The history of fishing predates our own species.

Preserved wooden spears suggest that hominids began to hunt fish at least half a million years ago. This was not a haphazard operation, but rather a skilled practice.

A Neanderthal cave discovered above the Rhône River, for instance, contained tools covered in scales and bone fragments, shedding light on Paleolithic fish processing.

Some of the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens fishing comes from Central Africa where catfish were captured using barbed spears, a technology that remained sufficient for millennia. Humans using a rock shelter in East Timor around 40,000 years ago left signs of budding ocean fishing, discarding over 38,000 fish bones that revealed their preference for skipjack tuna.

Many of these fishing techniques used by early humans remained the same over hundreds of generations, yet the practice would eventually transform from an opportunistic subsistence activity to a specialized profession that lay at the heart of urban growth and worldwide trade and migration.

This is the remarkable story that Brian Fagan tells in his most recent work, Fishing: How the Sea Fed Civilization.

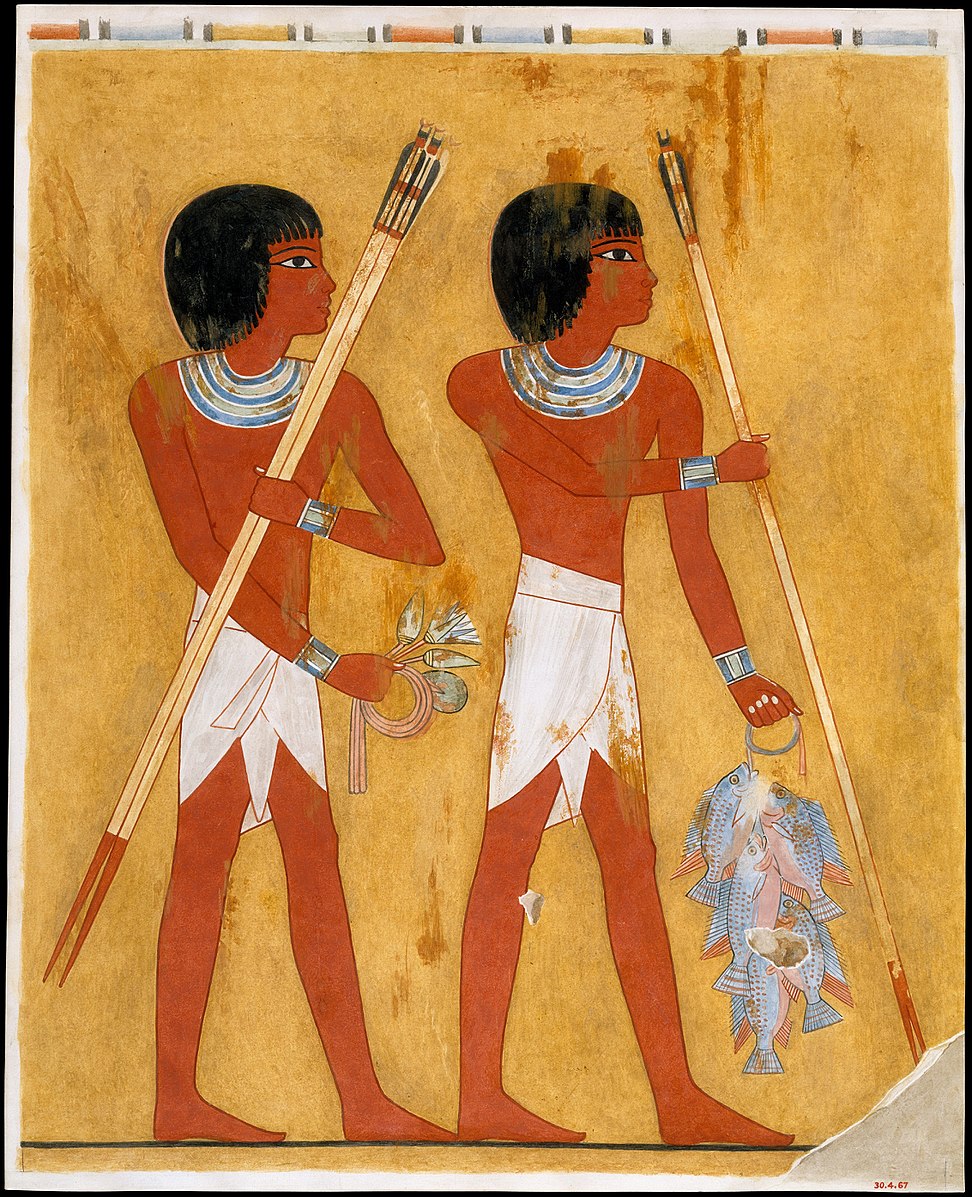

An Ancient Egyptian portrayal of fishing in the Tomb of Qenamun.

Fagan approaches the history of fishing, which he defines broadly to include oft-forgotten marine invertebrates, from a truly global perspective. The book’s twenty-three chapters move frequently between geographic regions and across time, beginning with the early Holocene (which began roughly twelve-thousand years ago) and ending with modern fishing practices.

Readers encounter diverse lifestyles from the Gidjingali Aborigines of Australia to the Jomon society of Japan to the Chumash people of America’s Channel Islands. While historical documents are scarce for many of his subjects, Fagan nonetheless has been able to synthesize research that uses a wide array of methods to reconstruct these early lives in extraordinary detail.

Technological advancements in archeology have enabled extensive chemical analyses of fish bones. These studies reveal not only what fish species people were consuming, but also the weight of a fish and even its geographical origins. Through this data, Fagan reconstructs the features of extinct cultures, deciphering their technology, seasonal movements, and hunting techniques.

Even when limited written records do exist, such as in the case of medieval Europe, evidence from isotope analysis of bones adds depth to our understanding that fish were traded internationally among northern countries.

Human bones also hold historical clues for Fagan. Remains from the Paloma settlement in Peru suggest an exceptionally high-protein diet, likely from anchovies and sardines, as well as a gendered and socially-stratified society where men possessed the greatest nutritional advantages.

A Tahitian fishhook made from mother of pearl and turtle shell, ca. 1768-1780.

These archeological details not only illuminate technological, cultural, economic, and social history, but they also engage the reader: we can clearly visualize Mediterranean fishers creating lines from goat hair or Hawaiians transforming human bones into fish-hooks.

Fishing is also a story of technological variety as humans around the globe solved the same basic problem in a multitude of ways. For example, Tahitians used toxic leaves to poison fish and constructed nets over seventy meters long while Aleutians used bull kelp and cedar bark to fabricate fishing lines that could withstand the force of halibut, a fish capable of reaching a quarter ton in weight. Their fish-hooks likewise drew strength from knots in conifer wood, often decorated with the image of an octopus or devil fish as spiritual aid for the fisher.

The breadth of Fagan’s work is one of its most notable features, but its organization leads to repetition and may leave some readers searching for the broader analytical takeaway. For instance, Fagan notes that “Central and southern China offer a great contrast to the experience of Jomon fishers.” However, this Japanese society was discussed eleven chapters earlier, reducing the impact of any comparison.

The lack of chronology or strong thematic organization also impairs one of the book’s strongest arguments. Fishers are described as the “anonymous background” that made possible elaborate civilizations such as those in Ancient Egypt, Rome, or the Andes. These societies relied upon dried and salted fish rations to energize massive labor and military forces and to develop specialized roles in society that did not involve food production. A well-supported argument, it nonetheless becomes fragmented in the narrative.

Nevertheless, Fagan’s assertion that fishing was foundational to societies worldwide is significant. In fact, this point can help us reimagine certain historical developments. Fishing provided stability not only for hunter-gatherers in times of scare game, but also for river valley agricultural societies like those in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, which relied on sometimes volatile water systems for irrigation.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Fagan’s story, though, is the role that fish played in global migration. The long voyages associated with Indian Ocean trade and European exploration and colonialism were only possible because of specialized communities that emerged to catch and process fish, which could be easily transported and safely stored for months. This movement then led to the discovery of new fisheries, such as Newfoundland cod, reinforcing the view of fish as a commodity.

Fagan ends his work by briefly examining modern industrial-scale fishing. The use of trawlers has decimated fisheries around the world. However, he is also careful to note that the blame cannot be placed solely on modern enterprises, as “the present condition of the world’s fishing grounds is the culmination of thousands of years of exploitation of the oceans, exacerbated by the assumption that fish were a limitless resource.”

The hope remains that stricter regulations and the creation of habitat reserves will help these aquatic populations, which have given us civilization, rebound. As Fagan notes, “such an approach requires a highly unfashionable degree of long-term thinking.” This book is a step in that direction.