The poster for HBO’s Chernobyl.

“What is the cost of lies?”

This question, posed by scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris) opens HBO’s Chernobyl and is the central focus of this television event. The series (created/written by Craig Mazin, directed by Johan Renck) follows the efforts of Legasov, Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skärsgard), and Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson) to respond to the Chernobyl disaster. The tragedy began when Reactor #4 at the V.I. Lenin Atomic Energy Station exploded during a safety test in Soviet Ukraine in the early hours of April 26, 1986.

The lies begin immediately. In the aftermath of the explosion, the overseer of the control room of Reactor #4, Anatoly Dyatlov (Paul Ritter), refuses to acknowledge the reality of what has happened. The plant’s leadership follows suit, lying as much to themselves as to everyone else.

The historical record supports the series’ unsparing portrayal of the plant’s leadership. Dyatlov, especially, acted with recklessness, continuing the test even when it was clear that serious issues had developed. The fifth episode, portraying the decisions that led to the explosion in vivid and accurate detail, is a notable dramatic achievement.

Chernobyl reveals, though, that the lies began before the explosion, and were part of a much deeper rot in the Soviet system. Reactor #4 was a RBMK reactor, a Soviet model that prioritized power output and ease of construction over safety.

The design suffered from several flaws, most critically with its emergency shutdown system. In theory, when operators pressed the AZ-5 button, the control rods that would stop the nuclear reaction would be inserted immediately to avoid potential catastrophe. In certain circumstances, however, inserting the rods could produce a brief but critical moment in which the nuclear reaction increased. At Chernobyl, pressing the emergency shutdown button was, perversely, the immediate cause of the explosion.

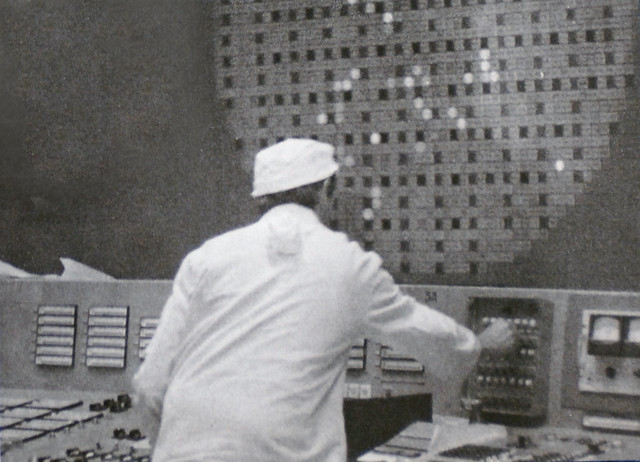

A plant employee at work, mid-1980s.

In any complex system, accidents are inevitable, but the Soviet obsession with secrecy exacerbated the potential for an accident. Soviet authorities knew of the AZ-5 flaw, but they classified this information, just like previous nuclear accidents. Admitting flaws meant admitting that the image of technological ascendancy the Soviet Union wanted to project was a lie. Commitment to this image by Soviet authorities meant that the lie of the RBMK’s safety became an unquestioned official truth.

The series depicts the cost of these lies in graphic detail, drawing stories from the oral history Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich (2015 Nobel laureate in Literature). The third episode shows the gruesome effects of Acute Radiation Syndrome, suffered by plant workers and firefighters. Much of the fourth episode depicts the experience of the liquidators sent to prevent further contamination. Most extraordinarily, the series portrays the true-to-life use of “bio-robots” (i.e. people) to clear the plant’s roof of highly radioactive debris when mechanical means had failed.

The series does take significant dramatic licenses with its three main characters, all of whom take on the actions of dozens of other responders to the crisis. Emily Watson’s Khomyuk, most notably, is a composite character meant to represent several of the scientists who worked at Chernobyl. Legasov, meanwhile, is portrayed as unrealistically naïve about the realities of Soviet bureaucracy. In the final episode when the plant’s leadership is on trial, Legasov exposes the Soviet government’s culpability. This scene is a pure invention.

The grave of Valery Legasov. In 1996, he was named a Hero of the Russian Federation for his courage in investigating the cause of the explosion.

Fortunately, such dramatization does not prevent the show from achieving an accuracy of spirit. While there was no dramatic trial moment, Legasov advocated for reform and faced professional and personal consequences as a result. And while he did commit suicide shortly after the second anniversary of the explosion, he did not kill himself at the exact minute of the explosion. Writer Mazin is open in interviews and in the podcast accompanying the show about what was and was not dramatic license.

Such candor has often not been the case in narratives around Chernobyl.

The disaster has spawned different and often competing stories, especially between the Soviet and then Russian governments, on the one hand, and those impacted by the disaster, on the other. The number of casualties is a matter of scientific and political dispute, and is woven into the post-Soviet clashes between Russian and Ukrainian historical memory. The series ends with an epilogue noting that, while the official death toll remains 31, other estimates have ranged from 4,000 to 93,000, with some estimates climbing even higher.

Reactor #4 the day after the explosion.

Chernobyl is ultimately a deeply frightening story about the danger of refusing to accept reality in favor of political ideology. The Soviet Union provided many examples of this danger, but such refusal is not only a Soviet phenomenon. Chernobyl is a reminder that lies have a cost and, eventually, reality will catch up with you.