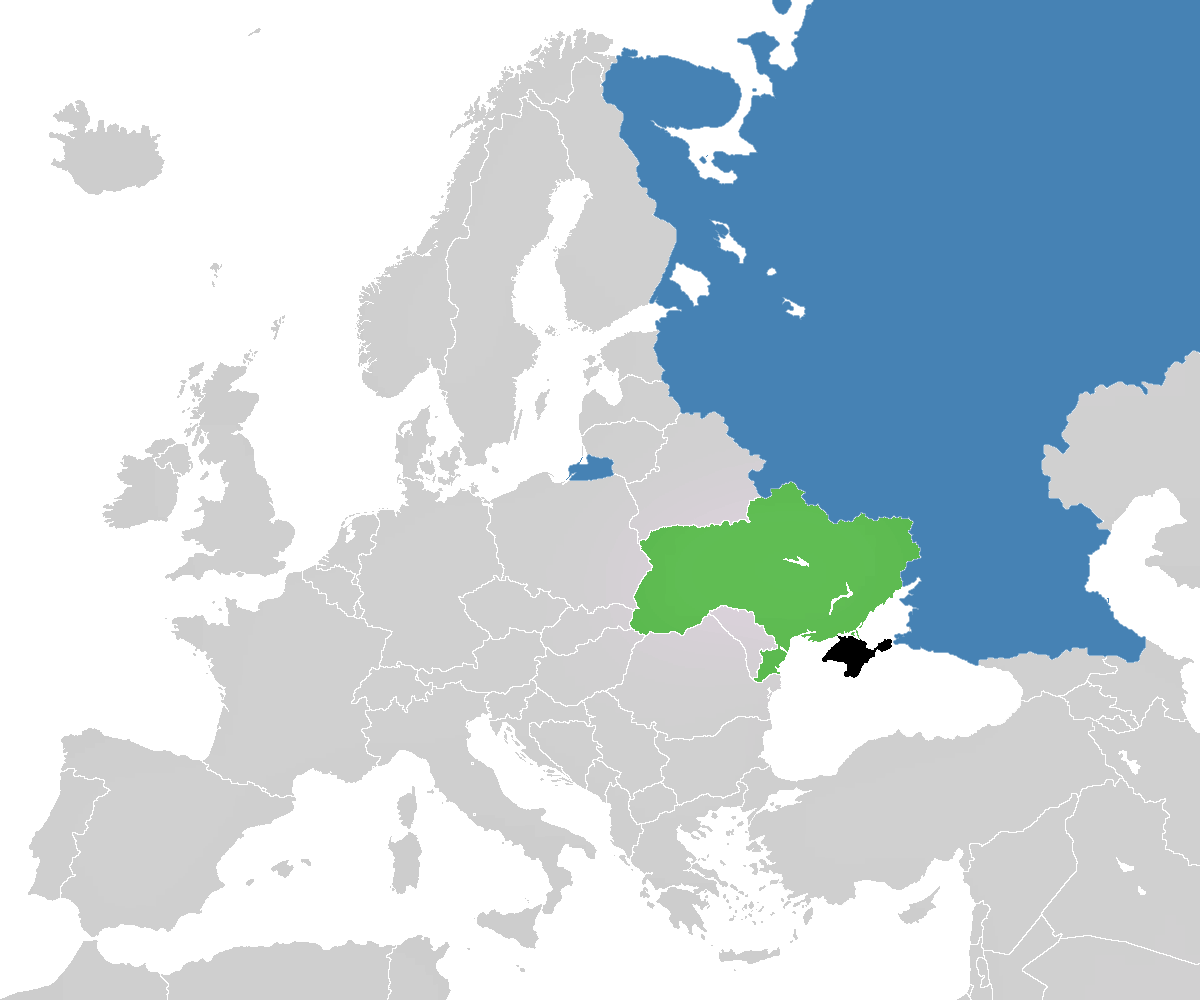

Until 2014, Ukraine was a country little known and poorly-understood by many in the West. While the Ukrainian Revolution of February 2014 and the subsequent annexation of the Crimean peninsula by Russia have certainly given the country more name recognition, understanding is still hard to find. Neil Kent attempts to fix that and introduce Crimea to a wider audience with his new book Crimea: A History.

Kent, who is much better known for his work on Arctic and Scandinavian history, takes a broad view of history for this book. Considering its relative shortness, this means moving quickly through a rapid succession of ancient peoples who have inhabited the Crimean peninsula , including the Scythians, the Greeks, the Romans, and the Goths, among others. This comprises the first chapter of Kent’s history. The next three chapters take the reader through the Middle Ages, the Crimean Khanate, and the Ottoman Empire, leading into Crimea’s integration, along with Ukraine (then called Novorossiya, or “New Russia”) into the Russian Empire.

The remaining six chapters deal with the history of Crimea almost exclusively through the lens of its relationship with Russia. These chapters are devoted to its consolidation into the Empire, its experience of the Crimean War and both World Wars, the immediate post-war period, and the transference of the peninsula from Russia to Ukraine by Khrushchev and its role in the late- to post-Soviet world. The book finishes with an epilogue about Crimea in the twenty-first century, primarily focused on the protests and revolution of 2014 and Crimea’s annexation by Russia. The chapters are brief, and split further into small sections organized for the benefit of readers who are unfamiliar with the subject.

Kent’s basic argument is that Crimea is, at its core, a part of Europe, with much more in common with the West than the East. He writes that “its peoples and culture were European, not Asiatic, even if over a millennium ago many of those who had settled [there] had come from far to the east” (1). Other than its statement early on, however, the argumentation is fairly subtle; he rarely comes out and restates it, but it is implied in how he deals overwhelmingly with Crimean interactions with Russia, and, to a lesser extent, with Western Europe. After the fourth chapter, the focus is almost entirely off the East.

In some ways, Kent’s book is a very welcome addition to the scholarship surrounding Crimea. Nearly every book that has been written about it is set within the context of a war. Very few general histories have been written about the peninsula itself. Some might argue that this leads the book into an almost old-fashioned political history. This should not necessarily be considered a weakness, however. The book is clearly intended for a more general audience, and if Kent’s intention was to encourage interest from the public in Crimean history, this kind of history was likely the most effective way to get it.

There raises some more serious concerns, however. The first chapter, despite speeding through thirteen centuries of Crimean history, contains not a single citation. The second chapter contains three, and the following chapters range anywhere from seven cited sources to seventy. Even when citations are prevalent, they might make the academic reader a bit uneasy. In the third chapter, fifteen out of thirty-two citations come from Maria Ivanics’ book on the Crimean Khanate. In chapter six, thirty-four out of sixty-nine come from Orlando Figes’ book on the Crimean War, and in chapter eight Paul Robert Magocsi’s book on the Tatars accounts for nine of the fifteen. This may not seem like a serious problem, considering that the book is marketed to a general audience, but it forces any reader to raise an eyebrow and wonder if Kent relies too heavily on a single sources.

There are also a few concerns about factual inaccuracies. For example, Kent refers to the “last official census before the current political upheavals,” which occurred in 2001. He claims that in that census, 63 percent of citizens claimed to identify as Russians (7), when, in actuality, the number is closer to 58 percent.[1] Later, in the epilogue, when Kent discusses the actions of the Russian Unity party, a pro-Russian political party based in Crimea, he mistakenly refers to it as the United Russian Party (154, 155), which, technically, does not exist; it seems as though he’s mixed it up with United Russia, the political party in Russia with which Vladimir Putin is affiliated. It is absolutely critical to a meaningful study of Crimea that these be distinguished properly.

The biggest concern regarding Kent’s book, however, lies in his argument. He says that Crimea is, at its heart, European, but he justifies that claim of Europeanness primarily by way of its association with Russia. The trouble with this is that perhaps the biggest, most fundamental and long-standing question in Russian history is whether or not it can be considered European. Is Russia European, or not? Is it Asiatic? Is it both? Something else entirely? Historians have gone back and forth on this issue for centuries now, and so to hang Crimea’s Europeanness on a country whose own Europeanness is hardly certain seems dubious at best, and perhaps academically irresponsible.

Overall, if Kent’s primary goal for Crimea: A History is to provide a general audience with a way into understanding this pivotal peninsula, then he is successful. The prose flows well and is quite readable, and the text is broken up into very manageable pieces that guide and direct the reader, while allowing for digestion and comprehension. Ultimately, and especially considering the dearth of comparable titles, this book would serve as a perfectly suitable introduction to Crimean history for the uninitiated, even if it does not quite hold up to academic standards.

[1] State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality/Crimea/ (retrieved May 23, 2016).