In 2018, the Canadian $10 bill had a new face. Viola Irene (Davis) Desmond, replaced John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first prime minister, who had been on the note since 1971. How Desmond became the first woman in Canadian history to grace the $10 bill, a Black woman no less, requires returning to the events of Friday, November 8, 1946.

The new $10 Canadian dollar bill featuring Viola Desmond.

On that day, Desmond became the target of a racist incident, a common event for Blacks in Canada.

Her decision to challenge what could have simply been another daily injustice catapulted her into the limelight, ultimately making her the reluctant face of Canada’s Civil Rights struggle. Her story reminds us not only of the past—and present—of anti-Black racism in Canada, but also of the heroism and dignity with which Black Canadians stood up to racial segregation.

Desmond was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia on July 6, 1914, into a middle-class Black (mixed-race) family whose ancestors had been in Canada for generations. She attended a racially mixed high school and was an outstanding student. Desmond aspired to be a teacher, a choice of career that reflected the prevailing gender ideas that women had a natural propensity for teaching.

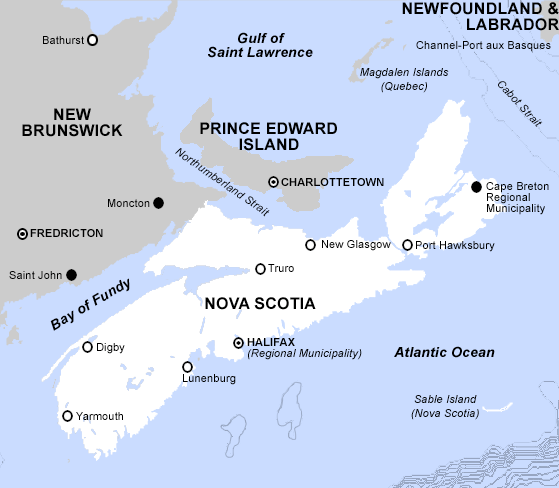

Map showing the location of Halifax and New Glasgow, Nova Scotia.

Although Blacks were prohibited from teacher education programs, Desmond earned a teacher’s certificate by completing a provincial test. She was required to teach in a segregated Black school, which she did in Upper Hammonds Plain and Preston, two predominantly Black communities in Halifax.

Desmond and her students were the descendants of either Black Loyalists who chose to fight on the side of the British, refugees who escaped slavery, or free Blacks who made their way to Canada from the United States. Touted as the “Promised Land,” Canada offered freedom from U.S. enslavement and other oppressive practices.

But freedom came at a price. The new arrivals soon discovered that racism was as much a Canadian phenomenon as it was American.

Black Canadians pose with Ontario Premier Ernest Charles Drury, 1920.

Although no consistent pattern existed across Canada, as a group, Black Canadians were abysmally affected by established legal ordinances, which prohibited them from owning land and buying homes.

They also faced discrimination in areas of public life. Blacks were barred from jury service, places of worship, and refused service by some hospitals. Blacks and whites sat in separate sections at theatres. Motels, hotels, taverns, and restaurants routinely denied service to Blacks.

Excluded from white institutions, Black Canadians created their own schools, churches, community organizations, and businesses. Coming from a long line of barbers, Desmond wanted to own a hairdressing company.

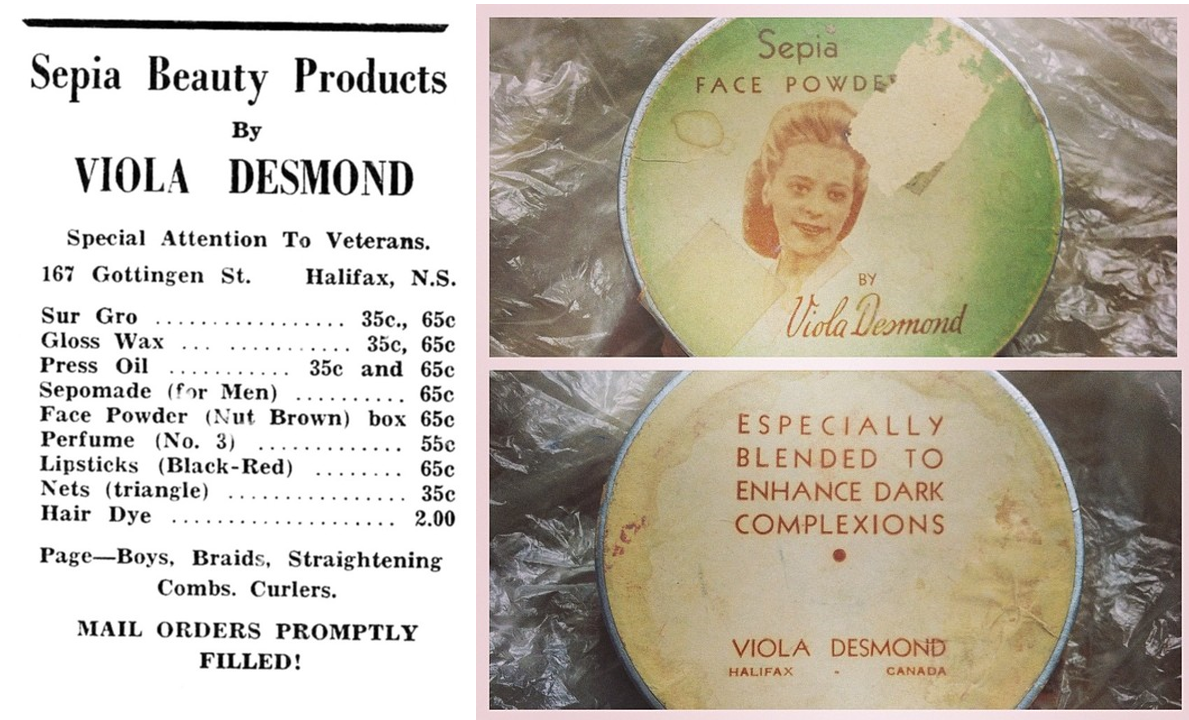

A newspaper advertisement for Sepia Beauty Products by Viola Desmond (left). A tin of sepia face powder sold by Viola Desmond (right).

Saving money from her teacher’s salary, she opened her own salon. Here, she offered training to young Black women interested in becoming beauticians. In addition to meeting their hair needs, clients were able to purchase Desmond’s own hair and beauty products. Desmond drew inspiration from Madam C.J. Walker, a self-made millionaire who manufactured and sold beauty products to African Americans.

Desmond often travelled for business. On November 8, 1946, she left Halifax but ran into car trouble (she owned her own car, which was unusual for a woman at that time). She stopped at a service station in New Glasgow and was told that her car would be fixed by the following day. She decided to catch a 7p.m. movie to pass the time.

Arriving at the Roseland Theatre, Desmond purchased her ticket from the cashier and proceeded to sit in the main seating area. The ticket-taker approached Desmond and told her that her ticket was for the balcony. In response, Desmond returned to the counter to pay the ten-cent difference in the ticket price. She was told by the cashier that “we are not allowed to sell tickets to you people.” The usher insisted that Desmond move to the balcony, but she remained in her seat.

The former Roseland Theatre in downtown New Glasgow as it appeared in 2017. (Image by Sean Marshall)

At that moment, Desmond made a conscious but spontaneous decision to take a stand against racial segregation.

In the face of her intransigence, the manager called the police, who forcibly ejected Desmond from the theatre and arrested her. Desmond spent 12 hours in jail and appeared in court the next day without legal representation. When Desmond took the stand, she explained to the Magistrate that she offered to pay the difference in price for the main seating area, but the cashier refused.

The court found Desmond guilty of a technicality—tax evasion—and she was ordered to pay $26.00. An appeal to overturn Desmond’s conviction was dismissed.

The front page of The Clarion detailed Viola Desmond's case.

Following her arrest, Desmond was supported by the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NSAACP), which provided funds to hire a lawyer. Civil Rights activist Carrie M. Best used her newspaper, the Clarion to publicize Desmond’s mistreatment. Desmond’s case also galvanized ordinary Black Nova Scotians in the struggle against racial inequality.

The significance and lessons of the case, particularly for Canadians, continue to reverberate today. As Desmond’s story illustrates, Canada must continue to grapple with its own historical and contemporary treatment of Black citizens.

Canadians often compare themselves positively to the United States, pointing to the latter’s history of slavery, Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), and race riots. But doing so obscures the fact that slavery and KKK chapters also existed across Canada. Comparisons to the United States serve only to obscure or sanitize the country’s own record of historical injustice.

Ku Klux Klan members stand by a cross erected in a field near Kingston, Ontario in 1927.

At the same time, Desmond’s actions also offer a powerful reminder that Black Canadians and their descendants collectively and individually resisted the oppression they faced.

That Desmond was chosen to be on the $10 bill following an open call for nominations and a public opinion survey on the Bank of Canada website is indicative of a willingness to acknowledge a small down payment on a longstanding debt. In 2021, racialized Canadians are still facing the long-term effects of racial inequality. This includes earning less, a lower quality of life, and continued injustice in all aspects of Canadian life.

Prior to Demond’s face appearing on the ten-dollar bill the province of Nova Scotia pardoned her in 2010 and offered a posthumous apology to her family. In 2012, her image appeared on a stamp and, in 2021, the government of Nova Scotia repaid the fine levied against Desmond.

Viola Desmond’s decision to sit in the main seating area of the Roseland Theatre struck a blow against anti-Black racism and made a case for respect and dignity. May her act of defiance not be in vain.