In his latest book, Peter Brown surveys the ways in which Christians living in Western Europe from 250-650 CE understood the relationship between the living and the dead and how they understood the correct use of money as being instrumental in achieving salvation. Rather than simply providing a narrative survey of all of the sources who speak to these questions, Brown’s focus revolves around why shifts in perspective occurred. His ambition is to show how religious thought is partially shaped, but by no means entirely determined, by changing circumstances in the secular world. Fittingly, since it was none other than Peter Brown who defined the years 250-650 CE as a culturally united timeframe known as “Late Antiquity,” he argues that a total transformation in Christian views occurred in Western Europe over the course of these four centuries.

|

| The Favorites of Emperor Honorius by John William Waterhouse depicts the emperor's court in the 5th century CE. |

Brown argues that in the beginning Christians looked to the “honorable dead” (deceased Christians of high birth) to be their intercessors with the divine. Likewise, they viewed the poor as a nameless, faceless entity upon whom they could lavish alms that would improve their standing in the hereafter. By the mid-7th Century, when the last traces of antiquity had faded from France, Brown shows that the tombstones of the dead requested the prayers of the living, and that the property of the church had come to be thought of as being held as a trust with which to furnish alms to the poor.

Brown’s newest book raises a number of interesting issues and is likely to provoke many thoughtful responses. He does a much better job at laying out the questions and framing issues, however, than he does at providing convincing answers. There can be little doubt that he is correct when he argues that changes in the way that Christians saw the afterlife are a reliable signpost of the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. It is also hard to argue with his assertion that tracing the pace of changes is at least as important as taking note of the changes themselves. Yet, the body of the book does not fully address the issues he raises so eloquently in the introduction.

Perhaps inevitably, Brown’s ambitions required him to dig deep for evidence. As usual, his analysis of the written texts is insightful, at least insofar as he is able to summarize the conclusions of each author in a relatively succinct manner. His use of the material evidence in the form of tombstones, on the other hand, is highly problematic. He is surely right to assume that the initial form and content of these memorials reflects contemporary values. But it becomes more of a stretch when he asks us to share his assumption that the continuation of this form must imply that the people creating these tombstones were accepting the intellectual framework of their forebears. The Romans throughout their history put a high premium on the maintenance of form and tradition, so it is somewhat risky to read much into the repetition of formulaic Latin tombinscriptions over time. Further, it would be a mistake to assume that any given elite burial contemporary with Augustine of Hippo would necessarily adhere to his teachings, or for that matter, even be more than passingly aware of them.

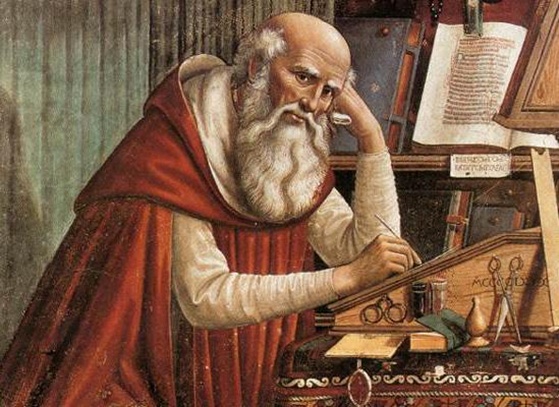

|

| Augustine of Hippo was an early Christian theologian whose writings influenced the development of Western Christianity. |

This, in my opinion, impedes his audience from considering the true centrality of the issues of money and power in religious practice. While a member of the College of Cardinals or the Archbishop of Canterbury might deliver sermons informed by their reading of Tertullian, it is remiss to forget about the way that less recondite modern Christian thinkers, particularly prosperity theologians, try to sell salvation to their flocks. They are, after all, operating within the same tradition and offering a different Christian vision of wealth, poverty, and salvation which many modern Christians accept and adhere to. In contrast to the modern religious leaders who Brown alludes to, it is virtually inconceivable that there is an American televangelist out there who has read any early Christian texts which do not have the words of Christ highlighted in red. Recently, a televangelist with the ironic name Creflo Dollar requested that his congregation raise $70 million dollars so that he could purchase a new Gulfstream jet. At first, it might seem that Reverend Dollar and his teachings are just some garish perversion of regular, decent religious thought. Therein lies one of the faults of Brown’s approach, since he relies entirely on authorial claims without also considering authorial behaviors. Whatever ancient and medieval bishops preached and wrote about poverty, they profited just as much from their relationship with God as Creflo Dollar—they simply spent their money as they saw fit rather than advertising the fact that they were trying to raise money to secure all of the items on their Amazon wish lists.

In his introduction, Brown is emphatic that while this book builds on his 2012 monograph Through the Eye of a Needle, it should not be regarded as a spinoff. However, since that earlier work also focused on the use of wealth during that same time period, it is hard to see a good reason for regarding it as a full departure when his probes into new territories of thought have thus far not panned out. The Ransom of the Soul is not necessarily a failure, but it feels incomplete. However, in the fullness of time it is quite possible that the ambitious introduction of The Ransom of the Soul will provide inspiration to future scholars and father a new vein of historiography in the field. Any work of scholarship which succeeds in provoking thought and conversation should be considered a great contribution.