This month marks the first anniversary of the Parkland shooting, when a gunman killed 17 students and staff members at a high school in Florida. In the aftermath, states around the country passed 50 new laws regulating guns. Meanwhile, gun-rights advocates, who argue that the government lacks the constitutional right to regulate gun production and ownership, have prevented Congress from enacting federal legislation.

The history of gun control predates the nation itself. American colonies and then states regulated guns in the 18th and 19th centuries and the federal government regulated the gun industry. In the current debate between “gun rights” and “gun regulation,” both sides rely on history to make their case. So here is a review of ten crucial moments in the history of gun regulation in the United States.

Student activists participate in a “lie-in” in front of the White House in the aftermath of the Majory Stoneman Douglas High School Shooting in February 2018.

1. English Tradition

Propaganda by Paul Revere depicting the Boston Massacre of 1770, during which the British Army killed several people.

Americans inherited the notion of an individual’s right to bear arms from English legal tradition—an ancient right codified in the English Bill of Rights (1689). Americans justified rebellion in the 1770s by invoking their rights as English subjects to counter perceived injustices by the British military.

Yet, they also inherited the English common law tradition of regulating arms. English statutes dating to the 14th century limited gun use and the Bill of Rights specified that arms were for defense “as allowed by law.” Colonial leaders carefully policed gun use. James Madison, before framing the Constitution and Bill of Rights, proposed legislation that prohibited firearm use outside of hunting season. Rights and regulation went hand-in-hand in colonial America.

2. The Constitution

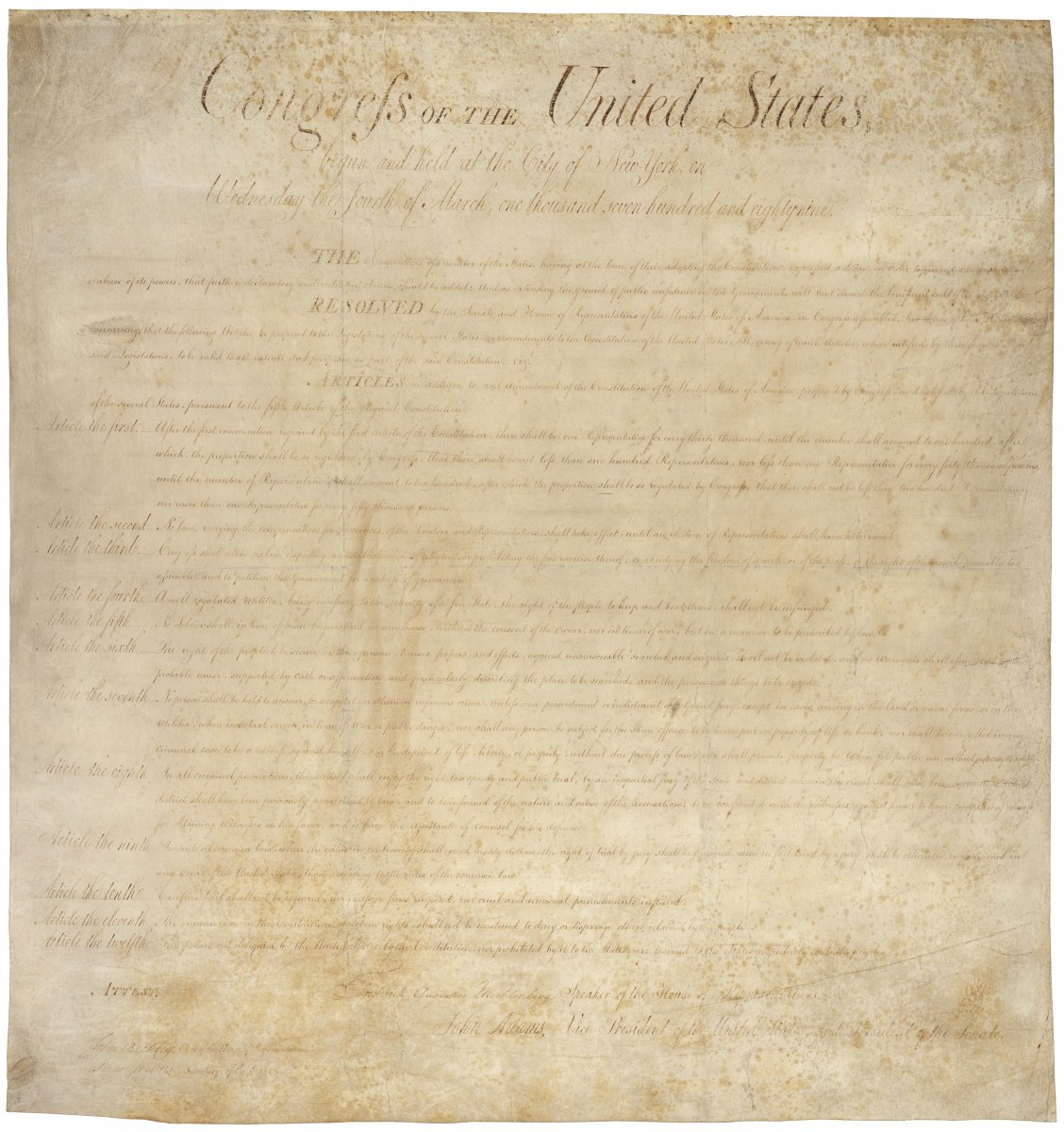

The original twelve articles of the Bill of Rights, in which the Second Amendment is listed as “article the fourth.”

The Constitution refers to arms twice. Article 1, Section 8 gives Congress the power to arm the militia and the Second Amendment mandates that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Congressional debates over the wording of the Second Amendment centered on the relationship between state and federal control of citizens’ security and linked bearing arms to civic duty. Despite its common invocation today by gun rights advocates as the guarantor of an individual’s right to possess firearms, the Amendment was rarely mentioned before the early 20th century.

3. The 1790s

In 1794, troops armed by the 1792 Militia Act partook in suppressing Pennsylvania’s Whiskey Rebellion.

Early federal policymakers did not consider it their duty to protect citizens’ rights to carry arms. Instead, they worried about supplying and regulating them. The Militia Act of 1792 required militia members to supply their own muskets, but many struggled to arm themselves in the face of post-war shortages. Congress prohibited the export of arms and made their import mostly duty-free during the early 1790s. In 1792, Congress gave the president power to select two sites for the nation’s federal armories. George Washington chose Springfield, MA and Harpers Ferry, VA. Three years later, Springfield manufactured the nation’s first public musket, known as the Model 1795. Modeled after a French weapon, it became the standard U.S. musket until the War of 1812 and marked the origins of federal standardization.

4. Government Arms Contractors and Private Industry

A U.S. Musket Model 1816 Type III; the federal government at the time provided weapon standards for private contractors.

Congress passed legislation in 1808 to appropriate $200,000 annually to provide arms and military equipment to state militias. It stipulated that these funds go to private manufacturers because many congressmen and their constituents opposed centralizing arms production at federal armories. This law set the precedent for federal intervention in private gun factories. For the next three decades, the War Department issued five-year renewable contracts with a slate of requirements. All gun parts had to conform to federal standards and pass regular inspections. Contractors had little choice but to conform because they depended on federal patronage

5. Regulating Safety in the 1830s

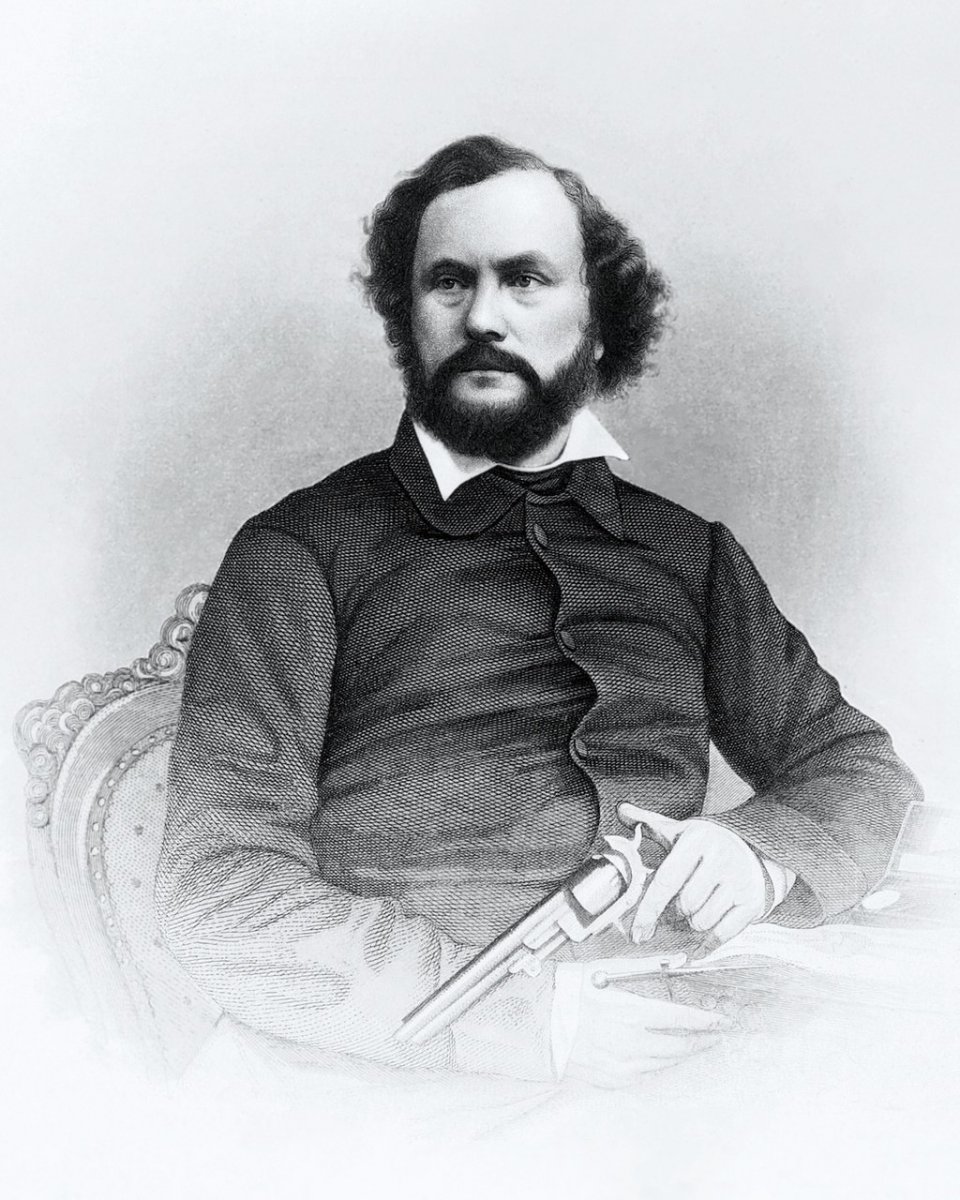

The Ordnance Department tested firearms made by private arms manufacturers, such as Samuel Colt.

The federal government not only subsidized and standardized the manufacture of firearms, it also regulated their safety. In the 1830s, as Congress reevaluated the balance between private and public production for the military, lawmakers asked military officers to compare the safety and effectiveness of firearms manufactured by federal armories and private contractors. During the first round of tests (in 1837), officers preferred the standard U.S. musket and decided there was “risk to the national safety by adopting new inventions without being convinced of their superiority.”

The government would not purchase weapons from new contractors without testing them first. Samuel Colt, for example, solicited government patronage in the 1830s, but had to adapt to federal safety standards when a board of ordnance officers expressed concern that several features of new revolvers caused risks, including hearing loss. After selling government-tested firearms, Colt went on to become one of the nation’s most iconic private arms manufacturers.

6. State Laws

In many states—including New Hampshire, pictured here—residents are allowed the right of open carry of firearms.

Many early state laws prohibited carrying a firearm in public. Gradually, states began to permit carrying if one had “reasonable fear of assault,” but fined weapon owners who disturbed the peace. Throughout the nineteenth century, states considered it perfectly legitimate to limit firearm use. In the 1870s, for example, the Texas Supreme Court upheld a law requiring any person carrying a weapon to have “good cause.” In 1923, the U.S. Revolver Association published a model law that required a person to demonstrate reasonable fear before they could get a permit to carry a weapon in public. Several states adopted this legislation, including California, Connecticut, and Indiana. Other states, like Oklahoma, banned carrying guns outright. By 1987, only one state permitted unrestricted concealed carry. That number now stands at 14.

7. Jim Crow, the Second Amendment, and the Supreme Court

In the two hundred-plus years after the ratification of the Second Amendment, the Supreme Court infrequently addressed the constitutional relationship between gun rights and gun control.

The rights—or the lack thereof—of African Americans first brought the Second Amendment to the Supreme Court. In Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) the Court indirectly linked citizenship with firearms rights by arguing that if the law made black men citizens, it would have to grant them the right to bear arms. The Second Amendment received more explicit treatment in U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876), which ruled that states could prohibit African Americans from keeping arms because the Second Amendment only applied to the federal government. The Court privileged racial discrimination over Second Amendment protections by arguing that states could limit gun possession.

8. Early Federal Legislation

The National Firearms Acts of 1934 and 1938 required registration for machine guns and other weapons associated with criminal activities.

Although the federal government had long regulated aspects of the firearm industry, it enacted specific gun control legislation for the first time after World War I. A rise in organized crime in the late 1920s and 1930s inspired more interventionist legislation. After unsuccessful efforts to ban the interstate shipment of firearms through the U.S. postal system, Congress passed the National Firearms Acts of 1934 and 1938. These laws required registration and high taxes for machine guns and other weapons associated with criminal activities, prohibited gun sales to convicted criminals, and mandated the licensing of interstate gun dealers. The acts represented the first regulation of certain types of firearm sales and ownership at the federal level. Organized crime decreased, despite lax enforcement, and the laws received little attention for two decades.

9. The Rise of the Gun Lobby

The National Rifle Association was founded in 1871 to promote improved marksmanship and firearms safety. In the twentieth century, it became a powerful gun-rights lobbying group whose opposition to all forms of gun control has made it the frequent target of outrage.

In the second half of the twentieth century, an increase in gun violence prompted Congress to expand the Federal Firearms Act with the Gun Control Act of 1968. This congressional action lead to the rise of the gun lobby. The National Rifle Association, founded in 1871 to improve marksmanship and gun safety, pivoted to lobbying to counter this legislation. In 1976, it launched a political action committee, the Political Victory Fund, to support expansive gun rights.

Lobbyists have battled it out ever since. The National Council to Control Handguns (NCCH), founded in 1974, and later renamed the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, helped pass the Brady Act of 1993, which strengthened federal gun control by requiring background checks for gun buyers. Anti-gun control activists, on the other hand, achieved a victory in 2005 with legislation that limited federal inspections of gun dealers and granted gun manufacturers immunity from civil lawsuits over crimes committed with firearms.

10. District of Columbia v. Heller

Ultimately, the issue of gun control remains contentious, with both pro- and anti-gun control activists turning to history to justify their approach.

On June 6, 2008, the Supreme Court ruled that provisions in the District of Columbia's Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 violated the Second Amendment. It defined for the first time an individual’s right to own a firearm unconnected with militia use, so long as the firearm is in “common use.” Two years later, the Court expanded the implications of the Heller decision, which applied to a federal enclave, to state and local governments in McDonald v. Chicago.

The Court, however, also made clear that the Amendment should not be understood as an unlimited right and certain types of weapons ought to be regulated. This leaves legislative space for the slate of new gun control laws currently being passed, especially as Heller recognized that sound decisions were consistent with “the historical understanding of the scope of the right.” Both opponents and proponents of stronger gun control have interpreted the Heller decision as reinforcing their views. The case ultimately affirmed that for gun regulation, historical precedent matters.