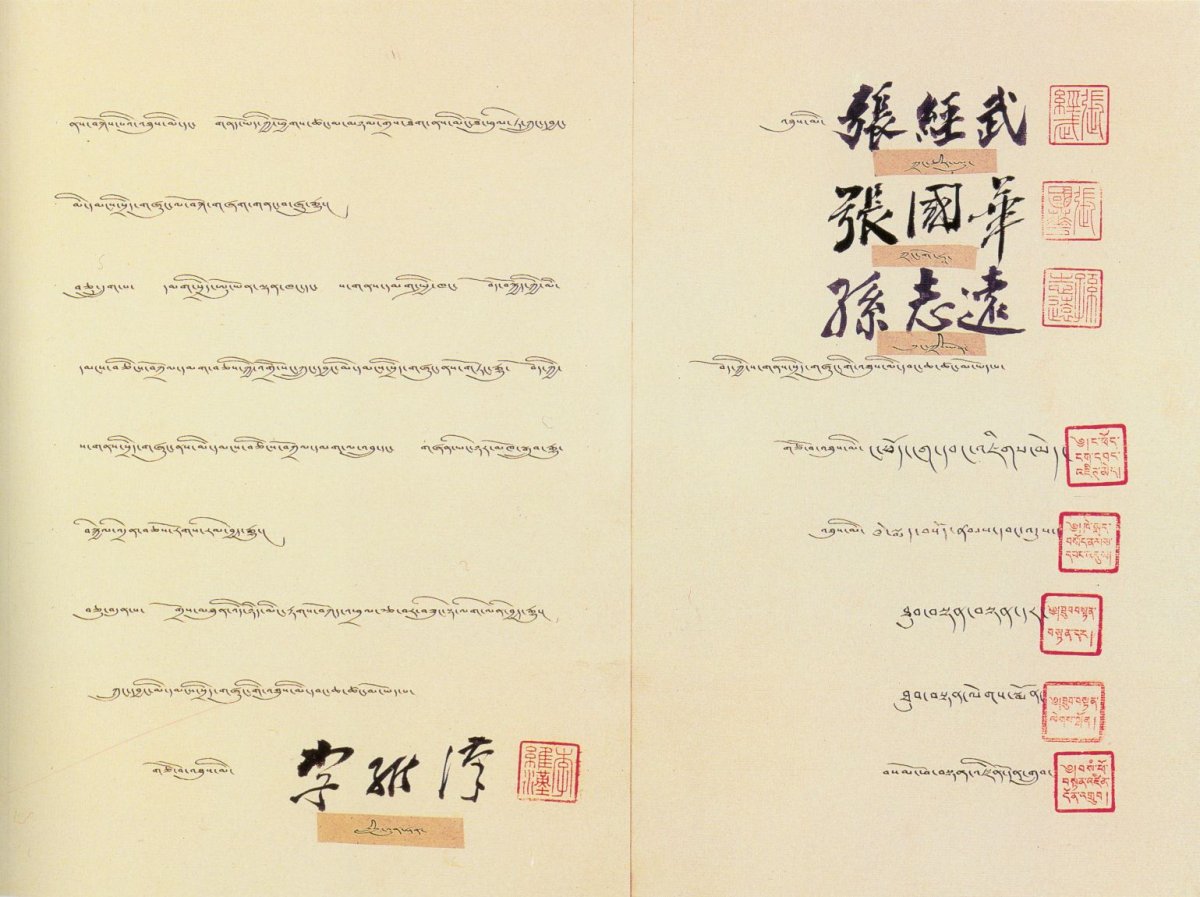

On May 23rd 1951, the "Seventeen Point Agreement of the Central People’s Government and the Local Government of Tibet on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet" was signed. This agreement legitimized claims of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) over Tibet and retroactively justified the previous year’s military invasion of eastern Tibet by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Delegates pose for a photo after signing the Seventeen Point Agreement in Beijing, 1951.

The document is the only agreement signed between the PRC and a minority people and is part of communist China’s larger nation-building process in its so-called “peripheries.” The existence of a fully functional independent state in Tibet made signing of the Seventeen Point Agreement a legal necessity for China.

The three traditional provinces that historically constitute Tibet had ruled their own affairs since the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912. Central Tibet (Ü-Tsang) was administered by the Ganden Phodrang government and headed by the Dalai Lama in the city of Lhasa. It was based on Tibetan Buddhism and the principles of “cho-si sungdrel,” or religion and politics combined.

The other two Tibetan provinces, Kham in the east and Amdo in the northeast, had their own local rulers, who nonetheless were faithful to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism. Several Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas (the second highest Buddhist hierarch), including the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Tenth Panchen Lama, hailed from Amdo.

The Seventeen Point Agreement was signed under duress. Beforehand, the PLA had occupied Amdo and Kham, and the Dalai Lama and his supporters had sought refuge in Dromo, south Tibet. According to the Dalai Lama’s autobiography, the negotiator Ngabo Ngawang Jigme was not authorized to sign anything on his behalf and counterfeit seals of the Tibetan state were used.

The terms of the agreement claimed that Tibet sought Chinese protection from imperialist powers. Clause One of the agreement stated that “The Tibetan people shall unite and drive out imperialist aggressive forces from Tibet; the Tibetan people shall return to the family of the Motherland – the PRC.”

As the Dalai Lama remarks in his autobiography, however, the only foreign army to have ever been stationed on Tibetan soil was the Manchu army in 1912. At the time of the Seventeen Point Agreement, there were only a handful of Europeans in Tibet.

Rather than liberating Tibetans, then, the agreement was a tool to consolidate China’s hold of Tibet. Though the agreement gestured toward Tibetan autonomy, six clauses from the Seventeen Point Agreement pertained to efforts to ensure Chinese national security on its frontiers.

Tibet has long been a strategic issue for China. Chinese policymakers from the late Qing period onwards saw Tibet as the backdoor for invaders to attack the Middle Kingdom. The communists under Mao Zedong acted on that same assumption.

A map of Tibet that shows its regions and position within Asia.

Yet, the Chinese absorption of Tibet created the conditions for border disputes between China and India. Both countries have engaged in armed conflict over the borders, most recently in May 2020 when the PLA and the Indian army clashed in the Galwan valley.

The agreement did provide a range of rights to Tibetans pertaining to religion, culture, and traditional institutions. The Tibetan political system was left intact, and with it the authority of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. In central Tibet, socialist reforms such as land redistribution were left to Tibetan authorities’ discretion, but the same was not the case in the eastern Tibet provinces of Kham and Ando, which were subjected to Chinese land redistribution policies beginning in the mid-1950s.

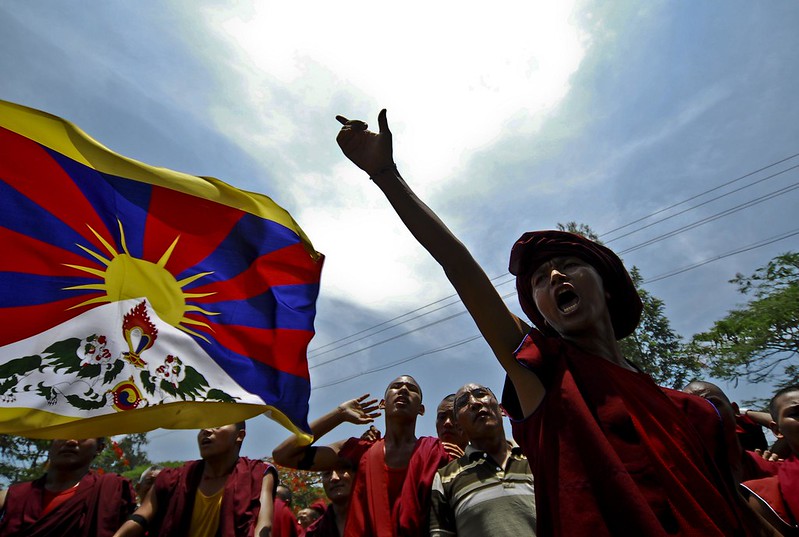

The imposition of these reforms, as well as the Chinese state’s refusal to respect the longstanding ties between the provinces of eastern and central Tibet, led to an armed uprising in Kham and Amdo beginning in 1956.

Recently declassified materials from Russian archives show that Communist forces used Soviet aircraft to bomb local monasteries in punitive missions. Tibetan guerrillas and civilian refugees fled into Lhasa, where they formed a resistance army known as the Chushi Gangdruk (whose name references the ancient name of eastern Tibet).

By 1959, the uprising spread to central Tibet. The CIA provided covert support for the Chushi Gangdruk and protesters in Lhasa declared Tibetan independence. Rumors spread that the Chinese were preparing to arrest the Dalai Lama, who escaped to India before the PLA retook Lhasa after heavy shelling.

The uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight marked the failure of the Seventeen Point Agreement. From exile, the Dalai Lama has continued to repudiate the agreement, claiming it was thrust upon the Tibetan government and people by the threat of arms.

The Dalai Lama arrives in Siliguri, India after fleeing Tibet, 1959.

The agreement was born out of Tibet’s distinct political status. Analysts have referred to this agreement as a blueprint of the PRC’s current “one country, two systems” formula, which has been applied to Hong Kong.

However, for the Chinese state, the desire to assimilate Tibet into the Chinese nation and thus strengthen its security took precedence over the actual implementation of the Seventeen Point Agreement. The promise of autonomy has rung hollow throughout the last 70 years, as Chinese authorities continue to make every important decision in the region.

Because Chinese security preoccupations remain dominant, Tibetans have engaged in steady resistance that has ranged from mass protests to self-immolations. One hundred and fifty-seven Tibetans have self-immolated since 2009, with the latest act by Yonten, a 24-year-old former monk from Kirti monastery in eastern Tibet, who set himself on fire on November 26, 2019.

For Tibetans, the annual commemoration of the signing of the Seventeen Point Agreement is a moment to challenge China’s legitimacy in Tibet.