In a landmark vote, Scotland will take to the polls on September 18 to determine whether it remains a part of the United Kingdom or separates to become an independent state. As the prospect of an independent Scotland looms, these ten historical moments help us understand the long and complicated relationship among Scotland, England, and the United Kingdom.

1. The United Kingdom: A State of Nations

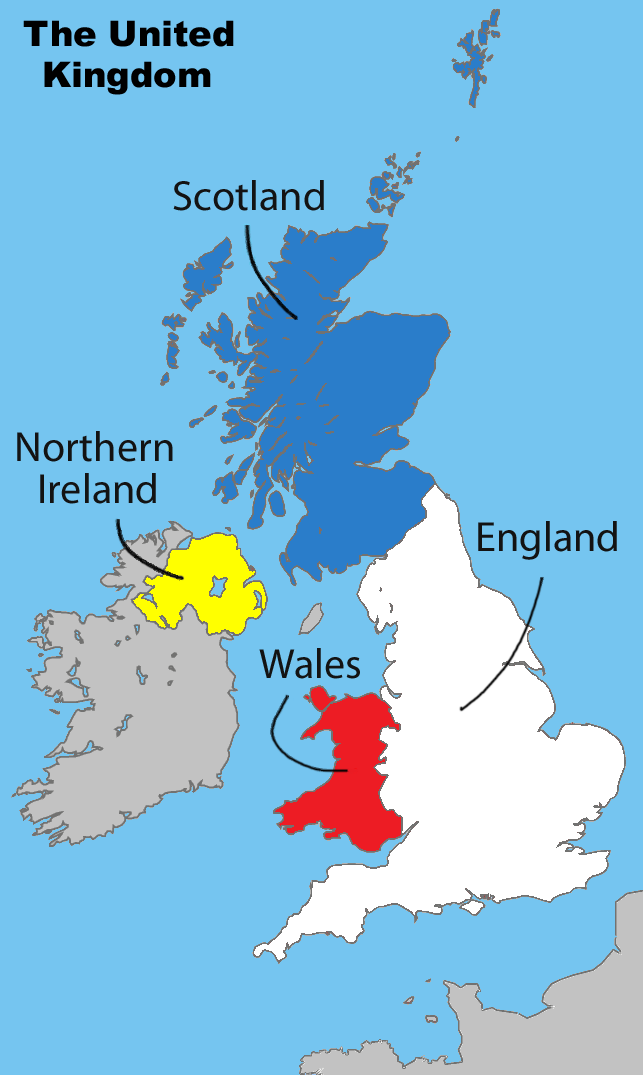

Understanding Scotland’s position in the United Kingdom requires first understanding the UK’s idiosyncratic political structure. The United Kingdom—or, in its full version, The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland—is a collection of individual nations united under a single political state: England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Until recently, the UK Parliament, which meets at Westminster in London, was the only legislature for all four nations. While Westminster remains the UK’s supreme legislative body, devolutionary movements in Scotland (see #9), Wales, and Northern Ireland have established local governments that deal with domestic matters like education, health, agriculture, and justice.

2. Robert the Bruce and the Scottish War for Independence

Long before Scotland was a member of the UK, it was a sovereign state with its own government and monarchy. In 1296, Edward I of England invaded Scotland, defeating King John Balliol’s forces at the Battle of Dunbar. The defeat and its aftermath placed the kingdom in English hands. Discontent among the Scottish population led to a series of revolts, however, with the most famous organized by Andrew de Moray and William Wallace (now of Braveheart fame). But it was Robert the Bruce that led Scottish forces to a decisive victory in 1314 against Edward I’s son, Edward II, at the Battle of Bannockburn. Six years later, the Declaration of Arbroath affirmed Scottish independence, and in 1328, Robert and the English king Edward III signed the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, which once again recognized Scottish independence and Robert’s monarchy.

3. The Union of the Crowns: Two Crowns, One Head

In 1603, Elizabeth I of England and Ireland died. Her successor, James Stuart VI, King of Scotland, became James I of England and Ireland, uniting the three realms under a single monarch.

Scotland maintained its sovereignty and its parliament, with only policies like overseas diplomacy controlled uniformly by the unified monarch. James VI and I was essentially a monarch with two crowns. And the Scottish Stuart family then ruled the three realms (with an interregnum from 1649 to 1660) until George I of the Hanoverian dynasty succeeded to the throne in 1714.

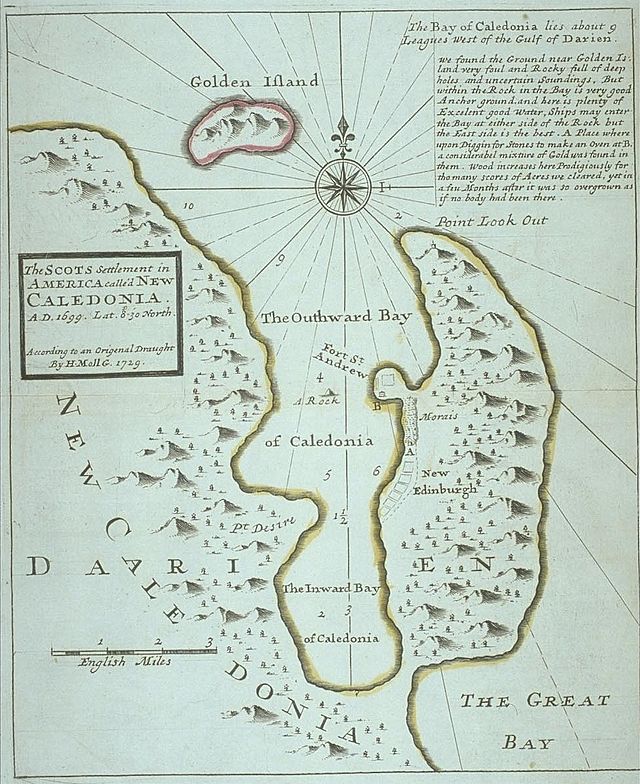

4. The Darien Scheme: A Colonial Disaster

Scotland’s one colonial attempt proved disastrous. Proposed as economic and political protection against significant English pressure, the colony was located on the Isthmus of Panama, near the Gulf of Darién. The first expedition set sail in 1698 and established the settlement of New Edinburgh. Poor agriculture, illness, Spanish blockades, English interference, and the unwillingness of local natives to trade made the settlement an almost instantaneous catastrophe. The project was backed by significant Scottish wealth, and its failure effectively ruined the country. Financial costs and political fallout weakened the will of Scottish nobles and landowners, paving the way for union with England and the creation of the United Kingdom.

5. The Acts of Union: Parliaments United

Beginning in the 16th century, English economic power made it much stronger than Scotland, which experienced a series of crippling political and economic disasters. England attempted to solidify that dominance by incorporating Scotland into a unified state. Landowners in Scotland, still suffering from the Darien Scheme, saw union as a chance to recoup their wealth in England’s significantly more vibrant economy. Since Scotland and England were separate nations, both the Scottish and English Parliaments individually had to pass acts to ratify the Treaty of Union.

Scottish popular opinion was decidedly opposed to the union. Riots erupted in the streets throughout Scottish towns when a draft of the treaty was made public. Yet, despite popular opposition (and with the help of bribery and blackmail), the acts passed both parliamentary houses. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was established.

6. Jacobite Rising of 1745 and Culloden

In 1745, Charles Edward Stuart, great-great-grandson of James VI and I, attempted to reestablish the Stuart monarchy in England and Scotland. Supporters of “Bonnie Prince Charlie’s” ascension, commonly known as Jacobites (from the Latin for James), came largely from Scotland’s Highland clans.

Despite an initial victory near Edinburgh and a march into England, the rebellion was underfunded and poorly supported. Its failure reached a violent climax at the Battle of Culloden, where British soldiers decimated Jacobite forces. The brutal crackdown and the civil penalties set in place after the battle weakened Highland culture and undermined the clan system.

By the 19th century, however, the Jacobite Rising became the stuff of tragic legend, and much of the romanticism that now surrounds the Highlands—clan culture, bagpipes, tartanry, etc.—can be traced to its events. Sir Walter Scott’s series of Waverley novels, set in Scotland during the rebellion, became incredibly popular in 19th-century Britain and were said to be particular favorites of Queen Victoria, who had established her summer retreat in the Highlands at Balmoral Castle.

7. Red Clydeside: Radical Labor in Scottish Industry

In 19th- and early-20th-century Scotland, industry and manufacturing became the nation’s central economic engines, particularly in the Central Belt between Glasgow and Edinburgh. With industrialization came an increased presence of organized labor, particularly in Clydeside, the region around Glasgow along the banks of the River Clyde. Political radicalism reached a peak between the 1910s and the 1930s, and the region became known as Red Clydeside.

On January 31, 1919, trade unions rallied on Glasgow’s George Square, calling for a 40-hour work week and improved labor conditions. Tens of thousands attended, and police presence provoked fighting and, eventually, rioting. UK Prime Minister David Lloyd George, fearing a Bolshevik revolution similar to the one in Russia only two years earlier, called for military intervention, and ten thousand armed troops, with tanks and howitzers, occupied Glasgow.

8. The Failed 1979 Devolution Referendum and the 40% Rule

The desire for greater Scottish autonomy brewed in the 1970s. The Scotland Act of 1978 organized a referendum in 1979 to establish a devolved Scottish Assembly, which would have powers of local governance separate from Westminster. One provision, known as the “40% Rule,” required approval by 40% of Scotland’s total registered electorate. While the referendum passed a simple majority, with 52% of participants approving, nearly 37% of the voting population did not participate. This lack of participation meant that only 33% of the total registered electorate approved the referendum, thus failing the 40% Rule and preventing the formation of a Scottish Assembly.

9. 1997 Devolution Referendum: Scottish Parliament Reconvenes

Another referendum vote was held in 1997 to establish devolved powers for a Scottish Parliament. Voters were asked two questions: 1) Should a Scottish Parliament be established and 2) Should that parliament have tax-varying powers. Both provisions, which did not have to overcome a 40% Rule, passed with overwhelming majorities. After the successful referendum, the UK Parliament passed the Scotland Act 1998, which reconstituted the Scottish Parliament. Following elections held in March 1999, the Scottish Parliament reconvened on July 1 for the first time since 1707.

10. SNP and the Independence Referendum

In 2007, the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) formed a minority government in the Scottish Parliament, and they followed that success with a majority victory in the 2011 election. With a majority government in place, the SNP, led by Alex Salmond, called for a referendum on Scottish independence.

While the Scottish government currently controls domestic matters, independence would allow for more power to control foreign policy, trade and energy issues, and welfare policy, among others.

Still, many questions remain and the debate has intensified as the vote approaches. How would an independent Scotland determine citizenship? What currency would it use? What would happen with the oil revenue from the North Sea? Would Scotland automatically join the European Union? Would it be a member of NATO? Where would the UK store its trident nuclear missiles, currently at the Clyde Naval Base on Scotland’s west coast? And, finally, would the people of Scotland be better off on their own?