On a snowy afternoon in March 1907, Mary Mallon crouched breathlessly in a storage closet near the Park Avenue mansion where she worked as a cook.

Hours earlier, five police officers and a towering female health official had shown up, unannounced, demanding that Mallon, a healthy, 37-year-old Irish immigrant, get into an ambulance and go to a nearby hospital to provide a sample of her feces.

Mallon had reacted by waving a large kitchen fork at them and fleeing out the back door to her current hiding place, just under the stairs of the house next door.

This marked the third time that health officials had tried to corral Mallon.

In late 1906, after renters of a Long Island summer home developed typhoid fever, the home’s owner had hired Dr. George Soper, a noted sanitary engineer, to investigate. Initially, Soper was stumped: there was no indication that the home’s water sources or the milk the residents drank were contaminated.

But Soper learned that, just before the outbreak, the family had hired Mallon as their cook. Soper tracked down eight families for whom Mallon had worked as a cook over the prior decade. In seven, typhoid fever had spread shortly after Mallon had arrived, leading to a total of 22 cases and two deaths.

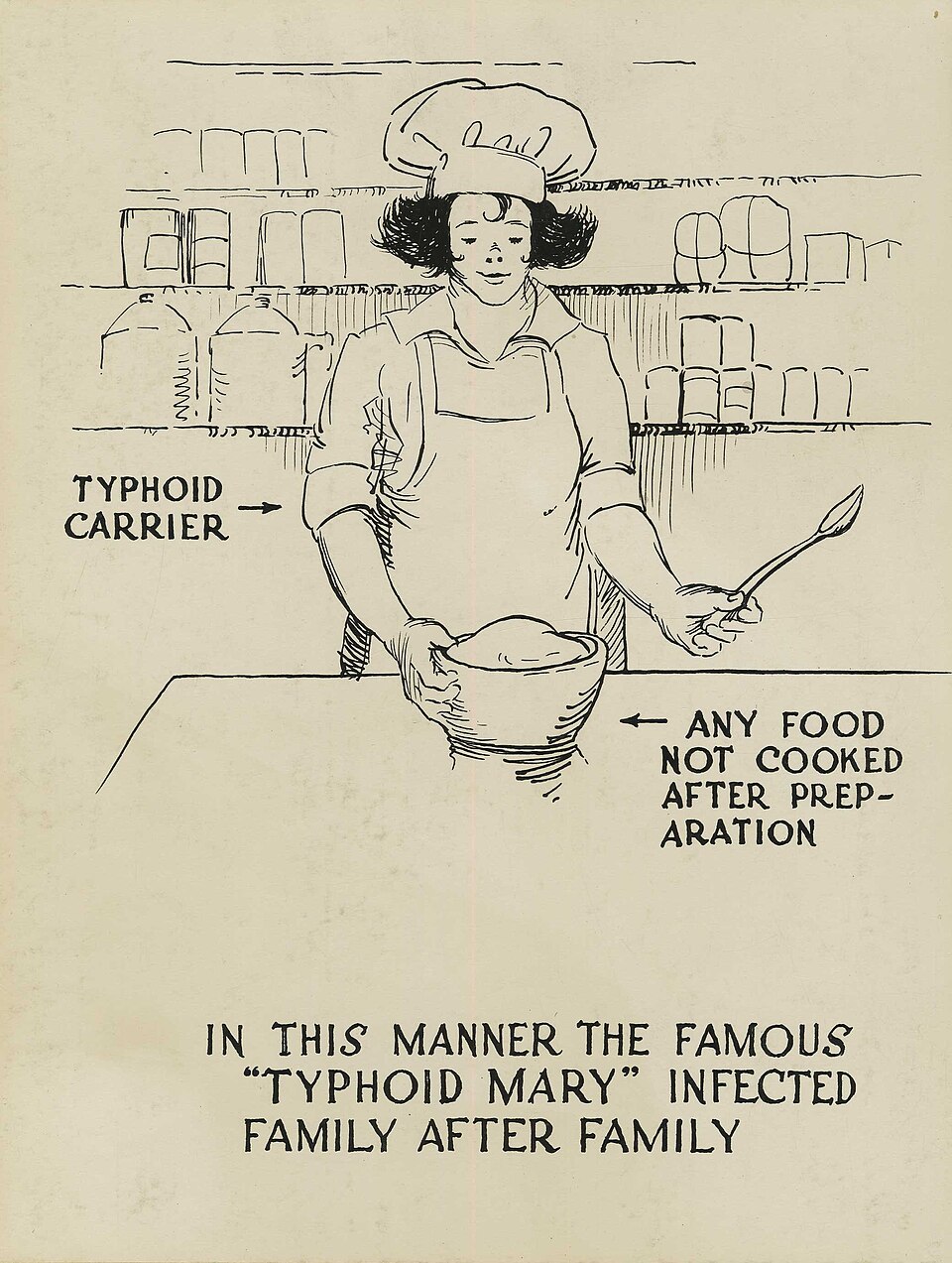

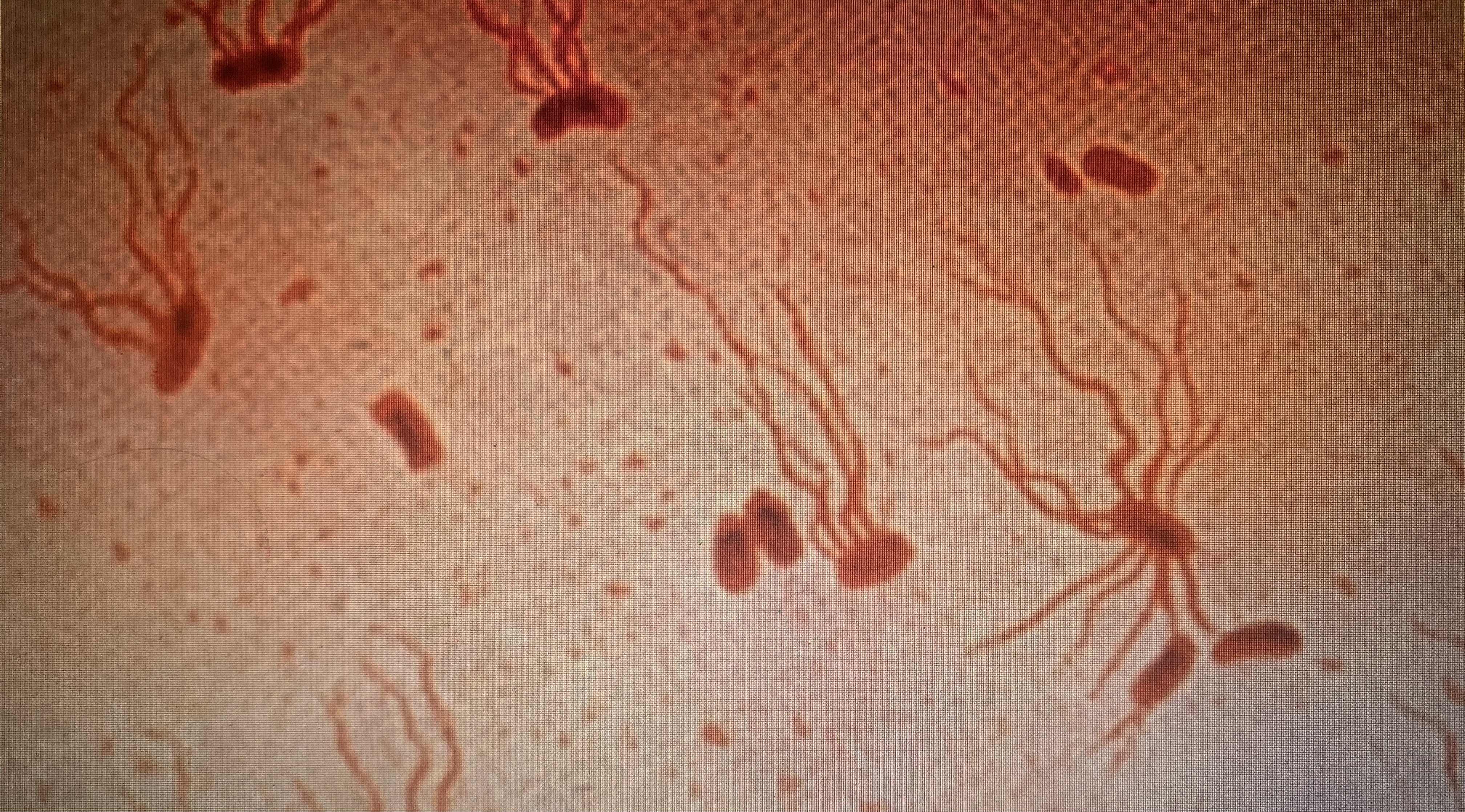

In 1884, the bacterium Salmonella typhi had been identified as the causal agent for typhoid, a serious gastrointestinal illness. Among those infected, the bacteria were carried in the feces.

They survived in sewage water or on infected peoples’ hands if people did not wash thoroughly after using the bathroom. When sewage seeped into drinking or bathing water, or when a person with typhoid germs on their hands handled food or milk and served it to others, the disease spread.

When Soper first approached Mallon to explain the situation and obtain a fecal sample for confirmation, she had angrily refused, insisting that she had never been sick. Soper knew that people could serve as “healthy carriers” for microbe-borne diseases.

No healthy carrier for typhoid had ever been identified prior to his investigation, but Soper was determined to prove that Mallon was the culprit. After Mallon had rebuffed him, he had approached the New York City health department for help.

Now, after five hours stomping around the mansion’s grounds in the snow, the officers spotted a swatch of calico dress fabric on the door of the under-stairs closet next door. They opened the door, dragged out Mallon, and pushed her into a waiting ambulance.

Dr. S. Josephine Baker, the female health official, sat on Mallon all the way to the hospital to keep her from resisting. Baker later described the trip as “being in a cage with an angry lion.” At the hospital, Mallon’s feces were tested and found to be full of typhoid bacilli.

Mallon had committed no crime. She had been unaware of her carrier status, and still did not believe that she was contagious. But the health officials decided that the public needed to be protected from her.

They sent Mallon to live on North Brother Island—a small island in the East River where the city ran a tuberculosis sanatorium. The Department acted under a provision of the New York City charter that gave the city Board of Health the power to “remove” anyone who was “sick with any contagious, pestilential or infectious disease” to a designated location.

In 1909, after articles about Mallon appeared in several newspapers, her situation caught the attention of an attorney, who sought her release. These efforts were unsuccessful but attracted public support for Mallon’s plight.

When a new health commissioner took office in 1910, he decided to release her if she promised never to work as a cook again and to take hygienic precautions to avoid infecting others.

After her release, Mallon struggled to find work. Health officials eventually lost track of her. Then in 1915, a deadly typhoid outbreak erupted at Sloane Maternity Hospital, infecting 25 and killing two.

Health officials located a “Mrs. Brown,” whom the hospital had hired as a cook. Brown, of course, turned out to be Mallon. Officials remanded her to North Brother Island, where she lived in a cottage with only a dog for a companion until her death in 1938.

In the interim, scientists discovered that many people were healthy typhoid carriers. Health departments realized that it would not be feasible or acceptable to round up all healthy carriers and send them to remote islands to live out their lives.

Instead, they decided to focus on people who worked in food handling occupations—those at highest risk of transmitting to others. Nevertheless, even when health officials identified healthy typhoid carriers who worked in restaurants or dairies, they were reluctant to do more than try to persuade these people to stop doing this work, and follow up with them periodically.

It has been over a century since Mallon’s second quarantine, but her story remains relevant.

COVID-19, along with measles, tuberculosis and other returning or new infectious diseases present continuing dilemmas for health officials over how to balance respect for personal liberty with the need to protect the public against deadly contagions.

In 2020, when a COVID-positive homeless person in Spokane, Washington, refused to self-isolate, a local health official sent him to jail. Other health officials have taken similar measures when people with contagious tuberculosis refused to quarantine and take medicine to cure it.

These measures have proven controversial. While other topics now occupy the headlines, future outbreaks of infectious disease are likely to once again raise the question over how much health officials seeking to protect the public from infectious disease should be able to limit the personal freedoms of people who are contagious.

![]()

Learn More:

Ashurst, John V., Justina Truong, and Blair Woodbury. “Typhoid Fever (Salmonella Typhi),” StatPearls [online book] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 30085544. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519002/.

Bourdain, Anthony. Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010.

Hasian, M.A. Power, Medical Knowledge, and the Rhetorical Invention of “Typhoid Mary”. Journal of Medical Humanities 21, 123–139 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009074619421

“Individual who tested positive for COVID-19 being held in Spokane County Jail after refusing to self-isolate,” NBC Right Now (Tri-Cities, Yakima, WA), July 2, 2020, https://www.nbcrightnow.com/regional/individual-who-tested-positive-for-covid-19-being-held-in-spokane-county-jail-after-refusing/article_ee6606ca-a4b2-5dec-824c-c0d4f184d1e9.html

Leavitt, Judith Waltzer. Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), pp. 16-18, 27-29, 45-46, 71.

“Spokane health officer issues order to jail COVID-19 positive man who refused to self-isolate,” Spokesman-Review (Spokane, WA), July 2, 2020. https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2020/jul/02/spokane-health-officer-issues-order-to-jail-covid

Teicher A. Typhoid Mary Was Not a Super-Spreader (and Super-Spreaders Are Not "Typhoid Marys"). Am J Public Health. 2023 Dec;113(12):1249-1253. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307434. Epub 2023 Oct 12. PMID: 37824810; PMCID: PMC10632844, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37824810/

“Tuberculosis patient in Washington who was arrested for refusing treatment is finally cured,” NBC News, July 23, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/washington-tuberculosis-patient-cured-arrested-refusing-treatment-rcna163302.