And the spirits that burn in the Baghdad sky

Insist there’s a price we must pay

A soldier returns from the war in the Gulf

A soldier named Tim McVeigh . . .

―Charlie King, The War is Coming Home, 1996

On April 19, 1995, a date fraught with meaning for American white supremacists, former soldier Timothy McVeigh—along with several accomplices—detonated a three-and-a-half ton fertilizer bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The explosion, which killed 168 people and wounded 500 more, remains to this day the deadliest act of terrorism carried out by a U.S. citizen on American soil.

Charlie King’s antiwar anthem highlighted the connections between American military actions abroad, militarized policing at home, and domestic terrorism. Historian Kathleen Belew’s riveting new book, Bring the War Home, builds upon the folk singer’s insight. Belew positions the Oklahoma City bombing squarely within the longer history of a White Power movement that had its genesis in the Vietnam War, and that continues to reverberate today.

Belew advances two main theses throughout the book. The first is the centrality of the Vietnam War experience to a new wave of white supremacist activism. Movement pioneers like Vietnam veteran Louis Beam told their followers “a story of soldiers’ betrayal by military and political leaders and of the trivialization of their sacrifice.” Steeped in a culture of warfare and fueled by outrage at a lack of appreciation for their service, White Power activists increasingly waged war not only on people of color, but on the state itself.

The book’s second contention is that the white supremacist movement after Vietnam was far more interconnected than either the media or the U.S. government has generally depicted it. Belew connects Klan chapters, Christian Identity churches, Aryan Nation compounds, and Central American mercenaries, among others and concludes that these seemingly disparate groups comprised a cohesive movement she places under the umbrella of “White Power.” Leaders like Louis Beam and William Pierce were important in these circles. Most significantly, written materials, especially the apocalyptic novel The Turner Diaries (written by Pierce under a pseudonym), circulated within and between all of the White Power subgroups.

The Turner Diaries, published in 1978 and set about twenty years in the future, tells the story of a successful white racist revolution. Belew contends that the novel “worked as a foundational how-to manual for the movement, outlining a detailed plan for race war.” White Power leaders adopted some of the fictional warriors’ key strategies, most notably leaderless resistance, in which small, ostensibly unconnected cells conduct guerilla warfare.

Belew structures her story chronologically, tracking the White Power movement’s evolution through the decades after Vietnam. As she documents, activists like Beam initially saw themselves as helping the government rid the country of Communists and other undesirable aliens. In 1979 and 1980, the Texas Ku Klux Klan (under Beam’s leadership) conducted vigilante border patrols and mounted attacks on Vietnamese fisherman.

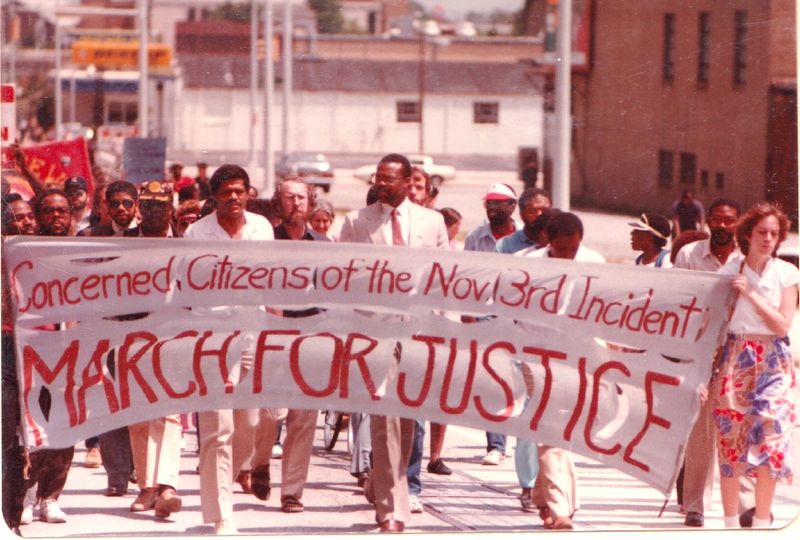

Another early high-profile confrontation took place in Greensboro, NC late in 1979, when Communist Party organizers staged an anti-Klan rally, and Klansman responded by killing five people. Subsequent state and federal trials inaugurated a new level of White Power animosity toward government officials, even as they resulted in acquittals.

By 1983, the movement had fully turned on the federal government. At a July 1983 Aryan Nations Congress in Idaho, activists called for undermining the state through bombings and assassinations. Over the next decade, they engaged in Turner Diaries-style guerilla violence. Meanwhile, the FBI had started to put together a case against the movement as a whole, and in 1989 prosecutors brought more than a dozen people to trial in Fort Smith, AR. Despite a mountain of incriminating evidence, however, all the defendants were acquitted as they had been in Greensboro.

These acquittals emboldened White Power activists; two subsequent flashpoints then embittered them. In 1992, militarized federal agents attempted to arrest white supremacist Randy Weaver on weapons charges at his heavily fortified home in Ruby Ridge, ID. In the standoff that followed, agents shot and killed Weaver’s wife and teenage son. A year later, the FBI and ATF laid siege to a compound in Waco, TX housing a paramilitary religious cult called the Branch Davidians. On April 19, 1993, federal troops stormed the compound, setting it on fire and killing 76 cult members, including 21 children.

For White Power activists, the undeniable federal overreach at Ruby Ridge and Waco constituted nothing less than an opening salvo in the long-anticipated race war. Two years to the day after the Waco debacle, Timothy McVeigh escalated that war.

Belew positions the Oklahoma City bombing as the meeting point of all the threads she has spun. But McVeigh’s prosecution, and the national media’s reporting of it, elided those connections. After its failure to secure convictions at Fort Smith, the FBI abandoned its attempts to link White Power groups together. Instead, they secured McVeigh’s conviction by casting him as a disturbed individual acting mostly on his own.

Belew convincingly argues that the archives tell a different story. As she traces McVeigh’s movements in the days leading up to the bombing, it becomes evident that he was moving within White Power enclaves.

One of the particular strengths of Bring the War Home is Belew’s nuanced analysis of the pivotal role played by women in the movement. In part, that role was symbolic: women represented “innocence, but also future fertility.” But Belew shows how women also played concrete, if supporting, roles. Here again, The Turner Diaries provided a template. Like the fictional narrator’s wife, movement wives wrote newsletters, drove getaway cars, and homeschooled children.

In a tradition going back to populists of an earlier era, their newsletters offered homemaking tips along with exhortations for race war. And in the public sphere, most notably the Fort Smith trial, the presence and demeanor of their wives helped humanize the defendants in the eyes of the judge and jury.

Given the nature of the subject matter, the breadth of Belew’s source base is quite remarkable. She examines a wide array of white supremacist publications, highlighted by an in-depth deconstruction of The Turner Diaries. Mainstream media sources, as well as FBI, ATF, and court records bolster her analysis as well.

She is also a terrific storyteller. The writing is crisp and compulsively readable, marred only by its occasional tendency to overuse conditional verbs. And the story is told so seamlessly that it is easy to keep track of its extensive cast of characters.

The book has one significant omission, but it is deliberate. There are no reproductions of any of the White Power documents that Belew unearthed in the archives. She explains in an introductory note that white supremacist groups still hold most of the copyrights, and she was unwilling to spend any money that might go toward their cause.

In the final analysis, Belew argues that the most important legacy of the Oklahoma City bombing is that it has entered the public memory as an isolated event, providing sustenance to White Power activists even as they went underground, and even as “prolonged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan shaped a new generation [of activists].” But only by confronting White Power as a coherent movement and ideology, shaped by war, can we begin to overcome the legacy of white supremacy and the violence that is its lifeblood.