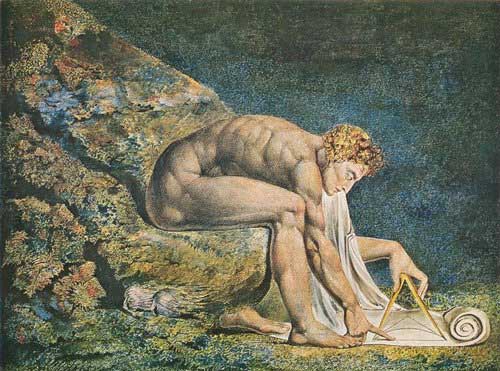

On December 25, 2012, we celebrate Isaac Newton’s 370th birthday. On one hand, the man popularly famous for getting hit on the head with an apple could probably think of better birthday presents than the Higgs Boson, or “God Particle,” which might challenge the very foundations of Newtonian physics. On the other hand, Newton also claimed to have seen further than others only because he stood on the shoulders of giants, so perhaps he’d welcome the gift.

Newton is famous for Principia Mathematica (1687), the weighty tome which laid out the three laws of motion—inertia, action and reaction, and acceleration. His research helped legitimate the scientific method and, eventually, led to huge strides in technology. Newton’s theories have proven excellent at describing the movement of atoms, setting the foundation for modern physical sciences until Albert Einstein’s 1905 Special Theory of Relativity and 1915 General Theory of Relativity showed that Newton’s laws collapsed at near-light speed or in stronger gravitational fields than Earth’s. Enter the boson, a particle that obeys quantum rather than Newtonian laws.

Newton’s laws still work for us here on Earth in day-to-day matters. But just as Einstein refined Newton, so Higgs has refined Einstein. The Higgs quantum field allows physicists’ mathematical equations to maintain their symmetry. Perhaps the best analogy is one of a Hollywood party described by the Exploratorium here. Or, to tailor your explanations to various audiences, try this hilarious guide from The Guardian.

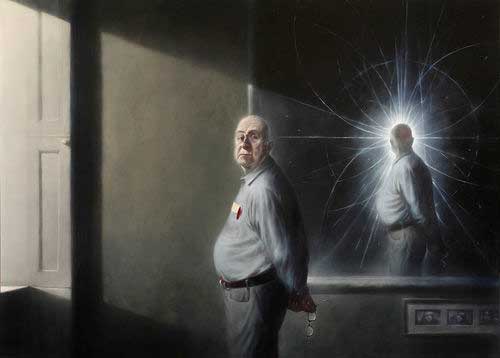

Most physicists rue the Higgs Boson’s nickname “God particle,” popularized by Leon Lederman in a 1993 book (although he claims the publisher came up with the name). Peter Higgs, who, along with others, proposed the existence of the particle in 1964, is an atheist who dislikes the term because he worries it will offend the religious. Other scientists say that, although the Higgs Boson is essential in pushing particle-physics theory forward, the nickname gives it too much credit.

Newton, too, aimed to keep God out of his explanations for the physical laws of the universe. His first edition of the Principia made no mention at all of God, but he was urged by some contemporaries to add passages on God’s place in his natural philosophy, in order to refute those who had accused him of disbelief by omitting God from his explanation of a world system. The second edition, 26 years after the first, described a God that had created, ordered, and continued to contain the universe, but who did not run it on a day-to-day basis. “In him are all things contained and moved,” he wrote, “yet neither affects the other: God suffers nothing from the motion of bodies; bodies find no resistance from the omnipresence of God.” Newton did not see God as necessary for explaining physical laws, but as a “First Cause” of them. Thus Newton separated his explanations of how the universe worked—according to laws—and how it came to be—through a divine creator.

Einstein’s thoughts on God were remarkably similar. Although he had rejected his Jewish religious training around age 12, Einstein always maintained that reverence for the “mysterious”—for the unknowable in nature—constituted a religious outlook. He disparaged those that used his words to bolster the attraction of atheism. “Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that, behind all the discernible laws and connections, there remains something subtle, intangible and inexplicable,” he said. “Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion.”