Prost! This year marks the 500-year anniversary of a decree that became the famed German Reinheitsgebot, or beer purity law.

Originally a somewhat mundane trade regulation law, the Reinheitsgebot is today lauded as an early food safety regulation. And, as beer-making elsewhere has taken off in all sorts of different, dynamic directions, Bavarian brewers celebrate the law as a sign of centuries of quality and tradition.

|

|

Water, barley (left) and hops (right) are the acceptable ingredients in beer according to the Reinheitsgebot.

Half a millennium ago, in 1516, Dukes Wilhelm IV and Ludwig X of Ingolstadt, a city in present-day Bavaria, limited the acceptable ingredients in beer to “barley, hops, and water.” At the time, a growing taste for the pale and crisp styles of beer produced by adding wheat to the brewer’s grist had been driving up prices for bread. The decree sought to standardize the price of beer per Maß (a Bavarian liter) and to limit competition for cereal grains used to bake bread.

|

| A traditional glass of Weissbier |

But an aristocratic taste for wheat beer (Weissbier or Hefeweizen) survived in spite of the ban on wheat in commercial and private production. The Duke of Wittelsbach, for instance, mandated a single brewery in the village of Schwarnach to produce the coveted Weissbier.

Today, beer drinkers like to point out that the decree was innocent of knowledge of yeast and fermentation—revealed by the work of Louis Pasteur in the 1850s. While Pasteur’s discovery was revolutionary in the understanding of beer and fermentation, historical studies of brewing have found methods of preserving, drying, and pitching what we now know as yeast used in brewers guilds as early as the 1400s.

Prior to the twentieth century, people simply referred to the 1516 law as the Surrogateverbot—a name that captured the law’s intended purpose in preventing the use of adjuncts and surrogates in brewing. In 1871, the decreefound its place as part of the tax code of a newly unified Germany.

A member of the Bavarian parliament coined the term “Reinheitsgebot” in 1918 during a discussion of the law’s application in the new German Weimar Republic. After the 1949 division of Germany into East and West states, it continued to apply to West Germany, but not to breweries in the socialist East during the forty years that the Democratic Republic of Germany existed.

By the 1980s, the growing availability of large multinational beer brands like Heineken and Carlsberg began to challenge the West German preference for traditional, local brands. And after allegations by French brewers that the Reinheitsgebot was protectionist, the European Union struck down the law as an impediment to free trade in 1987. Because the ruling only applied to imported beer, Germany continued to enforce the law domestically and Bavarian brewers continued to follow their traditions with pride.

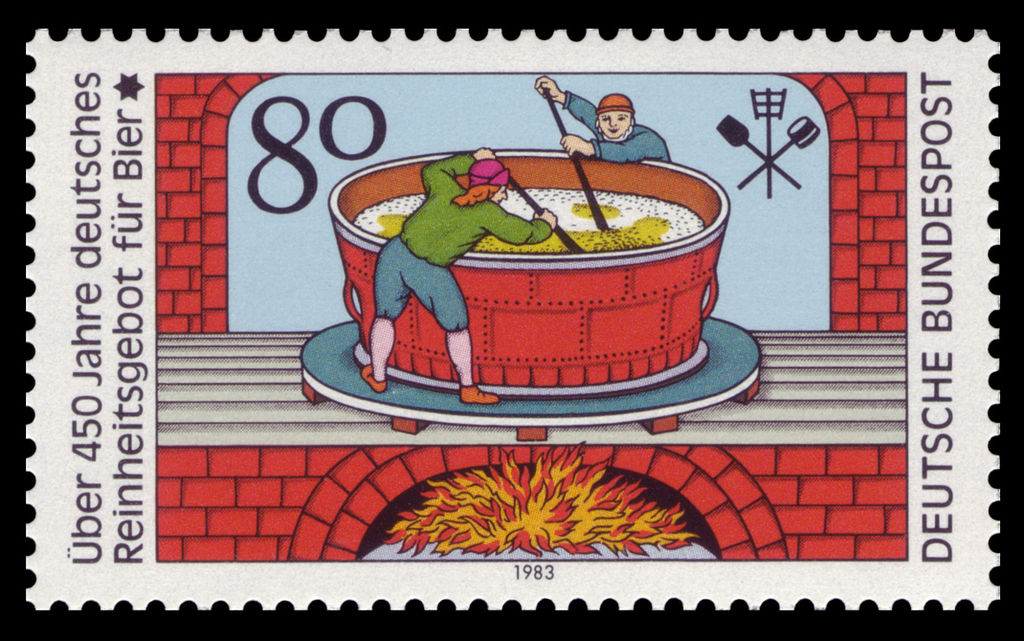

1983 Reinheitsgebot commemorative stamp

In today’s reunified Germany, a new generation of beer drinkers drinks less beer than their parents and challenges tradition with an ever-increasing taste for imported non-Reinheitsgebot styles of beer. Bavarian beers now compete on an international stage—one of the United States’ largest craft breweries, Stone, recently opened a brewery in Germany.

Still, just a few blocks away from the site of Munich’s famous Oktoberfest beer festival, Sead Husic’s photo exhibition at the Alte Kongresshalle, “Die Wächter des Reinheitsgebotes” (The Watchers of the Reinheitsgebot), celebrates Bavaria’s world-famous tradition. On the opening day of the exhibition in February of 2016, Munich’s Deputy Mayor, Josef Schmid, credited the Reinheitsgebot for establishing a high standard for Bavaria’s breweries.

In Munich, beer purity laws are as old as the city’s identity. In another speech at the exhibitions opening, Friedrich Düll, head of the Bavarian Brewer’s Association, drew attention to city ordinances in Munich that predate the Reinheitsgebot—decrees with respect to regulating beer quality that date as far back as 1363.

|

| 2016 Reinheitsgebot commemorative stamp |

The Reinheitsgebot, as any other Bavarian tradition, belongs to Bavaria. More than defining what beer is, the law represents one small snapshot in the rich history of the world’s favorite drink. In 2013 the German Brewers’ Association even petitioned to add the law to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

But while the Bavarians proudly point to their tradition as one of the oldest existing food purity laws, the World Health Organization has questioned whether this tradition stands up to modern standards. A study earlier this year found glyphosate herbicide present in several major German brands. The German brewers have dismissed the findings as negligible.

All over the world, beer has been made from all types of different grains and infused with a wide range of tastes. Belgians have proudly added spices to their beers for centuries—a practice forbidden in Bavaria. In the United States, everything from coffee to cannabis has been added to this popular drink.

New trends and economic pressures continue to shape new tastes and different interpretations of beer.

In Africa, major beer brands like SABMiller and their subsidiary, Nile Breweries, first began to experiment with local staples in beer in the early 2000s. A sorghum beer named Eagle, developed as a way to lessen the challenge of high barley prices and to help with brewers’ margins, enjoys a large market share in Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In countries such as Mozambique and Southern Sudan, adopting cassava in the brewing process reflects local tastes and ingredients.