The Civil War in Syria has become one of the most bloody and geopolitically important events to come out of the Arab Spring. While the war has become in many ways a sectarian Shi’a-Sunni battle, in Syria there is a third religious group that has played a pivotal role in the history of that country: the Alawites. This month historian Ayse Baltacioglu-Brammer outlines the history of this little known community and describes how they became perhaps the most important power bloc in Syria after the 1970s. She reminds us that we cannot understand the civil war raging in Syria without understanding the Alawites.

Read more on Syria and the Middle East: Syria's Islamic Movement; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; U.S.-Iranian Relations; U.S.-Iraq Relations; Turkish Politics; and The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Podcast Update: be sure to catch Ayse, along with Patrick Scharfe, on our podcast of History Talk covering the Syrian Civil War as they discuss the various groups involved, women's rights, the perils of intervention, and the path ahead.

When in early March 2011 the “Arab Spring”—a wave of pro-democracy demonstrations that began in Tunisia in late 2010 and swept across Libya and Egypt—finally reached Syria, people from various religious and ethnic backgrounds (Muslims, non-Muslims, and Alawites; Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmen) rallied together to oppose the regime of Bashar al-Assad, the “elected” president of Syria.

The unrest resulted from a combination of socio-economic and political problems that had been building for years and that affect especially Syria’s large rural population. The drought of 2007-2010, high unemployment rates, inflation, income inequality, and declining oil resources all contributed to profound discontent on the part of the opposition movement. Moreover, harsh and arbitrary political repression had also eroded Bashar al-Assad’s long-cultivated facade as a “reformer.”

In the early days of the rebellion, the frequent protest chant, "Syrians are one!" indicated the determination of the demonstrators to show the unity of the opposition movement, which, according to them, was above any sectarian and ethnic division and dispute. In an unusual show of solidarity, in Latakia, the fifth largest city in Syria and one with a major Alawite population, a Sunni Imam led prayers for Alawites, while the Alawite Shaykh led prayers at a Sunni Mosque.

However, two years after the conflict began in the midst of tremendous hope and optimism, it has degenerated into a civil war with more than 100,000 deaths and 2 million refugees. And it has put Syria at the center of nasty geopolitical struggles involving the United States, Russia, Iran, Lebanon, and Turkey.

The war today has in many ways become a war fought between the majority Sunnis, on one side, and Shi'ites with the support of minority Alawites on the other.

Alawites are adherents of a syncretistic belief with close affinity to Shi'ite Islam and, importantly, the Assad family is Alawite. But despite their crucial role in the unfolding struggles in Syria, they are little known outside the region.

In most discussions of the Syrian civil war, the most neglected question is: How and why did an opposition movement that initially included various religious and ethnic segments of the Syrian society against a dictatorial regime turn into another sectarian war between Sunnis and Shi'ites?

Answering this question requires us to appreciate the peculiar position occupied by Syrian Alawites and the role played by them in the creation of the modern state of Syria.

We also need to understand how sectarian differences have long been used as a political tool by the Assad family—who have ruled Syria since Bashar al-Assad's father Hafez al-Assad took power in the 1970s—and, before them, by the French who controlled Syria for much of the 20th century.

Who are the Alawites?

Today Alawites comprise 12-15% of the Syria’s population, or about 2 million people. They mainly live in the mountainous areas of Latakia on the northwestern coast, where they constitute almost two-thirds of the population.

The Alawites are composed of several main tribes with numerous sub-tribes. Syria’s Alawites are also divided among two distinct groups: more conservative members of the community, who mainly live in rural regions as peasant farmers and value the traditional aspects and rituals of the belief, and the middle-class, educated, urban Alawites who have been assimilated into Twelver Shi'ism aided by Iranian and Lebanese propaganda. [Twelver Shi'ism is the principal and largest branch of Shi’ite Islam.]

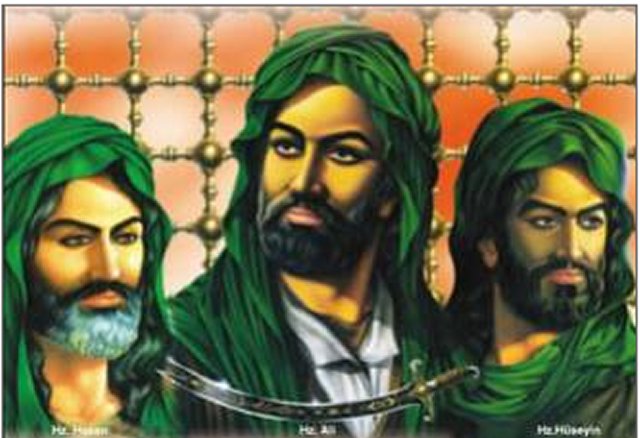

Syria’s Alawites are a part of the broader Alawite population who live between northern Lebanon and southern-central Turkey. While not doctrinally Shi'ite, Alawites hold Ali (d. 661), who is considered the first Imam by the Shi'ites (and the fourth caliph by the Sunnis), in special reverence.

The sect is believed to have been founded by Ibn Nusayr (d. ca. 868), who was allegedly a disciple of the tenth and eleventh Shi'ite Imams and declared himself the bab (gateway to truth), a key figure in Shi'ite theology. Alawites were called “Nusayris” until the French, when they seized control of Syria in 1920, imposed the name “Alawite,” meaning the followers of Ali, in order to accentuate the sect's similarities to Shi'ite Islam.

The origins of the Alawite sect, however, still remain obscure.

While some scholars claim that it began as a Shi'ite faction, others argue that early Alawites were pagans who adopted themes and motifs first from Christianity and then from Islam. In essence, Alawism is an antinomian religion with limited religious obligations. Despite similarities to the Shi'ite branch of Islam, some argue that Ibn Nusayr's doctrines made Alawism almost a separate religion.

The Alawites believe in the absolute unity and transcendence of God, who is indefinable and unknowable. God, however, reveals himself periodically to humankind in a Trinitarian form. This, according to the Alawite theology, has happened seven times in history, the last and final being in Ali, Muhammad, and Salman al-Farisi, who was a Persian disciple and close companion of Muhammad.

The Alawites hold Ali to be the (Jesus-like) incarnation of divinity. While mainstream Muslims (both Sunni and Shi'ite) proclaim their faith with the phrase “There is no deity but God and Muhammad is His prophet,” Alawites assert, “There is no deity but Ali, no veil but Muhammad, and no bab but Salman.”

Alawites, furthermore, ignore Islamic sanitary practices, dietary restrictions, and religious rituals. The syncretistic nature of the Alawite belief is further evident in its calendar, which is replete with festivals of Christian, Persian, and Muslim origin.

Giving Ali primacy over the Muhammad, a feature shared by various ghulāt (Shi’ite extremist) sects, permitting wine drinking, not requiring women to be veiled, holding ceremonies at night, and several pagan practices have led mainstream Muslims to label Alawites to be often singled out as heretics or extremists.

In Syria, ethnically and linguistically Arab, the Alawites developed certain characteristics that isolated them from the Sunni Syrian population.

Alawites before the 20th Century

Uncertainty about Alawites’ religious identity confused observers and produced suspicion among political and religious authorities that often resulted in persecution over the centuries.

The first proponents of the Alawite faith fled to Syria from Iraq in the 10th century. In the 11th century they were forced out of the Levantine cities and into the inhospitable coastal mountains of northwestern Syria, which has remained the heartland of the Alawites ever since.

In the 14th century, Alawite marginalization was perpetuated by the first anti-Alawite fatwa (legal decision) by a Sunni scholar, Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328), which essentially proclaimed Alawite belief as heresy. Thereafter Alawites suffered major repression by the Mamluks (r. 1250-1517) who ruled the region. Geographically isolated, Alawites maintained their religious integrity in the face of continuous attacks and invasions.

In the Ottoman era (1517-1918), ill treatment continued as Alawites were considered neither Muslim nor dhimmi (a religious group with certain autonomy with regard to communal practices such as Christians and Jews) by the Ottoman government in Istanbul. On the other hand, during much of Ottoman rule, Alawites could practice their religion and a few enjoyed official positions.

The main reason for tension between central Ottoman authority and the Alawite community stemmed from Ottoman efforts to impose its authority by collecting revenue from their local regions. Alawites, who acquired a reputation as “fierce and unruly mountain people,” frequently resisted paying taxes and plundered the Sunni villages.

Attempts by later Ottoman governments to enroll Alawites in the army served as another reason for the Alawite uprisings and perpetuated the strong resentment towards Sunnis, who had so often been seen as their oppressors.

At the end of the 19th century, Alawites rose up against the Ottoman government demanding more autonomy. The rule of Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876-1908) did little to diminish these desires, even though he allowed some Alawites to make careers in the Ottoman army and bureaucracy.

The Alawites enjoyed little benefit from the centralized Ottoman government and its largely Sunni-based policies that attempted to convert locals to Sunni Islam through building of mosques in Alawite villages and Sunni training of Alawite children.

The “Turkification” policies pursued by the Young Turks—a group of secularist and nationalist activists who organized a revolution against the Ottoman monarchy in 1908 and ruled the empire until 1918—accelerated the cooperation of the Alawites with new actors in the region: the French.

Alawites during the French Mandate and the Alawite State of 1922

The Alawite region became a part of Syria as a byproduct of the notoriously secret 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain. It was placed under the French mandate after the end of World War I.

After defeating and evicting the British-backed Syrian King Faysal in 1920, France, in a divide-and-rule strategy, partitioned Syrian territories into four parts, one of which was Latakia, where most of the population was Alawite.

By promoting separate identities and creating autonomous zones in Syria along the lines of ethnic and sectarian differences, the French mandate aimed to maximize French control and influence in Syria. Muslim and Christian minorities were the main allies of the French against the Arab nationalism rooted among the urban Sunni elite.

Furthermore, Alawite territory was geographically crucial because French forces could use it to control the whole Levant coast.

During the mandate era, many local leaders supported the creation of a separate Alawite nation. Alawite cooperation with French authorities culminated on July 1, 1922 when Alawite territory became an independent state. The new state had low taxation and a sizeable French subsidy.

This independence did not last long. Although Latakia lost its autonomous status in December 1936, the province continued to benefit from a “special administrative and financial regime.”

In return, Alawites helped maintain French rule in the region. For instance, they provided a disproportionate number of soldiers to the French mandate government, forming about half of the troupes spéciales du Levant.

Alawitepeasants, who were not only religiously repressed and socially isolated by mainstream Sunni Muslims but also economically exploited by their fellow Alawite landowners, rushed to enlist their sons for the mandate army. As a result, a large number of Alawites from mountain and rural areas became officers and they formed the backbone of the political apparatus that would emerge in the 1960s.

French policy ultimately served its purpose to increase the sense of separateness between the political center and the autonomous states in Syria's outlying areas.

In Paris in 1936, when France entered into negotiations with Syrian nationalists about Syrian independence, some Alawites sent memoranda written by community leaders emphasizing “the profoundness of the abyss” between Alawites and Sunni Syrians. Alawite leaders, such as Sulayman Ali al-Assad, the grandfather of Hafez al-Assad, rejected any type of attachment to an independent Syria and wished to stay autonomous under French protection.

Yet the Alawite community remained divided over the future of the community. Despite a deep sense of religious difference, an increasing number of Alawites and Sunni Arabs were coming to believe that the inclusion of Alawites in a unified Syria was inevitable. People both within and without Syria worked toward a rapprochement between the predominant Muslims and minority Alawites.

For instance, Muhammad Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who was the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places from 1921 to 1938 and known as a leading Arab nationalist, issued a fatwa declaring Syrian Alawites to be known as Muslim. With this fatwa, al-Husseini aimed to unite the Syrian people against the Western occupation.

Following in his footsteps, several Alawite sheikhs made further statements emphasizing their adherence to the Muslim community (albeit Shi'ite) and to Arab nationalism. Also, a group of Alawite students were sent to the Najaf province of Iraq to be trained on the Shi'ite doctrines of Islam.

For all the benefits of French rule for the Alawites, the French Mandate ultimately did little to improve the economic conditions of the Alawite population as a whole. Newly-emerged ideologist parties such as the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) utilized this fact to turn Alawites against the French and toward Arab nationalism.

Alawites after World War II

It was during the Second World War that the future of the Syrian state and its constituent parts were shaped. When war broke out in 1939, a new generation of Alawites proved more flexible in cooperating with Syrian nationalists, most of whom were Sunni urban elites.

With the formation of Vichy France in mid-1940, ultimate power and authority in Syria rested with the British, who favored the creation of a unified independent Syria under the leadership of urban Sunni elite. Even though the Alawite territories belonged to independent Syria, historical mistrust between the Alawites and Sunnis made the transformation a lengthy and painful process.

After the war, Syria obtained independence in 1946, but entered into a period of political instability, unrest, and experimentation with pan-Arab connections to Egypt.

Once they recognized that their future lay within independent Syria, Alawites started to play an active role in two key institutions: the armed forces and political parties.

The Ba'ath party, founded in 1947 by several Muslim and Christian Arab politicians and intellectuals to integrate the ideologies of Arab nationalism, socialism, secularism, and anti-imperialism, was more attractive to Alawites than the Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni conservative religious organization headquartered in Egypt with a large urban Sunni base in Syria.

Alawites and other minorities continued to be over-represented in the army due to two main factors. Middle-class Sunni families tended to despise the army as a profession, which, according to them, was the place for “the lazy, the rebellious, and the academically backward.” Alawites, on the other hand, saw the military as the main opportunity for a better life.

Second, many Alawites, who had been coping with dire economic circumstances, could not afford to pay the fee to exempt their children from military service.

The Alawite presence in the military culminated in a set of coups in the 1960s. The final coup was carried out by General Hafez al-Assad, himself an Alawite, and brought the Alawite minority to power in Syria in November 1970. In February 1971, Hafez al-Assad became the first Alawite President of Syria.

Alawites and the Assad Dynasty

Born to a relatively well-off Alawite family in a remote village located in northwestern Syria, Hafez al-Assad joined the Ba'ath Party in 1946 and rose to the rank of de facto commander of the Syrian army by 1969. Sectarian solidarity has been a crucial component of Assad family rule from the beginning. He relied on the Alawite community to consolidate his power and to establish his dynasty.

In the early stages of his rule, Hafez al-Assad emphasized Syria's pan-Arab orientation that required him to embrace the majority Sunni population. In 1971, he reinstated the old presidential Islamic oath, lifted restrictions on Muslim institutions, and encouraged the construction of new mosques.

At the same time, however, Assad not only placed trusted Alawites in key positions of the regime's security apparatus, but he also improved their living conditions, long among the most degraded in the Arab world. While rural Alawites benefitted from infrastructure improvements such as electricity, water, new roads, and agricultural subsidies, a group of urban Alawites enjoyed employment opportunities in the army and the state bureaucracy.

Overall, Alawites felt a sense of pride that "one of their own" had raised himself to such a high position.

In the end, Assad was unable to win the allegiance of large sections of Sunni Muslim urban society, particularly the conservatives with connections to the Muslim Brotherhood. His failure to fully bridge the divide was not only related to the heterodox character of his faith and certain anti-Islamic policies he adopted, but also to policies that favored his co-sectarians over the rest of the Syrian population.

The clashes between the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and the president, who symbolized the Alawite minority, culminated in rebellions against the regime in late 1970s and early 1980s.

Simultaneously, language used by the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters only served to magnify Alawite insecurity, lead Alawites to back the Assad regime, and exacerbate ongoing tension. For them, Alawites were kuffars (disbelievers).

The peak of this struggle was the battle in Hama in early February 1982, where Alawite (but also some Kurdish) troops killed around 30,000 Sunni civilians, effectively tying the fate of the Alawites to the Assad regime.

From that moment, politics in Syria have been dominated by sectarian divisions.

Sectarian insecurity among the Alawites—who believed that the fall of the regime could lead to revenge against their community following the events in Hama—led to a firm support for hereditary succession in Syrian government. An Alawite attendant at Hafiz al-Assad's funeral in 2000, therefore, did not hesitate to utter, “for us the most important [thing] is that the president should come from the Assad family.”

The Rule of Bashar al-Assad

Even though Bashar al-Assad’s inaugural slogan, “change through continuity,” was reassuring for Alawites, the same slogan was interpreted by the Sunni Syrian majority as an invitation to push for political change.

Bashar al-Assad's initial policies conveyed a message of economic and political reform, but his main strategy was redistributing the spoils of power among the loyal supporters of the regime and his family. These actions, rightfully called the "corporatization of corruption" by former Syrian vice president Abd al-Halim Khaddam, worked against not only the Sunni majority, but also many Alawites, who were left out of the small inner core that includes Bashar al-Assad, his brother, sister, brother-in-law, and cousins.

While the regime and its clients enjoyed unchecked power and wealth at the expense of the majority of Syrians, several instances of sectarian violence between Alawites and Sunnis erupted in Syria. The most recent of these outbreaks occurred in the summer of 2008. Bashar al-Assad used this violence as evidence to argue to Alawites that his authoritarian regime was the only protection for them from what he called Sunni fundamentalism and intolerance.

Moderate Alawites have challenged Assad’s fear-based justifications for his rule and many more liberal Alawites later joined the early protests against the Assad regime. They were much more concerned with Assad’s political oppression, corruption, nepotism, and economic troubles than with sectarian bonds.

The prospect of shattering the historical alliance between the Assad regime and Syria’s Alawites was a tantalizing opportunity for Sunni oppositional leaders.

With this goal in mind, former Syrian Muslim Brotherhood leader Ali Bayanouni reached out to the Alawites in 2006, stating: “The Alawites in Syria are part of the Syrian people and comprise many national factions … [The] present regime has tried to hide behind this community and mobilize it against Syrian society. But I believe that many Alawite elements oppose the regime, and there are Alawites who are being repressed. Therefore, I believe that all national forces and all components of the Syrian society, including the sons of the Alawite community, must participate in any future change operation in Syria.”

This statement differed dramatically from the antagonistic tone of previous Muslim Brotherhood statements about the heretical nature of the Alawite sect.

Bashar al-Assad, as a keen politician and skilled strategist, would not allow any type of rapprochement between his co-sectarians and the Sunni majority, which has been against the Assad regime for decades.

Beginning early in his reign, Bashar al-Assad not only began actively to emphasize his Alawite roots but also manipulated to his benefit an increasing trend among the Alawites of Syria: conversion to mainstream Shi'ite Islam. He followed policies of forging ties both with Alawites and Shi'ites in Syria as a conscious effort to transform the nature of the opposition, from a united front against his anti-democratic rule to sectarian conflict between the Sunnis and Shi'ites.

From Arab Spring to Civil War

The events of the Arab Spring destabilized Bashar al-Assad’s complicated efforts to balance and contain the forces opposed to his regime and emboldened these diverse challengers to stand together against him.

After protests began in Syria in January 2011, he quickly came to realize that the opposition movement was too powerful to control by turning yet again to the entrenched dependency between the Assad family and the Alawite minority.

As the regime used ever-increasing violence as its only recourse to suppress the opposition, Bashar al-Assad began to develop a new state policy to attract foreign support (especially from Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon) to secure his regime not just as another authoritarian government whose popularity was in decline, but rather as a Shi'ite state entrenched in the region against neighboring Sunni states, such as Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Turkey.

Al-Assad began to position himself as a pious Shi'ite through public events, appearances, and organizations. And the main Shi’ite political and military organizations in the region, Hezbollah and Iran, decided to back up the Assad regime in very concrete ways. They sent much needed financial and military support and ideologically bolstered Bashar al-Assad's fight against the Sunni “terrorists.”

The past eighteen months have proved that Bashar al-Assad’s strategy is serving its purpose as the nature of the conflict has transitioned into sectarian violence between Iran- and Hezbollah-backed Shi'ites and Sunnis, some of whom are backed by al-Qaida.

As has occurred repeatedly in its history, religious affiliations matter more than any other allegiance in the Syrian political arena and, after an initial burst of opposition to the Assad government, Syria’s Alawites have remained generally supportive (if wary) of his regime.

Despite a general feeling emerging in many Alawite villages that the Assad regime no longer represents them—particularly after affiliating itself with orthodox Shi'ite actors of the region, who have been known for their hostility against heterodox branches of Shi'ite Islam, including the Alawites—there is still a great deal of political power to gain for Bashar al-Assad from exploiting the deep-seated Alawite insecurity against the Sunni majority.

The Assad regime has already proved its willingness to drag Alawites, the Syrian state, and even the region, down with it into a violent sectarian chaos if it continues to be challenged.

Nevertheless, there remains an opportunity—perhaps now only a hope—for Alawites and Sunnis to break free from this political deadlock and form a supra-sectarian opposition that triggered the movement two years ago.

Douwes, Dick, The Ottomans in Syria: A History of Justice and Oppression, London, 1997.

Faksh, Mahmud A. “The Alawi Community of Syria: A New Dominant Political Force.” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Apr., 1984), pp. 133-153.

Fildis, Ayse Tekdal. “Roots of Alawite-Sunni Rivalry in Syria.”Middle East Policy, Vol. XIX, No. 2, Summer 2012.

Filiu, Jean-Pierre, The Arab Revolution: Ten Lessons from the Democratic Uprising, New York, 2011.

Gelvin, James L., Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1998.

_______., The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know, New York, 2012.

Hathaway, Jane (with contributions by Karl K. Barbir). The Arab Lands under Ottoman Rule, 1516-1800. Harlow: Pearson, 2008.

Heydemann, Steven, Authoritarianism in Syria: Institutions and Social Conflict, 1946-1970, Ithaca, 1999.

Khoury, Philip S., Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920-1945, Princeton, 1987.

Lust-Okar, Ellen, Structuring Conflict in the Arab World: Incumbents, Opponents, and Institutions, New York, 2005.

Lesch, David, The New Lion of Damascus: Bashar al-Asad and Modern Syria, New Haven, 2005.

Middle East Watch, Syria Unmasked: The Suppression of Human Rights by the Asad Regime, New Haven, 1991.

Owen, Roger, State, Power and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East, New York, 1992.

Perthes, Volker, The Political Economy of Syria under Asad, London, 1995.

Pipes, Daniel. “The Alawi Capture of Power in Syria.” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Oct., 1989), pp. 429-450.

Provence, Michael, The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism, Austin, 2005.

Roberts, David, The Baath and the Creation of Syria, New York, 1987.

Seale, Patrick, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989.

Sindawi, Khalid. “The Shiite Turn in Syria.” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, Vol. 8, pp. 82-107.

van Dam, Nikolaos, The Struggle for Power in Syria: Politics and Society under Asad and the Ba’th Party, New York, 1996.

Wedeen, Lisa, Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria, Chicago, 1999.