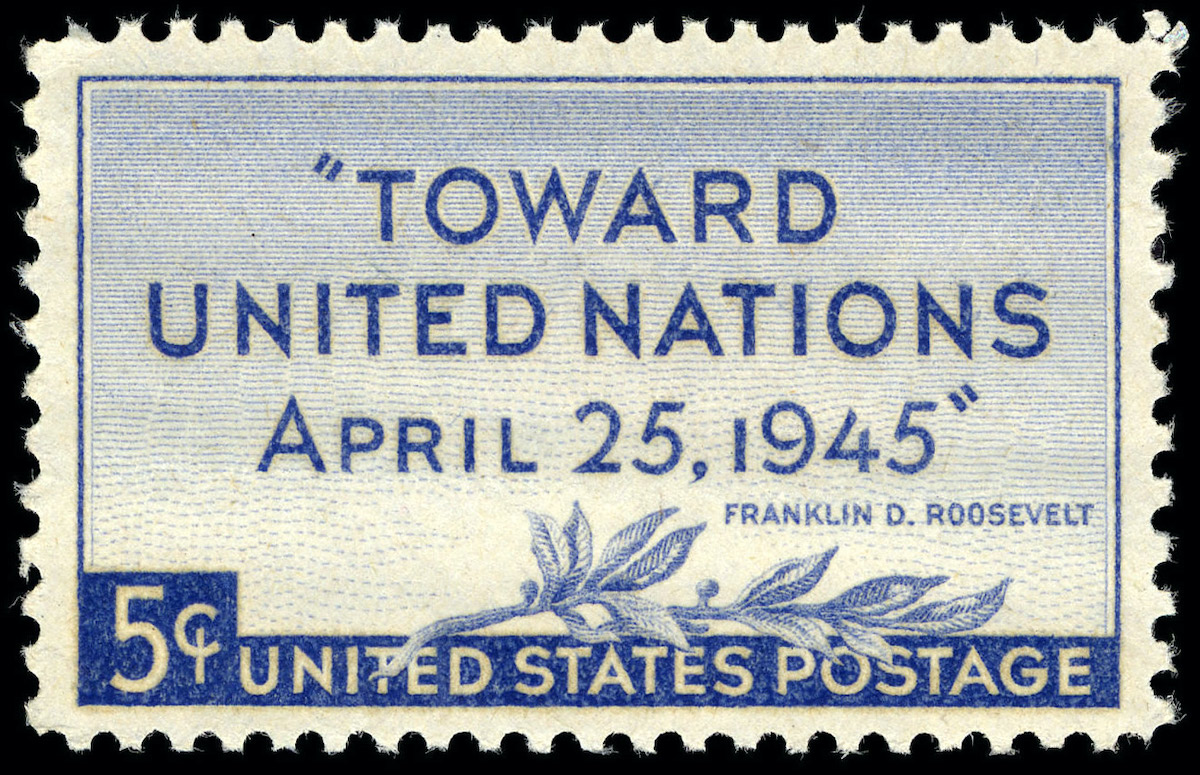

FDR recognized that the final negotiations in San Francisco would be contentious, and he would need Senate approval when they concluded. He appointed a delegation whose membership was half Republican, including Vandenberg and the future secretary of state John Foster Dulles. Leading this bipartisan team was Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, a former businessman widely seen as a political lightweight but whose abilities to manage strong personalities kept negotiations on track. Roosevelt planned to open the conference himself, but he died shortly before it began on April 25, 1945.

The 16th plenary session of the San Francisco Conference, 26 June 1945 (UN Photo/McCreary).

Negotiations in San Francisco proved as difficult for new President Harry Truman as his predecessor had predicted. Disagreements between the major powers (now the Big Five with the addition of France) continued, and small states sought equal status not just in the general assembly, but within the more exclusive security council.

In this latter area, both Britain and the United States had flirted with weakening or even eliminating the veto. Such a measure would have sacrificed some level of national sovereignty by committing the states to aid threatened nations in response to a majority vote by the security council.

The Soviet Union balked, however, responding with demands for an absolute veto. The USSR believed an effective incorporation of the “Four Policeman” idea into the security council was necessary to protect its interests in Eastern Europe. The debate nearly scuttled the conference, but eventually the Big Five united behind a powerful veto that demanded superpower unanimity on all security votes but could not block discussions of topics within the security council.

A poster showing the permanent organs of the United Nations circa 1945.

In these discussions, Vandenberg and Dulles proved invaluable additions to negotiations. The two were particularly active in addressing issues pertinent to Latin America.

Believing the Senate would demand the United States maintain traditional U.S. influence in the region, they responded to official Latin American concerns about communist infiltration.

They wrote in language that grandfathered existing statements of hemispheric interest such as the Monroe Doctrine and allowed for regional “self-defense” pacts that could operate before the UN intervened. This latter compromise became the legal basis for organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance.

A final concession by the United States and Great Britain to allow the General Assembly to discuss any pertinent issue closed the conference. Harry Truman attended the final signing ceremony on June 26th, challenging the assembled delegates: “Let us not fail to grasp this supreme chance to establish a world-wide rule of reason.” The Senate responded by approving the bill 89-2.

The UN would go on to define the contemporary idea of human rights, and its many associated institutions have been vital in promoting social and economic development. Yet the compromises made at San Francisco undermined its primary goal of ensuring peace. The permanent member veto hamstrung the security council as the Cold War pitted the Soviet Union against its wartime allies, and disagreements continue to hinder decisive UN action on key conflicts, such as the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea.

Nonetheless, the passage of the charter represented a new era of world affairs. Beyond the creation of the world’s major deliberative body, it signaled the beginning of a more expansive American foreign policy. A bipartisan unity allowed the country to support grand international projects and at least consider sacrificing small parts of U.S. sovereignty to do so.

That international compromises and the Cold War complicated this achievement should not distract from the promise of this moment, and the possibility that such unity of purpose might once more motivate U.S. foreign policy.