“Divide and Rule” was the motto of British colonialism in India. 1919 saw a classic example of this policy in action when hundreds of unarmed, peaceful civilians in Punjab were shot by British soldiers under the command of the now infamous “Butcher of Amritsar.”

British colonial reforms in 1919 endeavored to “reward” the people of India for their participation in World War I by allowing more Indians in governance. Still, wartime measures to suppress civil liberties were kept in place. Known as the Rowlatt Acts, these measures ensured that police and armed forces could continue to imprison Indians without trial, suspend habeas corpus, and enforce prohibitions on public gatherings.

In this way, the British Raj could take credit for bringing democracy to India while cracking down on political dissent.

Indian troops played many roles in the service of the British Empire in World War I; here, Indian bicycle troops are pictured at the Somme in 1916.

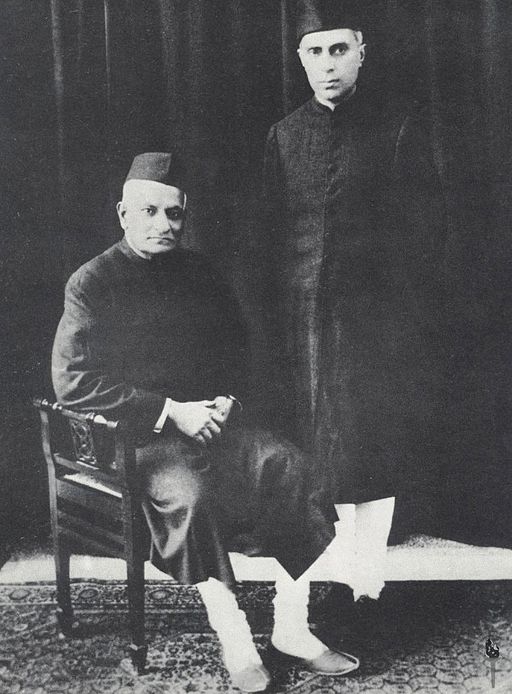

The Rowlatt Acts outraged the Indian National Congress, the leading nationalist party whose members included Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Motilal Nehru and his son Jawaharlal, and a man who would soon become very well known—Mohandas K. Gandhi.

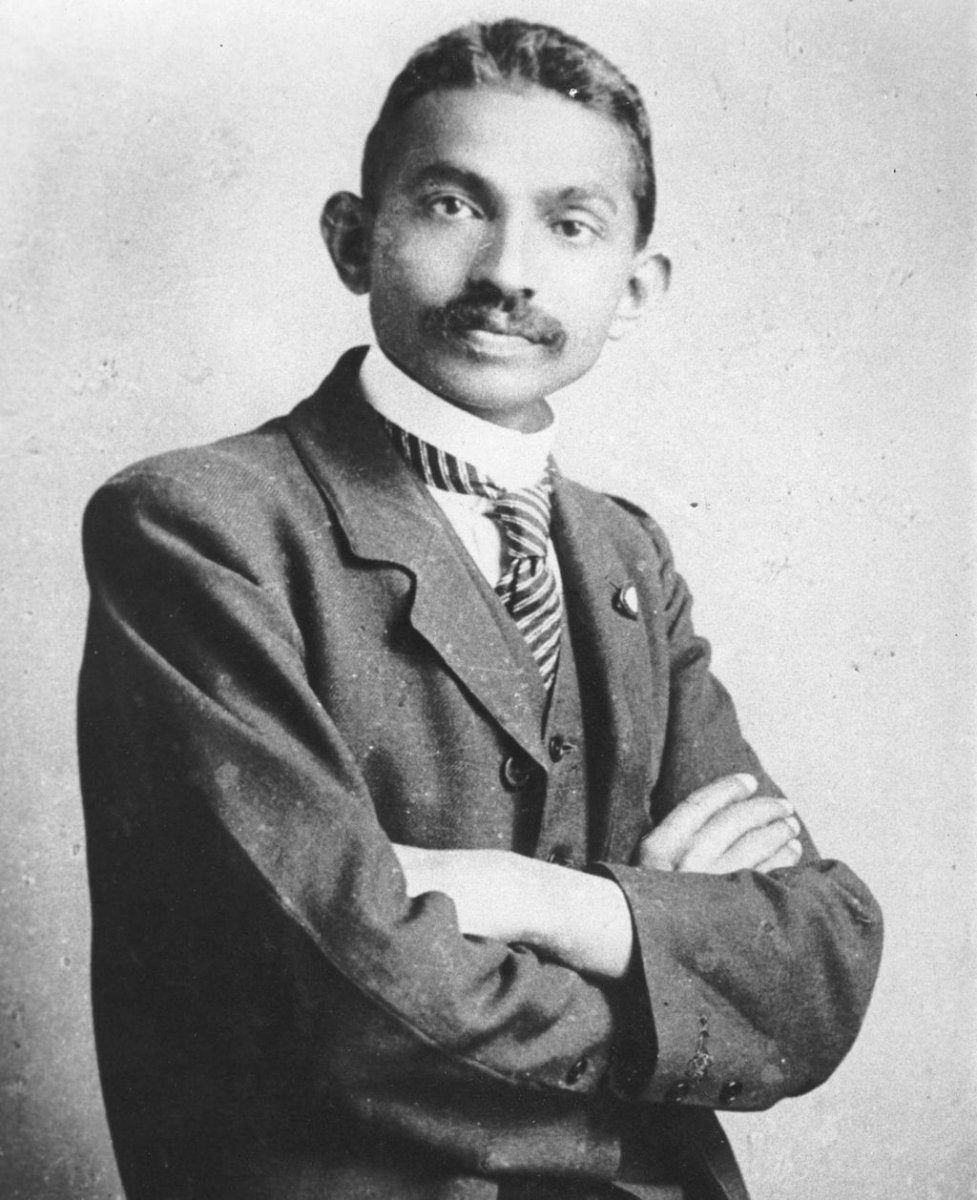

In 1919, Gandhi was fresh from his sojourn in South Africa and hoping to demonstrate India’s readiness for Dominion status within an Empire that he believed inherently just. The Rowlatt Acts and what would follow shook the faith of the Congress leadership. Were the institutions of the British Raj as honorable as Gandhi believed?

Ironically, Congress’s reaction to the Rowlatt Acts mirrored some British reactions to the 1919 reforms. For instance, Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab, believed that the British were the rightful rulers of India. He was also seriously worried about the unprecedented unity between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in Punjab at the time.

In 1919, Mohandas Gandhi had recently returned to India from South Africa–where he is pictured here in 1906–to advocate on behalf of Dominion status for India.

Consequently, he enforced the Rowlatt Acts more stringently in Punjab than in any other province. Indian leaders who might give anti-Rowlatt speeches were summarily arrested. The slightest hint of anti-British sentiment was met with repression. Gandhi was banned from entering the province.

British paranoia and Indian indignation rose to a fever pitch.

Matters came to a head on April 13 in Jallianwala Bagh, a square near the Sikh Golden Temple of Amritsar.

In protest of the Rowlatt Acts, protestors gathered in a square near the Sikh Golden Temple of Amritsar–pictured here in 1880.

A small political gathering had attracted a larger crowd than was expected. It was the festival of Baisakhi and many had come to relax in the square after offering prayers at the Golden Temple.

Colonel Reginald Dyer, an “old India hand,” who was born and raised in the subcontinent, led a group of Gurkha, Baluch, and Pathan soldiers towards the square. Dyer and his men faced a slight setback when the Colonel realized his armored car (complete with machine gun) was too wide to enter the narrow passageway into the square (at most only four people can walk abreast).

Forsaking the car, Dyer’s men entered the square and assembled into formation. Without any warning, Dyer gave the order to fire into the unarmed, non-violent crowd.

The passageway to Jallianwala Bagh square.

As men, women, and children began to run in terror Dyer ordered his men to continue firing into the thickest part of the crowd. People began to jump into the square’s well in order to save themselves. Most of them drowned or suffocated under the weight of others jumping in after them.

The firing did not stop until the soldiers exhausted their ammunition: 1,650 rounds. The numbers of wounded and dead are still unknown. Early estimates ranged from 291 dead (British officials) to 1000 (Congress report).

After the massacre, Dyer, the “Butcher of Amritsar,” strolled back to his car and made his way back to the military camp.

So desperate was the situation that victims began jumping into what is now called Martyr’s Well, in the Jallianwala Campus area, when the shooting started.

The response to the Amritsar Massacre was varied.

Congress set up a committee to inquire into the massacre as well as the ensuing atrocities perpetrated by Dyer and O’Dwyer.

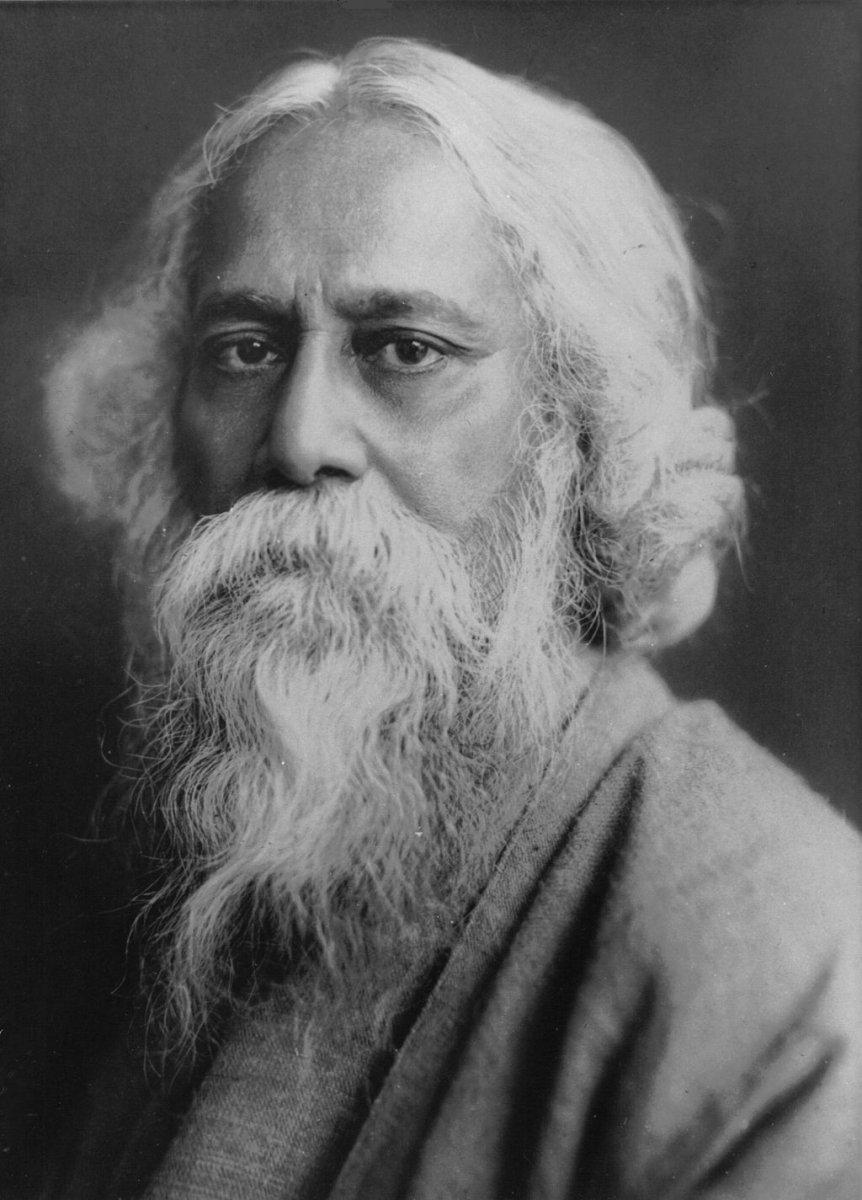

Indian Nobel laureate and “bard of Bengal” Rabindranath Tagore renounced his knighthood, noting, “the accounts of the insults and sufferings of our brothers in Punjab have trickled through the gagged silence, reaching every corner of India, and the universal agony of indignation roused in our hearts has been ignored by our rulers—possibly congratulating themselves for imparting what they imagine as salutary lessons.”

Rabindranath Tagore, a Nobel laureate known as the “bard of Bengal,” renounced his knighthood, accusing authorities of purposely covering up and refusing to respond to the Amritsar Massacre.

Tagore was quite right. O’Dwyer did not investigate. Rudyard Kipling told the world that Dyer “did his duty as he saw it.”

It was only in October that the Hunter Commission (comprised of British and Indian men) formed to inquire into violence in Punjab.

Dyer testified that the moral lesson imparted at Amritsar far outweighed any loss of human life. As he put it, “I thought I would be doing a jolly lot of good and [Indians] would realize that they were not to be wicked.” His only regret was running out of ammunition.

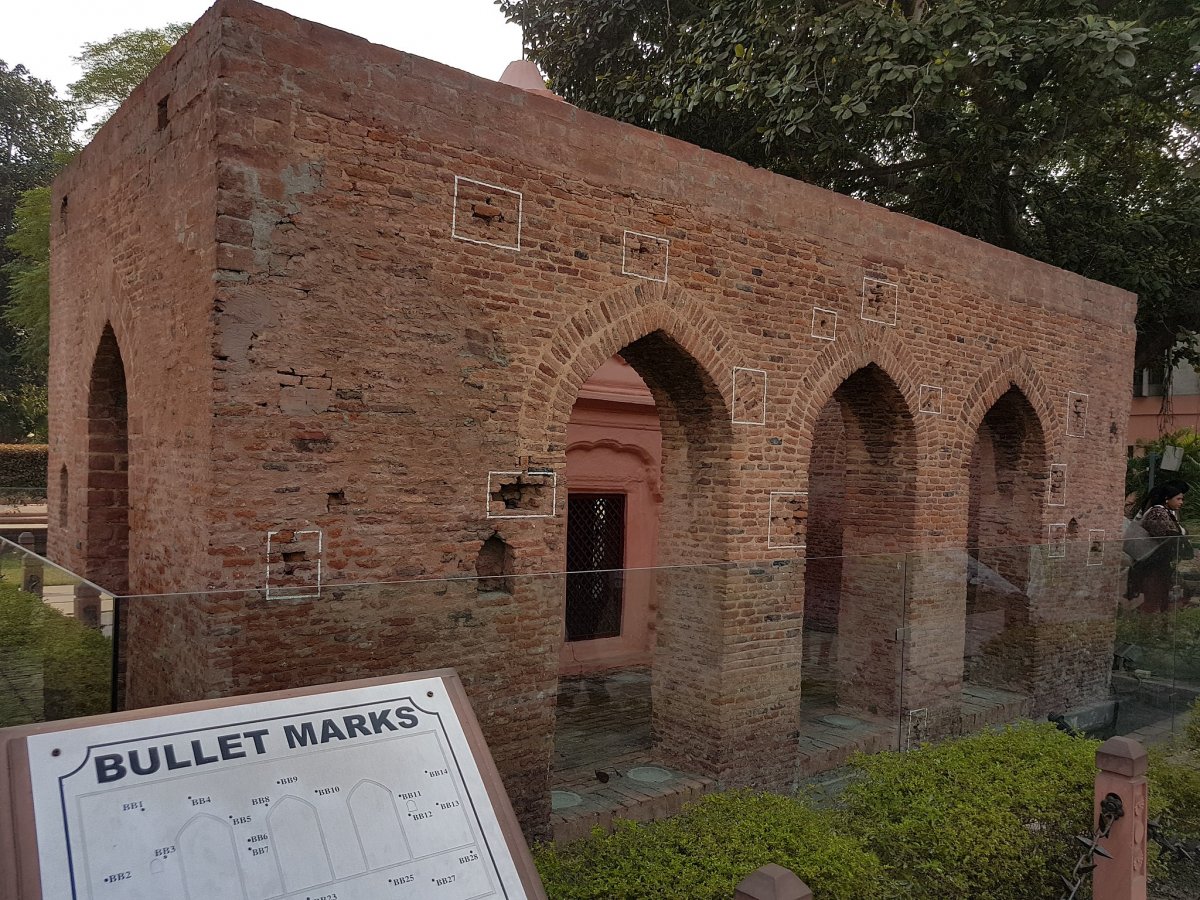

Bullet holes from the rounds fired by Dyer’s troops in 1919.

Dyer continued to believe that he was the “savior of India” until he died, and he was not alone. While the Hunter Commission and the United Kingdom’s House of Commons recommended his immediate dismissal, the House of Lords was more lenient.

The British press had mixed responses, but The Morning Post hailed Dyer as the man who saved India, starting a subscription to collect funds for him and his wife to live out retirement in England. The subscription yielded a princely £28,000, of which nearly £9,000 was donated by British in India.

The massacre and continued police brutality in its aftermath was a turning point in Indian anti-colonialism.

Motilal and Jawaharlal Nehru were prominent members of the early Indian National Congress; the Amritsar Massacre radicalized nationalists such as the Nehrus and led them to question whether India could ever be a British Dominion, and should instead push for independence.

Before 1919, the Congress Party’s activities focused on increasing representation for Indians in governance, and eventual Dominion status—an amicable parting from direct British rule. As Dyer was exonerated and valorized, Indian leaders realized that this was no longer possible.

Udham Singh, who survived the massacre, saw it as his destiny to take revenge on those he held responsible. Nearly twenty years after the event, he assassinated O’Dwyer. At his trial, he was unapologetic, “for full 21 years, I have been trying to seek vengeance…I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. What greater honor could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?” Singh was condemned to death.

Udham Singh, a survivor of the massacre, is led away by authorities after assassinating the Michael O'Dwyer, the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre, years later in 1941.

Dyer’s reception in India and England exposed the hypocrisy of the British Raj, especially for Gandhi. Writing to Viceroy Chelmsford in 1920, he was furious: “your shameful ignorance of the Punjab events and callous disregard of the feelings betrayed by the House of Lords . . . have estranged me completely from the present government and have disabled me from tendering, as I have hitherto tendered, my loyal cooperation.”

The loss of Gandhi’s cooperation was not to be taken lightly, as he went on to popularize a method of anti-colonialism that rested on mass non-cooperation and civil disobedience. His philosophy of non-violence was hailed globally, and he is remembered today in India as the man who led a country to freedom—the “Father of the Nation.”

The Amritsar Massacre one hundred years ago can be seen as the beginning of the end of British rule in India.

Memorial dedicated to the victims of the massacre.