If prostitution is mankind's oldest profession, then grave robbing may be a close second. Since the ancient and classical era those with the resources created elaborate means to protect their remains from being disturbed. Until the eighteenth century those who disturbed graves were usually in search of the loot rumored alongside the dead. Yet in the first few decades of the nineteenth century the dead bodies themselves became precious commodities because the dissection of human cadavers for anatomical study had become an essential element of training in Europe's medical schools.

This sort of research was legally prohibited in England, though in 1752 anatomists won a small victory when they were given permission to dissect executed convicted murderers. As capitol punishment began to lose favor in England in the early nineteenth century, however, the supply in Edinburgh, perhaps the preeminent center of medical training and dissection in the western world at the time, had dwindled to 2-3 corpses a year, hardly enough cadavers to go around when direct knowledge of anatomy had become a prerequisite for obtaining employment after medical school.

"Resurrectionists" quickly filled the gap between the supply and demand. They gained the scorn of their countrymen as they disinterred newly buried corpses and sold them to anatomy schools for a tidy profit in what had become a thriving black market. The fear of having your loved ones dragged from their fresh grave was powerful enough that many burial sites at the time employed armed sentries to guard against such activity. By 1829 the situation in the churchyards was dire enough that a reform committee submitted an act to parliament that would provide a legal supply of cadavers and thus keep anatomists elbow deep in organs. Although reform of the system of some sort or another seemed rather certain at the time, the arrest of William Burke and William Hare, ensured that the English government would be much more involved in managing a legal supply of subjects for dissection.

Burke and Hare took the resurrection business one step further than others. They skipped the nasty, and sometimes dangerous, chore of unearthing corpses and instead went straight to an untapped and ever-replenishing source of bodies by killing unsuspecting victims which they quickly sold to the prominent Edinburgh anatomist Dr. Robert Knox.

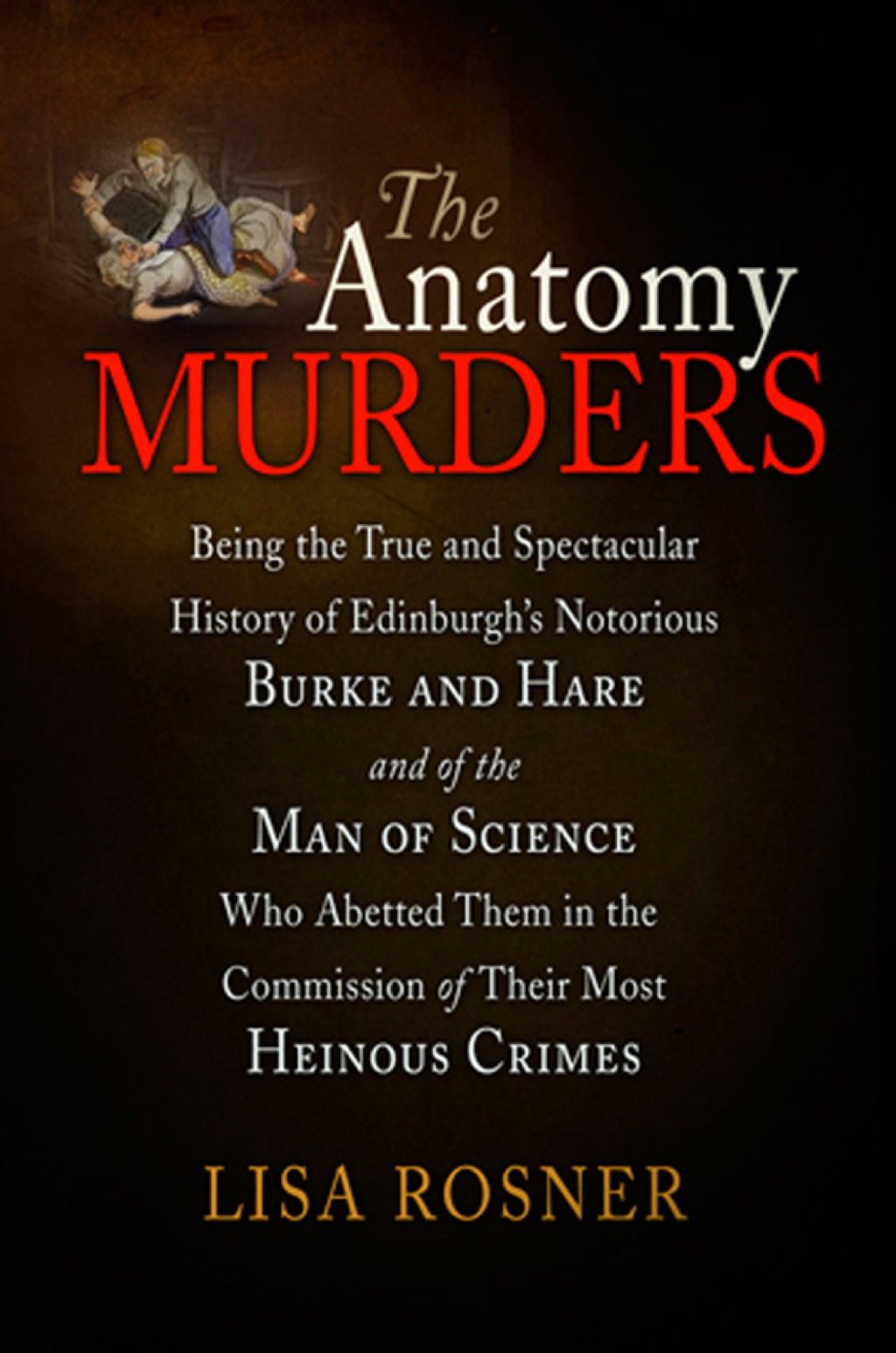

Lisa Rosner's The Anatomy Murders tells the story of Burke and Hare's murderous year in which their first victim was dispatched in January of 1828 and their last, rather appropriately, was killed on Halloween night of the same year. As Rosner tells it, fresh bodies were of particular value, and so Burke and Hare were offered a premium of £10 for their steady supply.

In their ten months of work Burke and Hare provided Dr. Knox with seventeen bodies for dissection (to be fair they only killed sixteen of them as the first transaction involved a women who had died of natural causes). The episode continues to live on as the Oxford English Dictionary defines "burke" as killing someone secretly by suffocation or for the purpose of selling the body for dissection. While Rosner provides little new information about this episode, she is at her best when she is analyzing the historical context which enabled so many victims to disappear without creating a stir from the authorities, and in illuminating how such a dastardly market for dead bodies came to be.

As Rosner tells it, while Edinburgh was not necessarily a hotbed of industrialization akin to Manchester and Liverpool at the time, its burgeoning industry was a siren song for the poor hoping to find gainful employment, and every fall thousands of Irish made the trip across the North Channel. Although on his arrest Burke announced his occupation as cobbler he and his mistress supplemented their income by taking in boarders. With so many itinerant laborers moving in and out of the city nobody seemed to notice when a handful seemed to disappear.

Rosner makes it clear that Burke and Hare were calculating and cold in dispatching their unwitting victims. But she also has real disdain for the anatomists, especially Dr. Knox, who so willingly paid for what they knew were bodies dragged from their graves. After receiving a new corpse to cut apart, Knox and his competing anatomists started with the face just in case the authorities came around asking questions. As long as the medical practitioners of Edinburgh continued to receive corpses to dissect, and as long as eager medical students continued to pay to watch such proceedings (for extra a student could dissect a body of their own) few questions were asked.

The story of Burke and Hare is fascinating in its own right and surely deserves to be read by a larger public and has only been waiting for the right person to tell the story. Rosner's The Anatomy Murders is that work. For his part Dr. Knox asked to be buried in a verdant churchyard. And although Knox was never charged with a crime, his connection to Burke and Hare derailed what could have been an influential medical career. For his part William Burke was convicted of murder, hung one month later, and had his own body dissected at the Edinburgh Medical College.