With The Invisible Bridge, Rick Perlstein—a journalist by profession, but one with a keen eye toward the historical—completes his trilogy chronicling the rise of what has been varyingly referred to as “modern conservatism” or the “New Right.” Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus, the first in the series, won the 2001 Los Angeles Times Book Prize in history, and The New York Times named the second book Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America as a 2008 notable book of the year.

In this newest volume, Perlstein examines a brief period when “America suffered more wounds to its ideal of itself than at just about any other time in its history” (xiii).

The twists and turns along the way are more than worth the ride by anyone interested in high-level politics and intrigue as well as those with a bent toward the cultural side of the dreary—and violent—seventies. And let’s face it: anyone who can keep a reader’s attention in a tome that covers only three years (1973 to 1976) in over 800 pages deserves some kudos. But if you are looking for heroes, this is not the book—or era—for you. And no one comes out looking good at all, liberals and conservatives alike.

Perlstein presents a core dichotomy at the heart of the 1970s American malaise. On the one hand, we see the “suspicious circles,” a group of overly confident, critical, academic, liberal types. Think The New York Times. Think university professors. Think cabernet sauvignon drinkers. These folks, Perlstein writes, mocked and snickered at the backwardness of the emerging conservative movement, those who just didn’t get it. To the circles, Ronald Reagan was a joke, a B-side version of Barry Goldwater.

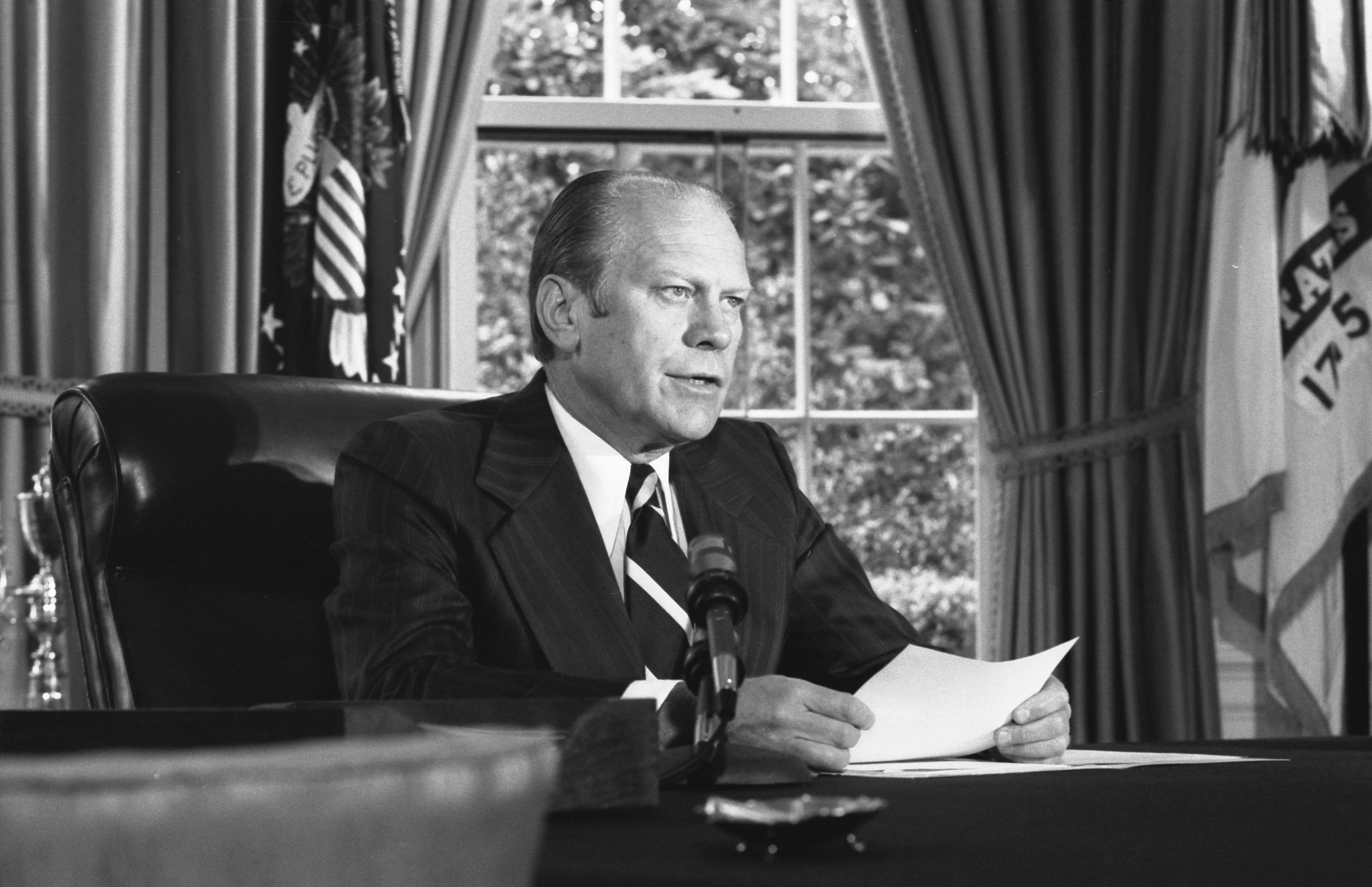

On the other side of the aisle, we track the lurches of an evolving New Right, passionate and confident. Their leader? Certainly not Richard Milhous Nixon, who lost any respect amongst conservatives or liberals alike by the time Gerald Ford hurried to pardon him (pictured left). Nixon did, however, drive the political wedges in as deep as he could. And Ronald Reagan, Perlstein illustrates, was all smiles and optimism and so much more damned likeable than gloomy, paranoid Tricky Dick. Reagan was there to pick up the pieces and, as he saw it, save the day.

And, it seemed, no matter where he went, no matter how many lies or half-truths he uttered, regular people swooned for Reagan (once they learned to say his name right). The man, simply put, had charisma, and as President Ford learned the hard way, there were no political operatives who teach that.

Democrats placed their hopes in the unknown “peanut farmer” Jimmy Carter. Republicans, similarly, almost nominated Reagan, also an unknown to much of the country. Perlstein points out that both candidates shared the same political style and, in some ways, a similar messiah complex. The Democrat from the South mastered what Perlstein calls “the signature Carter straddle” (663), while Reagan never gave a precise answer to just about anything, all while bending the truth to the point of breaking. Their skill at this proved bewildering to their opponents and successful in the political arena—all the more at a low-point in American national confidence.

So despite all the malaise of the seventies—the oil embargo, the crime, the economic slump, the culture of sex and drugs, the decline of the cities, the end of the Vietnam fiasco—Reagan knew, he just knew in his heart of hearts, that the United States of America was great, always had been, and always would be. While the public seemed eager to vote in those anti-establishment politicians known as “Watergate babies” for a fleeting moment, Reagan knew the strongest political play was faith, optimism in the American Dream. Much like the magician-politician in Tim O’Brien’s In the Lake of the Woods, Reagan knew he was destined to invoke this transformation.

Perhaps the most important contribution Perlstein makes is to chart how Americans were able to re-declare their superiority, their exceptionalism, their faith in themselves. While simultaneously answering that need during these years, the Republican Party rapidly transformed into the party of “no”: no to desegregation, no to any separation of church and state, no to the E.R.A., no to détente, no to gun control, no to Roe, no to “handing over” the Panama Canal, no to conceding defeat in Vietnam, no even to admitting Nixon’s criminality. When added together for a growing number of conservative Americans, all these “no’s” equated to a larger collective “yes”—to an idealized image of the nation’s past, something Reagan supporters were reclaiming through their staunch opposition. And that was more than enough as it is today for many conservative voters like the Tea Party.

As the Bicentennial approached in 1976, “people yearned to believe” (709). On the cultural front, this meant banishing thoughts of The Exorcist and Taxi Driver, the travails of Patty Hearst (right) and the implosion of New York City. Instead, the country embraced the wholesomeness they knew represented the best of the nation. Carter and Reagan were the candidates to help achieve that. It was just that one of them had to overcome too much to rise to the highest office in the land.

And if all these themes aren’t enough to convince you to go out and read The Invisible Bridge, the political play-by-play is worth it alone. The narrative of John Sears’ choice of V.P. for Reagan is nothing short of astonishing. It reminds us why The West Wing was so much fun.

But nobody wins here. America’s highest ideals are not on display. Jimmy Carter suspiciously finds that old-time religion just in time to run for national office. And the burgeoning conservative movement finds its greatest strength not in the ideals of moderation and charity, but in the wedge issues of busing, school prayer, and P.O.W.s—issues that Nixon highlighted so expertly.

While admirable from one angle, Perlstein has a tendency to be overly-evenhanded. By the end, everyone is so suspect and sleazy, that the reader is left to wonder what was the point of it all? The suspicious circles are smug and foolish, filled with hubris. Grassroots conservatives are also too sure of themselves, too eager to “reclaim” their America (sound familiar?). Jimmy Carter lied, was egotistical, and waffled on issues from civil rights to foreign policy. So did Ronald Reagan. So did Gerald Ford (although with a bit more physical fumbling). This tends to undercut the thrust of the book: a sense of anti-climax settles over the proceedings, even as the anecdotes and narrative still engage and, at times, thrill.

Perlstein offers us a couple of somber reminders: in politics, all too often, the candidates are narcissistic liars, and everyone has an agenda to push. There are no heroes here, Perlstein tells us, and history isn’t necessarily supposed to make us feel good about ourselves.