African history before the colonial era has been relegated to the periphery of most studies of this period. In African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa, however, Michael A. Gomez places West African empires—particularly those of Ghana, Mali, and the Songhay—within a global, medieval context, especially their relations to the Islamic world.

The book has fourteen chapters, which are split into four parts. Part 1 focusses on the early history of West Africa and the Sahel region. Gomez considers the proto-empires of the region, which include the growth of the city of Gao and the Kingdom of Ghana. In this section, Gomez also introduces his readers to how the institution of West African slavery related to Islamic states such as Egypt and Syria, which were the major purchasers of West African slaves.

In conjunction with this discussion of slavery, Gomez tackles the idea of race during this period. He notes that “blackness” was not the defining aspect of a slave in Islamic culture at the time, but rather his or her proximity to a centre of “civilization.” This interesting discussion warrants its own, book-length study.

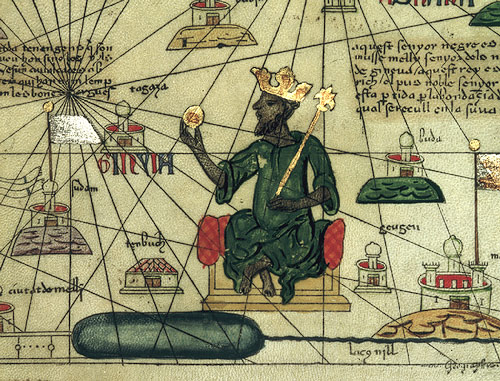

Part 2 of African Dominion explores the origins and span of the Empire of Mali. Mali grew out of the Ghanaian Kingdom, and Gomez charts the emergence, development and demise of this empire. Gomez goes on to illustrate how interconnected each empire was and how intricate and complex politics were in West Africa during this period. He examines Mansa Musa’s famous pilgrimage to Mecca, and goes on to describe West Africa’s emergence onto the global stage. The final chapter of Part 2 analyses the intrigue of the Imperial Malian court.

The Songhay Empire forms the bulk of Parts 3 and 4. Part 3 traces the development of Imperial Songhay from its origins in the declining Mali Empire. Gender is a more prominent issue in this and the next section of the book, owing to the power of queens and concubines in the Songhay court.

The gender dynamics explored by Gomez make this book a valuable contribution to the historiography of Africa, and Western audiences will appreciate this in-depth discussion of a too-often ignored topic. The power of women in the Imperial courts is often surprising, and further research will make for an interesting book in itself.

Part 4 analyses the eventual demise of the Songhay Empire because of a Moroccan invasion from across the Sahara Desert. Included in this section is a chapter devoted to the last great emperor of the Songhay, Askia Dawud. This is another of many examples of Gomez’s gift for bringing historical actors to life; these reanimations allow the reader to understand life in contemporary West Africa by truly appreciating the individuality of the story’s central characters. This is something not often seen in pre-colonial African histories.

Gomez portrays the shift of power in West Africa in tandem with global developments, as well as how these empires affected other centres of power such as European and the Islamic civilizations. In other words, African empires were affected by global trade and politics just as much as Europe or Asia, and these influences shaped the West African empires.

Gomez makes use of a variety of sources for this work. Most importantly is his use of the oral tradition in conjunction with Arabic documentary evidence. The Arabic documentary evidence are traditional primary sources: many were written in these West African empires. The existence of these records illustrates Islam’s reach into West African society. An example of this is Ibn Battuta’s travel journals. It is important to note that the majority of Gomez’s Arabic documentary sources reside today in their original place of creation: Timbuktu.

But the use of oral histories balances the narrative by including voices that have generally not been heard in histories of this region. In fact, the oral tradition is gaining importance as a source for historical research, and this book amply shows how useful and important oral histories can be.

One possible obstacle that might trip up non-specialist readers is the dual dating system employed by Gomez. In his citations the Islamic date is noted before the Gregorian, so that the seventh century becomes the “seventh/thirteenth,” and the tenth the “tenth/sixteenth century.” This can cause confusion for the reader, but one can understand the logic, as West African empires were, after all, Islamic for the majority of their history: they would have followed the Islamic calendar.

Excepting this minor critique, African Dominion is an excellent, readable book on a region often forgotten by medieval historians. Apart from his most obvious and important contributions to gender and global history in the African context, Gomez blazes a path for future pre-colonial historians.

Interested parties will learn much from Gomez about how to go about their research. It is sure to become a seminal work in this field, and I would suggest anyone who is interested in pre-colonial African history to read it.