One hundred and fifty years ago, this July 1, three British colonies stretching from the western edge of Lake Erie to Nova Scotia signed an agreement to confederate into the Dominion of Canada. Preparations for the celebration of this anniversary have been branded “Canada 150” and packaged with a beautiful line drawing of a maple leaf worked in multi-coloured diamond shapes.

This evocative image birthed another: the same line image, but all in black, upside down, and tagged “Colonialism 150.” This is the trouble with a national anniversary in a colonial state: it brings the state’s origins into sharp focus and reveals who is left out of its benefits. Even as it invites celebration it forces a reckoning.

Logo for "Canada 150" (left), and the design for "Colonialism 150" by Eric Ritskes (right).

First Nation leaders from Métis artist Christi Belcourt to Anishinaabe comedian Ryan McMahon have pointed out that the past 150 years have been the worst in their history. The country was built on the theft of indigenous lands. Canadian rule has visited the violence of the residential schools, a sustained attack on subsistence systems, and a federally imposed dismantling of traditional governance structures upon the original caretakers of the land.

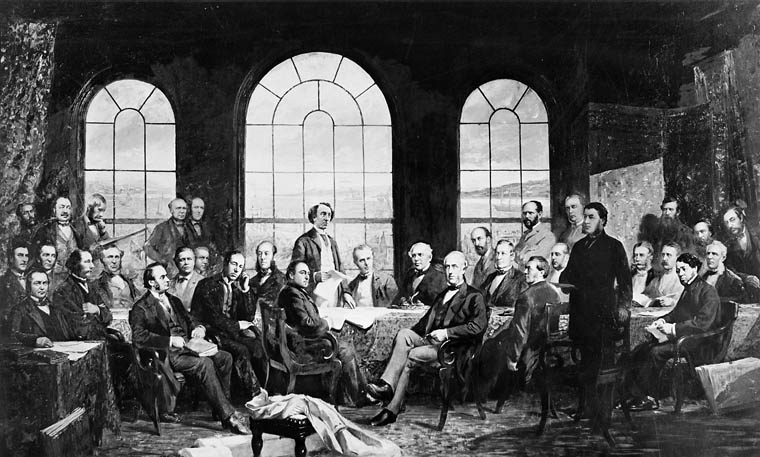

Depiction of negotiations leading to the British North America Act of 1867.

A mere 9 years after the 1867 signing of confederation Canada passed “The Indian Act,” a separate and not equal form of government especially for First Nations. The Indian Act remains in place today, confining and constraining Indigenous jurisdiction in every area of life, in direct contravention of the nation’s founding treaties with indigenous nations.

Front and back of the Indian Chiefs Medal, commemorating Treaties 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

Canada’s inability to own up to, end, and make reparations for, our colonial violence arises in part from the dissonance between the scale and ferocity of those crimes and many Canadians’ most basic understanding of ourselves. Each new act of violence is immediately wrapped in the cloak of exceptionalism, regardless of how predictable it may have been from any perspective but our own.

The country’s proximity to the United States has invited moral comparisons since its very inception: a peaceful confederation as opposed to a violent revolution. It has been strategic for Canadian politicians and the American left to elevate and exaggerate the country’s progressive values for their own ends and we have become puffed up by their praises.

David Laird explaining the terms of Treaty #8 at Fort Vermilion, 1899.

If orators have been able to return to that well for over a century, it is because it was not entirely dry. Canada has avoided the extremes of income and regional inequality that have plagued the US and did so through a series of political choices that systemically privileged regional economic equality: a plain Jane set of policies with wide reaching social justice consequences.

Confederation gave the federal government the lion’s share of taxing authority and assigned the administration of social programmes to the provinces. The federal government divides funding to ensure roughly equal levels of social services across the country, regardless of each provinces’ tax contribution. This initial wealth redistribution system was augmented in the mid twentieth century by an equalization programme to help the struggling Maritime Provinces. The net result is a basic national standard for schools, infrastructure, arts, and health care.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth meet with Nakoda chieftains in Calgary, 1939.

More equitable funding ensures rough equality of schools across most of the country. Socialized medicine frees families from living with untreated illnesses and bankruptcies. Canadians’ unified response to the Syrian refugee crisis was made possible by a political system less polarized than those in states more divided by economic differences.

Just Us! sign advertising Canada 150.

However, even here in our A-game, Canada’s transfer payments are bested by the European Union’s Regional Policy that dedicates a full one third of EU wealth to the structural economic rehabilitation of poor regions. No less than 92 countries around the globe have broken free from political polarization by adopting proportional representation.

And none of this equality has extended to those who most deserve to benefit from the nation’s wealth: the First Nations. Social programs on reserves have less funding than comparable programs in the rest of the country. One hundred and forty reserves have contaminated water flowing from their taps; school buildings on reserves are in disrepair, some infested with mold and snakes; First Nation people have unequal access to justice and face far more violence than settler Canadians, and they have reduced access to health care.

Despite a century and a half of reassurance from historians and journalists and statesmen that we are uniquely decent people, many Canadians do see our injustice toward our treaty partners quite plainly. In 1990 the Canadian government ordered a Royal Commission on Aboriginal People, “RCAP.” One of the RCAP commissioners, the Dene leader Georges Erasmus, has said that all through his work as an advocate for First Nations he noticed the strong support of the Canadian people.

Dene leader Georges Henry Erasmus (Photo CBC).

It may be that a growing number of Canadians are indeed ready to search for self understanding, not in media spin and nationalist clichés, but in the sterner judgments of the First Nation people we live beside, and the land that supports us all.

Maybe this shouldn’t be a 150th anniversary after all, but instead, the birthday of a new kind of Canadian who, in humility and hope, turns away from the flattery of the world and toward the place they call home, and the people who await them there.