When the Soviet Union dissolved and became the Russian Federation at the end of 1991, the Cold War came to an end. Many wondered whether the North Atlantic Treaty Organization—NATO—had any purpose in a post-Cold War world. Yet, NATO not only continues today but is expanding. As historian Mark Rice reminds us, NATO’s mission has from the very beginning been as much political as military. 25 years later, with Russian leader Vladimir Putin taking an increasingly aggressive attitude toward the West, are both roles as urgent as ever?

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on Europe: The Ukrainian Crisis; Stories from Crimea; Putin and Russian Politics; Russian-Georgian War; 1989 and the End of Communism; Kosovo's Independence; European Disunion; Socialism in France; and the Czech and Slovak Republics.

Listen to great History Talk podcasts on 1989: The Year That Changed It All; The Fate of Crimea, The Future of Ukraine, Part I and Part II.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Twitter Cold War

Reading the headlines over the past weeks and months, it seems like déjà vu all over again.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) announces plans to expand its military presence in central and Eastern Europe. The United States military begins preparing for war against Russia again, unveiling plans to quadruple military spending in the region and deploy more heavy weapons, armored vehicles, and other equipment.

NATO-member Turkey shoots down a Su-24 Russian warplane. Russian warplanes fly through the English Channel. Russia transfers new missiles to Kaliningrad. NATO countries station new air forces in the Baltic states (PDF File).

And the fall of Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovich (below, left) in 2014 and the outbreak of fighting in eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian forces and Russian separatists sparks a rapid rise in tensions between Russia and NATO.

|  |

Many observers have noted a return to some of the conditions of the Cold War that defined international politics between 1945 and 1991. Some have even proclaimed the start of a new Cold War between East and West. A few believe the new tensions may lead beyond a new Cold War, to a new world war.

NATO’s secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg (above, right), described the proposed expansion of NATO forces in Europe as “multinational, to make clear that an attack against one ally is an attack against all allies, and that the alliance as a whole will respond.”

The blame for these tensions is difficult to assign. Some point to Russia for reacting to the fall of its ally Yanukovich in Ukraine by sparking a civil war in eastern Ukraine, designed to weaken the new Western-leaning government of Petro Poroshenko (below, left) and pull Ukraine back firmly into the Russian orbit.

Others blame the United States and NATO for sparking the popular uprising in Ukraine that brought down Yanukovich, thus undermining Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin (below, right)

There is certainly evidence to support both perspectives.Each side increasingly regards the other’s actions as provocative and dangerous, amplifying the sense of tension and competition across Europe and strengthening the sense of impending conflict between Russia and NATO.

As Russia has emerged from the chaos and economic troubles that characterized the initial years after the fall of the Soviet Union, it has become more assertive on its borders and less willing to cooperate with other European states. Under Putin, the Russian state has become more centralized and autocratic. Dissent, including opposition to the country’s foreign policy, has been stifled.

Yet at the same time, the United States and Europe have pushed further east toward Russia’s borders, mainly through the institutions of NATO and the European Union. They have moved their sphere of influence east in spite of Russian objections, raising long-standing Russian fears of encroachment on its traditional sphere of influence.

NATO itself has become more willing to take an active role in areas outside its normal scope, moving from a deterrent protecting Western Europe to operations in the Balkans and Afghanistan.

Yet looking at the history of NATO shows that since its origins in 1949 the alliance has often changed its mission, its strategy, and even its geographic scope of membership and activity. These changes have mostly been adaptations to internal or external shifts in NATO’s operating environment. The most dramatic shift came at the end of the Cold War, when the alliance found it needed to justify its existence after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Starting with the formation of NATO itself, changes were often driven by political rather than military or strategic factors. The alliance has always needed to keep an eye on its internal political cohesion, to ensure that it speaks with one voice to the extent possible.

While it may look like NATO’s expansion and new missions after the Cold War were designed to provide a military or strategic advantage over its former Russian adversary, they were often driven more by a desire within the alliance to solidify itself politically, while at the same time trying to avoid upsetting the global political balance.

The Roots of NATO

NATO was founded in the early years of the Cold War, as relations between the former allies of World War II (the Soviet Union, Britain, France, and the United States) broke down. Disagreements over the future of Germany, the growing division of Europe, and increasing ideological competition created an adversarial relationship between the Soviets and the Western allies

As the Soviets gained control over the countries of Eastern Europe that they occupied during the war, the Western allies reacted by tying Western Europe more closely together, including the western portion of Germany. But the political and economic situations in Western Europe were still unstable and some feared communist-led governments could take power in countries like Italy and France.

These fears prompted leaders in Western countries, including the United States, to seek new ways to strengthen anti-communist governments. Much of this support was economic, through the Marshall Plan for European reconstruction.

|

Some of the support was military, as promised by the so-called Truman Doctrine. President Harry Truman articulated this position to the nation as he announced American military assistance to the Greek and Turkish governments fighting communist-supported guerillas.

But the threat remained. In February 1948, when communists in Czechoslovakia staged a coup and evicted non-communists from the government, it appeared that the continuing instability in Europe might facilitate the further spread of Soviet communism.

In the wake of the Czechoslovakian (PDF File) coup, leaders in Western Europe began to look for ways to solidify the region against this communist threat. In March 1948 Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg signed a treaty for mutual defense, later known as the Western European Union.

These countries all recognized that they were too weak properly to defend one another against outside threats, particularly the Soviet Union, and realized that the only country capable of providing such defense was the United States. However, despite the extension of American involvement through the Marshall Plan and the military assistance promised by the Truman Doctrine, it was still unclear what role Americans wanted to play in postwar Europe.

American leaders recognized that, while the economic and military assistance was vital to the reconstruction and stabilization of postwar Europe, the overall political situation was still uncertain, and Europeans needed more than military aid to ensure security.

As the sense of crisis heightened after the Czechoslovakian coup and the subsequent Berlin Blockade in 1948-1949, the U.S. government began talks with the Western European Union members, along with Canada, to shape a larger treaty structure that would involve the United States in the defense of Western Europe.

|

The implications of such a treaty were significant. It would be the first peacetime American alliance with European states since the immediate years after the American Revolution, and would commit American military, economic, and political power to Europe. This assurance would send a strong signal to the European public that the United States was committed to ensuring the stability of Western Europe, thus preventing other governments from potentially appeasing the Soviets and falling under their influence.

The Washington Treaty of April 1949 bound the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, Norway, Denmark and Iceland into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

The Treaty recognized the political role of this new alliance. Its key military provisions came in Article III and Article V. The former called for close military coordination between the treaty signatories, and the latter stated that an attack against one ally was an attack against all of them.

Just as importantly, the treaty included Article II, which called for the “further development of peaceful and friendly international relations by strengthening their free institutions, by bringing about a better understanding of the principles upon which these institutions are founded, and by promoting conditions of stability and well-being.”

Pushed by the Canadian delegation, Article II was designed to demonstrate that NATO was to be more than a strictly military alliance, and sought broader political goals for its members.

NATO as a Cold War Institution

In its initial months, this political role seemed to be more important than the military side of the new alliance. Limited defense budgets on both sides of the Atlantic, a reduced sense of urgency after the end of the Berlin Blockade, and uncertainty regarding the larger role of the alliance created a sense of stasis.

|

It was only after the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, and the resulting fear that Soviet communism was becoming more aggressive, that the allies began organizing their militaries under a new defense organization, with a command structure and permanently assigned units. These included American forces stationed in West Germany.

Significantly, NATO matched these military developments with political ones. The new treaty organization also included the new North Atlantic Council, with permanent representatives at the ambassador level and chaired by a permanent Secretary-General with a dedicated staff, to coordinate the alliance’s political positions.

|

For the remainder of the Cold War, NATO’s structure and role remained largely the same, even as the environment around it changed.

Most notably, the Soviet Union gathered its Eastern European allies into a rival organization, the Warsaw Pact, in 1955. Throughout the remainder of the Cold War, until the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991, the two blocs faced off against each other in a nuclear standoff.

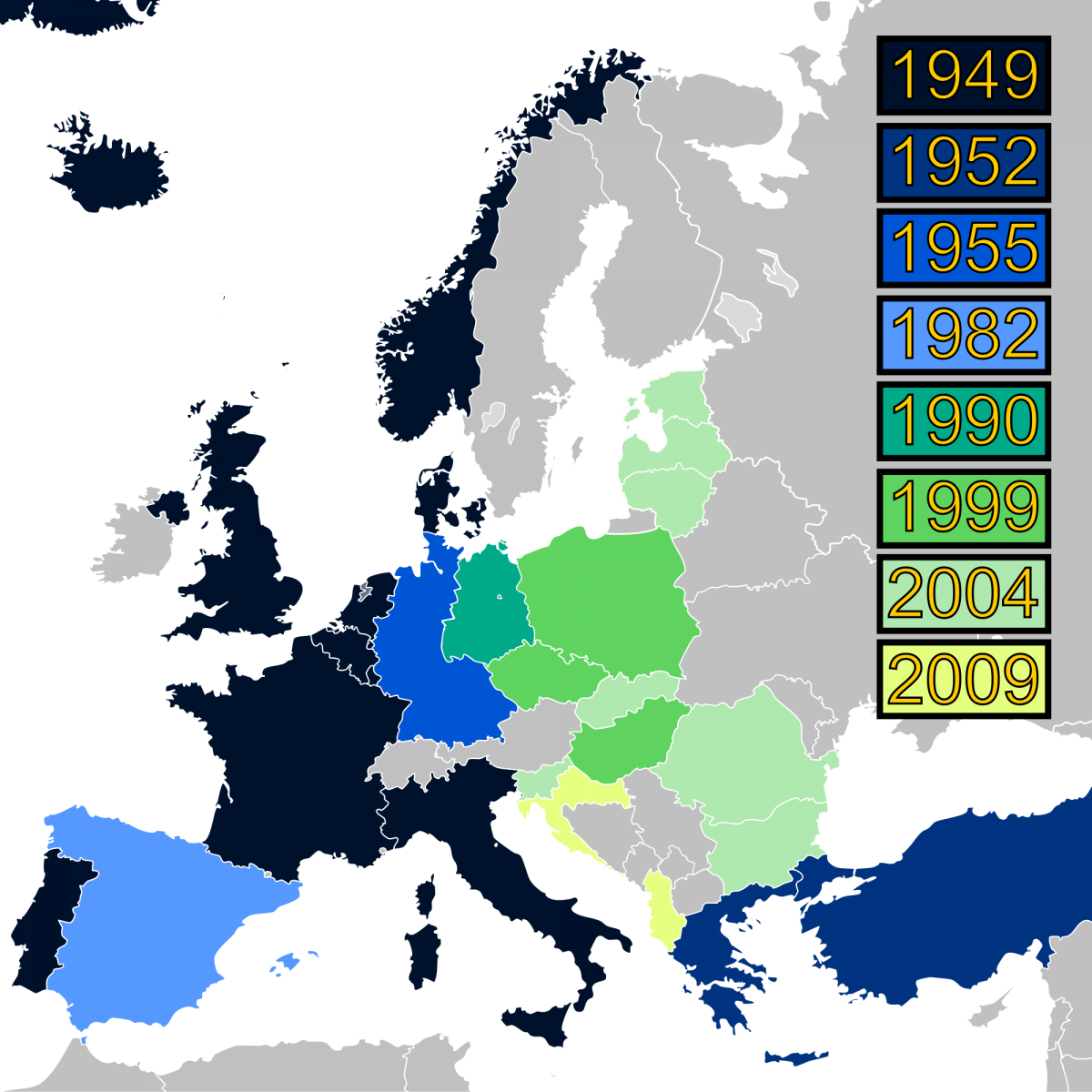

The main changes that NATO underwent during these decades were the times it expanded its membership, adding Greece and Turkey to its southeastern flank in 1952, West Germany in 1955, and Spain in 1982. While both the West German and Spanish expansions were militarily useful, they also served important political purposes.

Throughout the 1950s, plans put forward about removing Germany as a threat to peace by making it a neutral, largely disarmed country raised the worries of instability in central Europe that might once again drag the continent into war. Given Germany’s size and economic potential in the heart of Europe, these neutralization plans created the possibility of a power vacuum that one side or the other might seek to fill.

Bringing West Germany into NATO forestalled that possibility, legitimized the new Federal Republic, and gave West Germans assurance that their new allies would not desert them in case of Soviet aggression. Similarly, the accession of Spain following the end of the Franco dictatorship in the late 1970s legitimized the nascent Spanish democracy.

By the time the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union collapsed two years later, NATO, created as part of the Cold War, had become central to European security. Yet the end of the Cold War raised questions about the alliance’s future, since its prime function, defending Western Europe against the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies, no longer seemed necessary.

|

There were calls for NATO to disband and turn over its security position to the United Nations or new organizations like the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE). Despite changed geopolitical circumstances, most nations in Europe, both those inside and outside of NATO and including many former Warsaw Pact countries, continued to see the alliance as the preeminent source of stability and security on the continent.

|

While post-Soviet Russia appeared weak, none of its former allies wished to return to the position of client to their eastern neighbor, should Russian power and aggression revive. As a result, NATO not only remained in place, but also grew to include new members.

NATO in a New World

NATO faced its first post-Cold War challenge immediately after the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989. As East Germany collapsed into disorganization, it became increasingly clear that the only way to stabilize the state was for West Germany to absorb the former communist territory.

One of the main sticking points of re-unification, however, was that if East Germany joined the Federal Republic it would become a part of NATO. The Soviet Union objected. In the initial meetings after the fall of the Berlin Wall, American leaders sought to appease Soviet concerns, offering to assure them that NATO forces would not expand eastward in Germany. These early offerings helped smooth the negotiations towards the reunification of Germany a year later.

However, American and West German officials soon realized it would not be possible for Germany to reunify without East German territory becoming a part of NATO. Without NATO being able to operate in the east, that territory would be difficult to defend, and East German citizens would not accept less protection than their new German compatriots in the west received. Thus, the American position in the negotiation changed at a very early point, from assurances that NATO forces would not expand eastward in Germany, to requiring that East Germany be allowed to join NATO with few, if any, limitations.

Even though they were at first opposed to these terms, Soviet and East German officials did accept them. They realized that, as the situation in East Germany deteriorated and East German citizens expressed the desire to join West Germany, and by extension to join NATO, it would be better to negotiate concessions for the USSR than to lose East Germany totally.

Thus, the final agreements, both bilateral between East and West Germany and multilateral between the other actors, recognized that the territory of East Germany would become a part of NATO. In return, the West agreed to a lenient timeline for the removal of Soviet forces and provided billions of dollars in aid to help redeploy and resettle these troops in Russia.

Perhaps more importantly, the final agreements also recognized that all of the states of Europe were free to choose which alliance, if any, to join. This principle was first expressed in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, which stated that the signatory states “have the right to belong or not to belong to international organizations, to be or not to be a party to bilateral or multilateral treaties including the right to be or not to be a party to treaties of alliance; they also have the right to neutrality.”

The popularity of NATO membership became clear a few years later, when the former Warsaw Pact countries of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary began pressing the United States and NATO for inclusion. These states were struggling with the transition from communism to democracy, and saw NATO as a means to strengthen themselves politically and militarily, allowing room for economic development that would provide new prosperity and the possibility to join the burgeoning European Union. They also saw NATO as a means to provide themselves with additional security from possible Russian aggression.

It bears repeating that as NATO was trying to redefine itself in the post-Cold War environment, it was not looking to expand. Many of the original allies, including Britain and France, did not think expansion provided any advantage, views echoed by the American military.

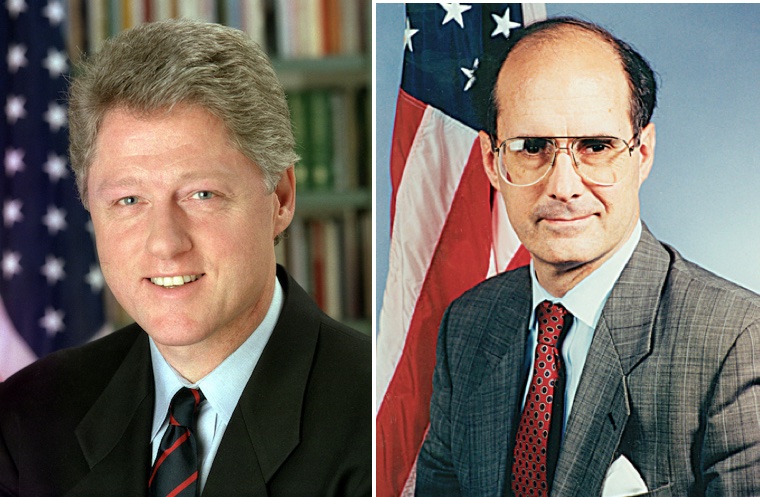

But many American and Western officials, including President Bill Clinton (below, left), came to see NATO enlargement as a useful means for ensuring political stability in an increasingly unstable Europe.

In the words of senior State Department official Strobe Talbott (above, right) in 2000: “we said that [freezing NATO in its Cold War membership] would mean perpetuating the Iron Curtain as a permanent fixture on the geopolitical landscape and locking newly liberated and democratic states out of the security that the Alliance affords. So instead, we chose to bring in new members while trying to make a real post-Cold War mission for NATO in partnership with Russia.”

For supporters of expansion, a larger NATO would provide security to democratizing countries, solidifying their transitions from communism and opening new economic prosperity through greater connections with the European Union, including potentially membership there. Critics of enlargement argued that the new members would not offer NATO much military or strategic benefit, and that those countries would be better served through other organizations, including the OSCE and EU.

NATO began evaluating candidates for military and political readiness. In addition to having significant military forces to contribute to NATO’s collective defense mission, NATO leaders looked for civilian control of the military, stable domestic political processes, and peaceful resolution of ethnic and national disputes.

In 1999, NATO judged that Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic met these criteria, but found that other countries like Slovakia needed more time to adjust their domestic politics to more liberal democratic norms.

Peaceful Co-existence or Existential Threat: The Russian View of NATO

Post-Soviet Russia raised some objections to NATO enlargement into Eastern Europe. Many Russian officials believed that expansion contradicted American promises during the negotiations over German reunification, despite the language of the final agreements regarding states’ rights to choose their own alliances. There were also claims that NATO expansion was directed against Russia, intended to surround the country with adversaries and reduce its ability to act independently in its former sphere of influence.

|

Although Russia’s position was weak following the break-up of the Soviet Union and the decline of the economy in the 1990s, many Russian officials still saw the country as having a natural sphere of influence, extending in some cases to Eastern Europe. Thus, at least some Russians saw former Warsaw Pact countries opting to join NATO as a threat to this sphere of influence.

American and Western leaders were not blind to Russian concerns. Even though prospective members initiated the call for membership, despite whatever reluctance within NATO, there was a recognition that such enlargement could not happen without taking into account Russian concerns.

Early in the process, President Clinton told Russian President Yeltsin that he “want[ed] to work closely with you to get through it together.” NATO looked to open itself up to new cooperation with its former adversary, so that enlargement “would be part of a broad European security architecture based on true cooperation throughout the whole of Europe. It would threaten no one and would enhance stability and security for all of Europe.”

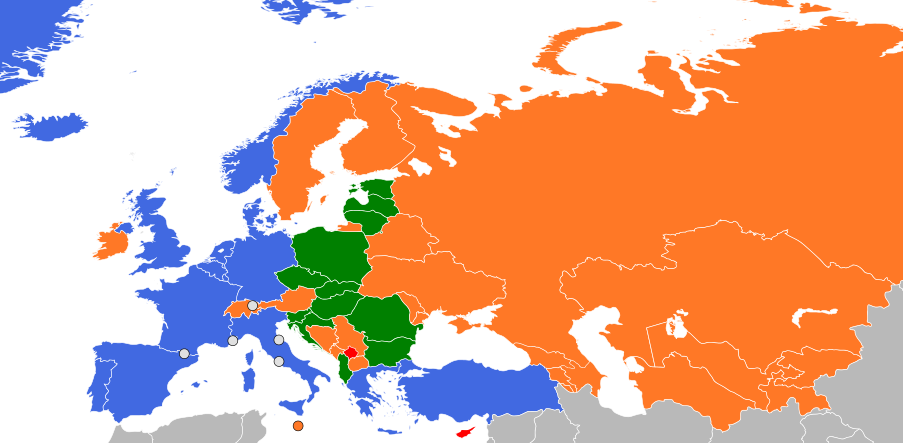

The first step was NATO’s creation of the Partnership for Peace program (PfP) in 1994. This program was open to all of the former Warsaw Pact countries and the rest of Europe, and was designed to open larger collaborations toward overall peace and stability in Europe.

|

Russia gained special consideration within PfP, given its unique geopolitical circumstances. PfP was not a formal arrangement, and did not provide non-members much access to the alliance or its decisions. It was, however, a recognition that NATO could not act unilaterally in Europe, especially outside its area.

NATO took even larger steps to bring Russia closer to the Western alliance. Clinton pushed a new partnership embodied in the NATO-Russia Founding Act signed in May 1997, which created the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council (PJC) to provide Russia a voice within the alliance itself.

|

The PJC was not a decision-making body because Russia was still outside of the alliance. But it did provide a consultative arena for Russia to influence NATO policy, especially as the alliance expanded. Yeltsin recognized “the readiness exhibited by the NATO countries, despite … difficulties, to reach an agreement with Russia and take into account our interests.”

However, the council never lived up to its goals. It acted in a 16 (later 19)+1 format, where the allies brought issues to Russia as a body, and Russia could only raise objections after the fact. As a result, Russia largely ignored the council, which fell into irrelevance.

One of the main issues that NATO and Russia faced in the 1990s was the disintegration of Yugoslavia (PDF File) and ensuing violence. As the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina deepened, NATO authorized airstrikes against Bosnian Serb forces in 1995. Russia opposed these attacks against their traditional Serbian allies, but was unable to do much more than object, although they were included in the negotiations that led to the Dayton Peace Accords ending the war in 1995.

These disagreements continued as the conflict in the former Yugoslavia continued, now centered on the Serbian province of Kosovo. As the ethnic violence between Serbs and Kosovars intensified, NATO again became directly involved, launching airstrikes against Serb forces in 1999.

|

Again, Russia objected on behalf of their Serb allies, but could do little more than they had been able to in Bosnia. As before, Russia was only able to involve itself in the cease-fire negotiations, although Russian forces also contributed to the Kosovo Stabilization Force (KFOR) that NATO deployed to Kosovo following the cease-fire.

|

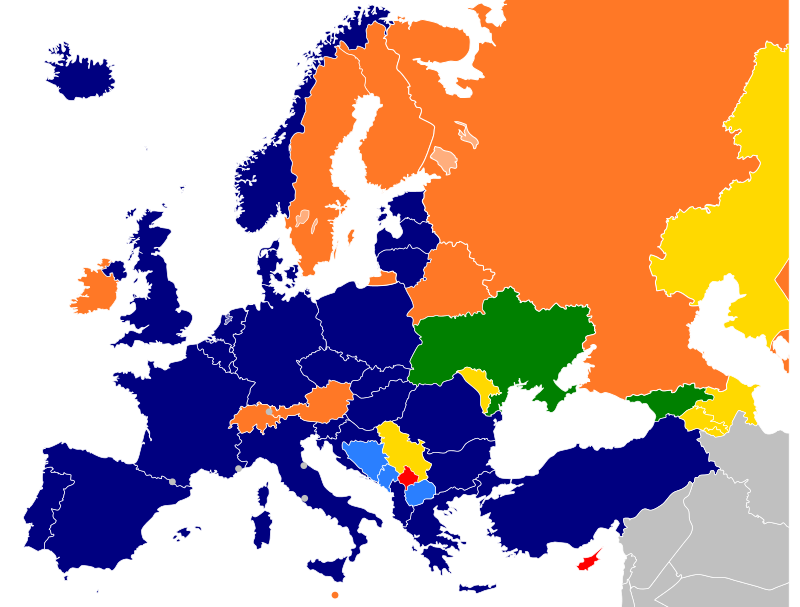

Throughout the 1990s, NATO found itself in a changing environment, trying to redefine itself both geographically and existentially. The desire among many Central and Eastern European countries to join the alliance, led by Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary, made NATO enlargement a central, contentious issue for NATO-Russian relations.

The conflicts arising out of the disintegration of Yugoslavia exacerbated tensions between NATO and Russia, although in general relations between the two sides remained calm, helped by the close personal relationship between Clinton and Yeltsin.

NATO and a Resurgent Russia

That is how things stood at the start of the first decade of the 21st century, even as Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia. Although many Russians were still upset over NATO enlargement, it was accepted reality by this point and many Russian officials recognized that its work was more political than military.

The reduction of violence in the former Yugoslavia alleviated tension between Russia and NATO. In fact, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, NATO and Russia found themselves closely aligned on a major issue, as both saw Islamic extremist terrorism as a threat.

In response, NATO adapted the Permanent Joint Council to the new NATO-Russia Council (NRC), giving Russia more collaboration in NATO policy. Unfortunately, the NRC proved little more capable at improving NATO’s relations with Russia than the PJC had, and, in the words of U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (below, right), “made little progress, because the Kremlin never fully embraced it.”

As Russia’s economy improved, many of the contentious issues returned and were joined by new ones like missile defense in Eastern Europe. In response to growing nuclear proliferation fears in the Middle East, especially Iran, the United States looked to Eastern Europe as a base for deploying anti-ballistic missile forces that could protect Europe and the United States from smaller attacks. Russia, however, saw these deployments as actions directed against it, believing that the United States sought to gain strategic advantage over Russia by eliminating Russia’s nuclear deterrent threat.

Starting in 2002, a new set of central and eastern European states sought admission in NATO. In addition to states like Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania that NATO had not accepted in the first round, the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia(PDF File) sought membership. These states posed a new matter beyond additional NATO enlargement, as they would be the first former Soviet Union states to be admitted to NATO, and would directly border Russia.

Russia again objected to this expansion, citing concerns about bringing an alliance from which it was excluded right up to its borders. In the end, President Putin was not willing to place the issue of Baltic membership in NATO in the way of improving Russia’s relationship with the alliance.

The expansion arguments won within NATO and, in 2004, the alliance added Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the three Baltic states. In 2009, Albania and Croatia joined.

Furthermore, NATO created the Membership Action Plan (MAP) in 1999, a program designed to aid prospective states looking to join in the future. Along with several Balkan states, the former Soviet republics of Ukraine and Georgia began working through the MAP process in hopes of gaining NATO membership.

|

As the first decade of the 2000s progressed, a stronger central government under Vladimir Putin sought to raise Russian influence in the states along its long western and southern borders. Much of this new influence was directed toward Central Asia, where Russia sought to build a new Eurasian Union to balance the European Union to the west.

Russia also turned renewed attention to Ukraine, where, after a pro-Western interregnum beginning with the 2004 Orange Revolution, a pro-Russian government held power after 2010. In 2008, Russia used a simmering sectarian conflict in Georgia to invade its smaller neighbor and reassert its influence.

The Russian moves along its borders culminating in the 2008 war in Georgia did deter further NATO enlargement for the moment. The alliance dropped plans for expanding to Ukraine and Georgia, while keeping the door open for including them at some point in the future.

The 2014 overthrow of the pro-Russian government of Viktor Yanukovich in favor of the pro-Western government of Petro Poroshenko, and the subsequent Russian annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the outbreak of violence between Russian-supported separatists and Ukrainian forces in eastern Ukraine, again set back plans for further NATO enlargement.

Both the conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine also set back NATO-Russian relations, with the West reacting to Russian moves on its neighbors with sanctions and other diplomatic maneuvers.

|

Created out of Cold War circumstances, NATO has now operated for 25 years in a post-Cold War world. Has this new NATO attained its goals?

If NATO expansion in the 1990s and 2000s was designed to increase its military power, especially vis-à-vis Russia, then the results are debatable. While NATO has added new manpower to its forces, it also has more territory to defend, much of it away from its economic and military center in the United States and Western Europe. The Alliance has worked, especially since the Ukraine crisis, to expand its military power in Eastern Europe, but defending that territory is still based largely on the principle of deterrence.

However, looking at NATO expansion from a political standpoint, the results have been more successful. Along with EU expansion, NATO has brought stability and democratic norms to post-communist Europe. The goal of attaining NATO membership has forced these states to meet the standards set by the Alliance, including open elections, civilian control of the military, and elimination of ethnic and national conflicts. The security NATO has offered these states has given them the room to prioritize internal reforms over confronting external conflicts.

The West went into the post-Cold War period emphasizing, as President George H.W. Bush did, that “no one had lost the Cold War, but everyone had won.” NATO took steps to turn Russia into a partner rather than an adversary, but that effort presently seems to have been unsuccessful, and Russia still sees NATO as its primary antagonist.

NATO will now have to reevaluate its approach to Russia, likely placing more emphasis on military force. While this condition will likely not rival the Cold War in its intensity or danger, it will still represent a major source of international instability into the future.

Ronald D. Asmus, Opening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2002.

--------------, A Little War that Shook the World: Georgia, Russia, and the Future of the West. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

James M. Goldgeier, The Future of NATO. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, 2010.

Lawrence S. Kaplan, NATO and the United States: The Enduring Alliance. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, 1994.

F. Stephen Larrabee, NATO's Eastern Agenda in a New Strategic Era. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2003.

Mary Elise Sarotte, 1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Lilia Shevtsova, Lonely Power: Why Russia Has Failed to Become the West and the West Is Weary of Russia. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2010.

Angela E. Stent, Russia and Germany Reborn: Unification, the Soviet Collapse, and the New Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

--------------, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Edited Volumes

Gülnur Aybet and Rebecca R. Moore, eds., NATO in Search of a Vision. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2010.

Derek Chollet and James Goldgeier, eds., America Between the Wars: from 11/9 to 9/11. New York, NY: Perseus Books, 2008.

Primary Sources

Conference On Security And Co-Operation In Europe Final Act, Helsinki 1975, Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, http://www.osce.org/mc/39501?download=true

NATO E-Library, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/publications.htm.

The Partnership for Peace Programme, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_50349.htm, updated 31 March 2014

Articles and Websites

Max Fischer, “How World War III Became Possible,” Vox, June 29, 2015. Available at http://www.vox.com/2015/6/29/8845913/russia-war

John Kornblum and Michael Mandelbaum, “NATO Expansion, A Decade On,” American Interest, Volume 3, No. 5, May 1, 2008. Available at http://www.the-american-interest.com/2008/05/01/nato-expansion-a-decade-on/