The early modern period in Britain conjures up images of religious change, civil war, and scientific revolutions. These historical processes gave rise to another phenomenon, however, which would entirely upset the way people interacted with the world. “The decline of magic” occurred after the Reformation of the sixteenth-century and forced a shift from the established Catholic worldview to a new and radical Protestant one. This shift disenchanted the world and separated the secular from the religious, the Scriptural from the traditional.

Michael Hunter, in his book The Decline of Magic: Britain in the Enlightenment, re-examines this transformation from the perspective of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Deists and freethinkers to argue that these skeptical humanists, rather than a monolith called the Scientific Revolution, were the driving forces behind the decline of magic.

Belief in magic and magical occurrences was commonplace before the Reformation and persisted long after the religious upset of the sixteenth-century. For many people, magic helped to explain the relationship between God and the natural world. When the Reformation changed this structured societal order, Protestants attempted to “expel practices that they perceived as magical from the church.”

Historians have called this transformation “the decline of magic” and it has long been a part of the early modern historiographical conversation. Keith Thomas’ 1971 Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-century England stands as the landmark book about this question.

Thomas’s 700-page volume was the first to analyze popular beliefs in magic, witchcraft, omens, sorcery, and astrology. In it, he argued for the centrality of these beliefs to early modern British society. Hunter describes this study as “brilliant” but points to its shortcomings, namely that the book does not explore why the decline of magic happened at the end of the seventeenth century, only that it happened.

Hunter sets out to fill this historiographical hole by adding concepts such as deism and atheism to the conversation. By tracking the freethinking conversations of the early modern British elite, he makes a persuasive argument that magic was not pushed aside by the Scientific Revolution, as previously argued, but rather by skeptics whose views circulated by word-of-mouth.

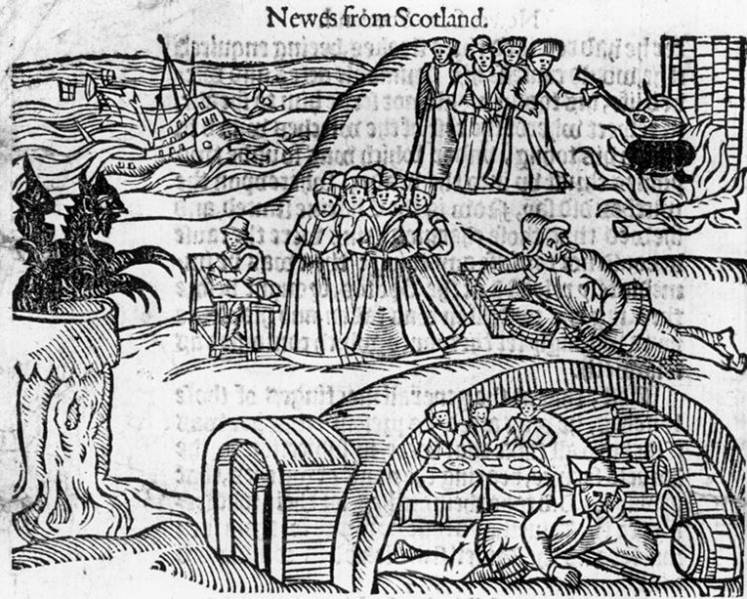

Hunter builds his argument through six chapters, two of which were previously published as essays. He begins the book with an analysis of John Wagstaffe’s The Question of Witchcraft Debated (1669), a work that threw doubt on the accepted existence of witches and contracts between the devil and humans. Hunter is mainly concerned with how Wagstaffe’s book predicts the tone of early eighteenth-century Deists rather than reflects more popular conceptions of witchcraft held in the late seventeenth-century.

The cover the second edition of John Wagstaffe’s The Question of Witchcraft Debated from 1671 (left). A depiction of the burning of Louisa Mabree, a French midwife and convicted witch, in a cage filled with black cats (right).

This leads him to conclude “that comparable ideas [to Wagstaffe’s] may have been more widely expressed in conversation in the Restoration period than is apparent from the printed record.” Hunter’s argument in these first two chapters calls into question commonly accepted arguments that most people believed in witchcraft throughout the early modern period.

The third chapter is where Hunter’s argument comes into sharp focus. Here, he examines the paradoxical role of the early Royal Society in defining magic. Members of the Royal Society never agreed completely on whether magic could explain the natural world and thus the group avoided the question entirely. It was this avoidance of magic that, as Hunter argues, “was constructed as displaying a systemically skeptical attitude, which in practice had never really existed.”

The chapter reveals the significant fissures that existed within scientific circles and gave rise to the argument that the Scientific Revolution brought about magic’s end. Thus, the chapter bolsters Hunter’s larger argument that it was not merely the rise of science that brought about the decline of magic.

A contemporary depiction of the Drummer of Tedworth, 1700.

Chapters 4 and 6 are case studies that round out the book by focusing on popular beliefs in magic throughout Hunter’s chosen period. The first case study encompasses the “Drummer of Tedworth,” a notorious poltergeist that haunted a Wiltshire home in the 1660s. The main take-away from this chapter is that the reality of the poltergeist was never a real issue.

Hunter concludes that “it was a predisposition to believe or to disbelieve, rather than any decisive piece of evidence, that was fundamental in dictating people’s response to what occurred." He uses this “predisposition” several times throughout the book to explain that intellectual change and its stimuli are far more complicated than written sources can reveal. The true transformation comes from generational change and verbal discourse.

Hunter’s book is a welcome addition to the historiography of early modern beliefs and deserves a place among the classics about this period. It is disappointing, however, that Hunter only devotes one chapter to Scottish magic and superstition. While Chapter 6, which focuses on the phenomenon of Second Sight in Scotland, offers a compelling case study for his argument, the Scots had several other more widely held magical beliefs that would have been welcome additions to this study.

A 1754 painting of David Hume (left). David Hume's mausoleum in Edinburgh, Scotland (right, image courtesy of Kristin Osborne).

The Scottish example could have allowed Hunter to add more freethinkers to the analysis. The Scottish Enlightenment, largely overlooked in this volume, produced some of the most notorious freethinkers of the movement, including David Hume and Thomas Brown. Reconciling a highly magical culture with the large intellectual movement of early modern Scotland could have gone a long way toward strengthening Hunter’s argument.

This relatively small criticism does not detract from the importance of this work. It will undoubtedly make an appearance in early modern British colloquia for decades to come. The conversation that it carries on is still wide open for contributions, but Hunter has answered several burning questions about the “decline of magic.”