The Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau (Place of Refuge) National Historical Park is located on the Kona coast of the Big Island of Hawai‘i, next to the peaceful azure waters of Hōnaunau Bay. This 420-acre park holds great cultural significance as an ancient Hawaiian site and offers a fantastic opportunity to explore the history and culture of the island’s early inhabitants.

The Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau served as a place of safety and forgiveness in the past. Until the nineteenth century, Hawaiians followed a strict social order governed by laws known as kānāwai. These laws included kapu, or sacred rules that prohibited certain things, places, and actions. Breaking kapu, such as harvesting resources at the wrong time, carried a punishment of death.

Those who broke these laws could seek refuge and forgiveness from a priest, or kahuna, within a puʻuhonua designated by the aliʻi, or Hawaiian ruling class. Children, the elderly, and non-combatants could also find peace and shelter within a puʻuhonua during times of war.

Many such places existed throughout ancient Hawai‘i but the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau, established around 450 years ago, is one of the best-preserved examples of these sanctuaries and features remarkable instances of traditional Hawaiian architecture and sacred structures.

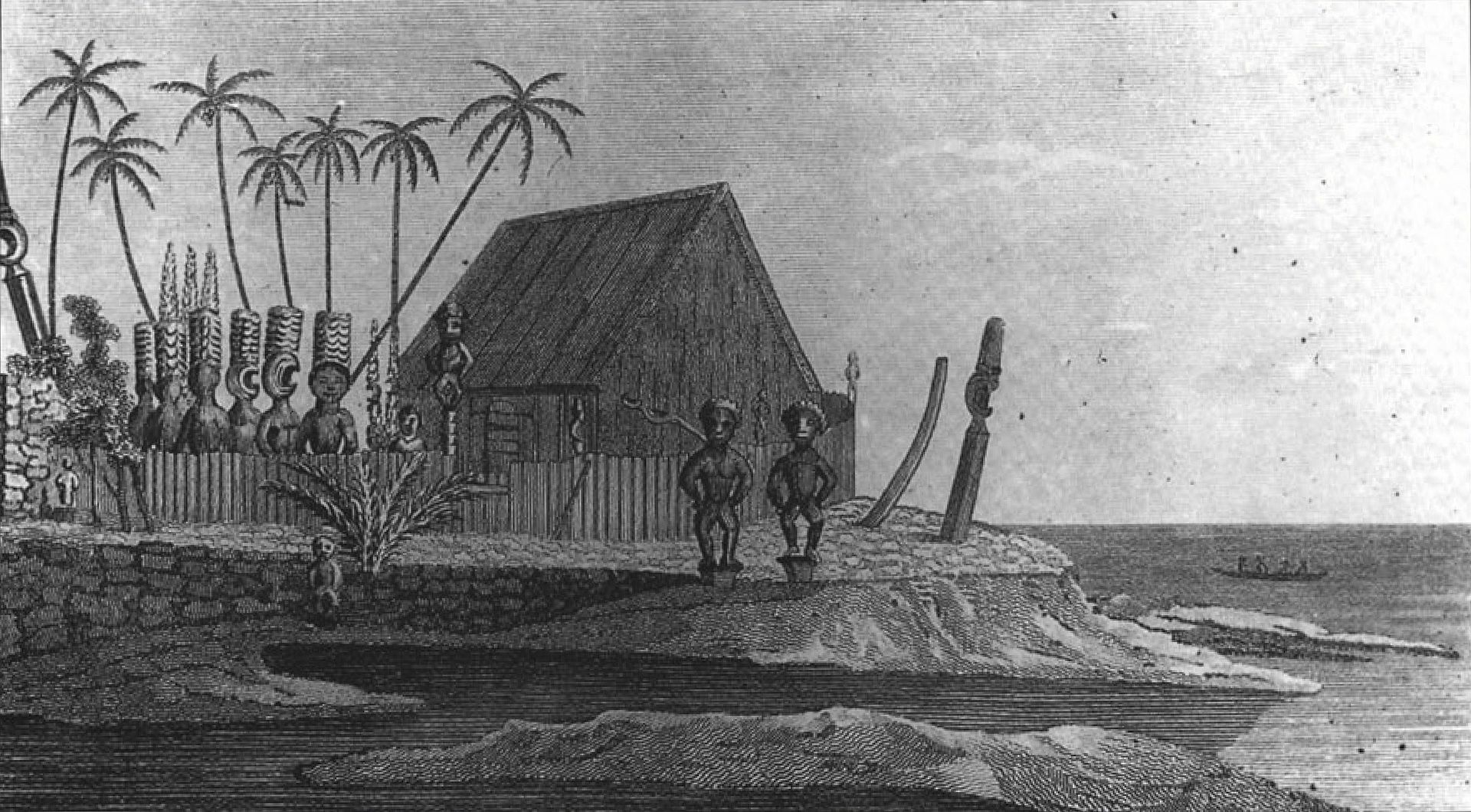

Visitors to the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau can view reconstructions of important ceremonial structures. One of these includes the Hale o Keawe, a sacred temple that housed the bones of 23 Hawaiian aliʻi. The spiritual power of these remains sanctified and legitimized this site as a puʻuhonua.

In 1829, Queen Kahumanu ordered the removal of the remains, which were interred in the Royal Mausoleum on O‘ahu in 1858. To many Hawaiians, this site still possesses immense spiritual power, or mana, and remains sacred to them.

In addition to the Hale o Keawe, the massive Pā Puʻuhonua (Great Wall), a 400-year-old structure built using dry-set masonry, is one of the park’s most impressive structures. The wall measures 12 feet high, 18 feet wide, and 965 feet long. The imposing structure marks the boundary between the Puʻuhonua and the site’s Royal Grounds.

Within the Royal Grounds, the ruling class would have rested and conversed with kahuna while workers prepared taro and caught fish from the royal fishponds. The park also features the remains of three hōlua slides, which were used for a deadly sport— reserved only for the aliʻi —that involved racing down steep slides constructed in the sharp lava rock on toboggan-like sleds (papahōlua).

A short hike takes visitors to the remains of Kiʻilae, a nearby fishing village inhabited by Native Hawaiians from ancient times until the 1920s. Here, visitors can see the remains of houses and other evidence of its past inhabitants.

The park also features beautiful scenery and engaging cultural exhibitions. Visitors can spot sea turtles and yellow tang in the clear waters of Keoneʻele Cove, learn to play kōnane (a traditional Hawaiian game that resembles checkers), watch cultural practitioners give demonstrations in making poi (pounded taro) and kapa cloth, and take a guided walk through the grounds with a park ranger.

The Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau began its journey into the National Park Service in 1868. Charles Bishop—an American businessman who married into the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi’s royal family—purchased the land that would become Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historic Park that year as a gift for his wife, Bernice Pauahi Bishop.

In 1891, the land was deeded to the Bishop Estate Trustees, who then leased the land to the County of Hawaiʻi from 1921 until 1961 for a public park. Given the historical and cultural significance of the site, Congress authorized the Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau’s establishment as a national historical park in 1955, and the park was formally created on July 1, 1961.

Since being acquired by the National Park Service, the Puʻuhonua has undergone important restoration and developmental projects. The Park Service worked with the local community to restore the Pā Puʻuhonua and reconstruct the Hale o Keawe using archeological and historical research in conjunction with traditional Hawaiian building methods and cultural practices.

Today, Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park is an incredible place to learn about and reflect on, the complex culture of the ancient Hawaiians and the world they inhabited. It is also an important place for Native Hawaiians who continue to foster deep relationships with this sacred site.

![]()

Sources and Additional Resources:

Linda Wedel Greene, A Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites on the west Coast of Hawai’i Island, September 1993.

National Park Service, Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park.

National Park Service, Foundation Document Pu‘uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, September 2017.

National Park Service, Great Divide Pictures, Hawaii Pacific Parks Association, “Those Are My Ancestors,” n.d.

V. Aubrey Neasham, Historic Site Survey Report: Place of Refuge, November 1949.