In 1957, Abraham Johannes (A.J.) Muste sat down to write his autobiography. Had he finished it, the book undoubtedly would have been filled with the friends and acquaintances he made among the various workers, intellectuals, preachers, activists, sinners, and saints whom he had met over the seventy-two years that he spent on Earth. It would have told the story of a Calvinist intellectual preacher who transformed into a revolutionary labor leader, before finally transforming into a radical prophet of Christian pacifism. But he never finished the book. Muste was a busy man, and there was always a world that needed redeeming. When he died ten years later, scores of mourners, from New York to Tanzania to Hanoi, hailed the loss of one of the brightest minds and most tireless spirits that had animated the nonconformist left. Historian Leilah Danielson attempts to complete the work that Muste did not.

It is most useful to see Danielson's story as an intellectual history disguised as biography. Muste blended Christian idealism with a pragmatism born out of the experience of an activist. As his thought evolved during his long life, he also developed an almost prophetic vision of a peaceful Christian world. Danielson, importantly, also uses Muste's story as a lens on the (mostly radical) left from early 20th century progressives through the anti-war “New Left” of the 1960's.

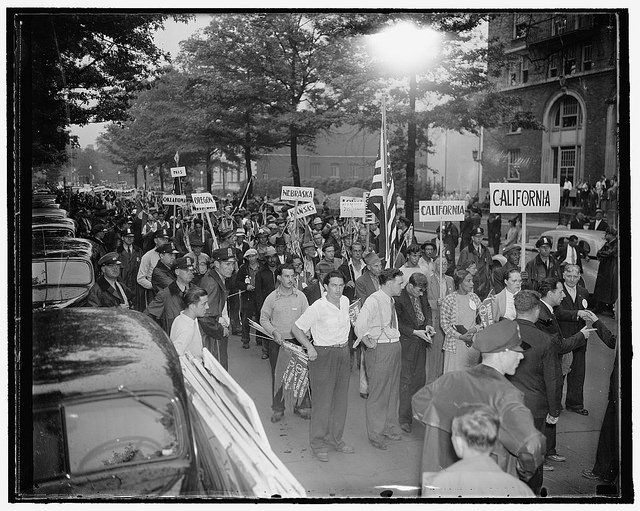

After being forced out of his pastorate during the First World War because of his pacifist beliefs, Muste entered the labor movement armed with the belief that it held the revolutionary potential to overthrow capitalism and usher in a era of world peace. In doing so, he tried to forge an independent middle ground between the Communists on the left and the AFL on the right, first at Brookwood Labor College, then within the Conference for Progressive Labor Action, his own radical education/activist organization. The middle ground that Muste tried to hold collapsed by the mid-30's and the Communists took over much of the revolutionary left. By this time, the mainstream labor movement had formed the activist core of the Democratic Party's emerging New Deal coalition.

|

| A.J. Muste poses for a photograph in 1931 |

In joining with the Democrats – the party of Jim Crow and militarism according to Muste – labor had shackled itself to racist capitalism and surrendered to militaristic nationalism. By 1936, Muste left the labor movement behind and with reconnect with his pacifist Christian roots.It is most useful to see Danielson's story as an intellectual history disguised as biography. Muste blended Christian idealism with a pragmatism born out of the experience of an activist. As his thought evolved during his long life, he also developed an almost prophetic vision of a peaceful Christian world. Danielson, importantly, also uses Muste's story as a lens on the (mostly radical) left from early 20th century progressives through the anti-war “New Left” of the 1960's.

The 1950's proved to be a time of renewed intellectual flowering and activism for Muste. He believed that liberalism, as embodied by the New Deal order, had failed precisely because it had bolstered global capitalism and created the military-industrial complex. The solution for Muste lay in an escape from liberal institutionalism, in direct non-violent actions by cells of individuals in lieu of the masses. It was here that Muste's thought began to prefigure much of the same critique that the New Left would make famous in the 1960's. The onset of the Vietnam War marked the capstone of Muste's global vision, and it would be somewhat of an obsession for the remainder of his life. In his view, the United States was leveraging its massive military superiority in a racist colonial war to oppress the people of North Vietnam. He would spend the last few years of his life trying to build a broad coalition of activists against the war, even traveling to Hanoi and meeting Ho Chi Minh.

The Second World War and, especially, the use of atomic weaponry at the end of it, seem to have ignited the prophetic tradition of Christianity in Muste. While he would never fully abandon the struggle against capitalism, his attention clearly turned toward anti-war/military/nuclear activism. Danielson argues that the emerging Cold War, global de-colonization struggles, and the American civil rights movement all crystallized into a single pacifist struggle against racist, violent nation-states, and the racist, violent American state, in particular.

Given how often Muste served in a leadership role in various organizations, Danielson seems well-grounded in her assertion that his intellect and spirit awed and inspired his friends and acquaintances. Indeed, the high rate of eventual collapse among his projects and the inability of his ideas to make an impact on the establishment make his determination and sunny disposition seem quite remarkable. We know that he had a strong relationship with his parents, siblings, wife, and children. But these relationships take a back seat to the story of Muste's ideas and activism, an aspect of Danielson's reckoning that appears to mirror the realities of Mustes life. This is most evident in his relationship with his wife, Annie, whose homemaking and childrearing labor Muste appears to have taken for granted despite his otherwise radical politics. Annie did not seem to share her husband's zeal for remaking the world, and his constant moving around and activism ultimately took a toll on her health as the family was whisked from place to place.

Danielson traces Muste's participation in a veritable laundry list of leftist organizations: the Amalgamated Textile Workers, ACLU, Brookwood, Fellowship of Reconciliation, SANE, the Peacemakers, and MOBE to only name a few. Likewise, Muste seems to have corresponded with members of the Old Left and New and seemingly everyone in between, from Norman Thomas and Sidney Hook to Tom Hayden and Bayard Rustin. In this sense, Muste's own life in activism provides the reader with a first-hand account of just how fractious the pre-New Deal labor movement was; or how the monstrous violence of the atomic age could drive the alienation of the New Left.

Danielson is at her best in the last chapters detailing Muste's increasing horror as he understood the United States emerging role a global force of violence and domination, perhaps even an existential threat to the world itself. The revolutionary potential of labor had been co-opted by a Democratic Party that was just as eager as the Republicans to build a national security state with an endless reach. America had sacrificed its soul, even as it achieved unparalleled economic and military superiority.

|

| Close-up of the mural commemorating works of A.J. Muste on the War Resisters League Building in New York, New York. |

His penetrating analysis of what Eisenhower would term the “military-industrial complex” was even more prescient than he knew. As the Cold War gave way to the War on Terror, Americans have confronted the possibility of seemingly endless war. Muste would have seen the killing power of predator drones and the savage torture techniques of CIA interrogators not as accidents or regretful necessities in the long war to make the world safe for democracy, but as the logical, perhaps inevitable culmination of the “American Century.”

One of Danielson's last anecdotes is of an elderly Afghanistan/Iraq War protester who was asked in 2010 if she really thought that her demonstration in front of Rockefeller Center would have any impact on American policy. She quoted Muste, who was asked a similar question while demonstrating against Vietnam in front of the White House: “I don't do this to change the country, I do this so the country won't change me” (336). Almost fifty years after Muste's death, Americans seem no closer to finding the way to peace.