Relations between the United States and China are as tense as they have been for decades. And nowhere is that tension more fraught than in the Taiwan Strait. This month historian Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang explains how the long-running dispute over the strait is rooted in the history of colonialism, decolonization, and competing ideas about national identity.

Mounting tensions in the Taiwan Strait pose perhaps the greatest security challenge in the world today. As political scientist Scott L. Kastner wrote in a recent book, “A war in the Taiwan Strait would have the potential to be a catastrophe of almost unimaginable proportions.”

The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) regularly projects its economic and technological power via a military show of force for its territorial claims in the South China Sea and the West Pacific—especially Taiwan. This development poses a threat not only to Taiwan’s security, but also to the security of Taiwan’s neighbors on the strategic First Island Chain, namely Japan and the Philippines.

Sitting behind Taiwan, Japan, and the Philippines is their longtime ally, the main hegemonic power and guarantor of peace in the Asia-Pacific region since the end of World War II, the United States.

The tension in the Taiwan Strait has risen considerably since 2016, and it shows no signs of easing up. Should it erupt into conflict the result would be a major shock to the world economy.

Even a blockade by the Chinese navy of the main maritime shipping routes and chokepoints surrounding Taiwan would put the entire global economy in disarray and for years to come. Estimates of possible losses differ, but they are in the tens of trillion dollars. For example, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) manufactures over 90 percent of the smallest and most advanced semiconductor chips are manufactured.

The Taiwan Strait conflict is not new. Since the early days of the Cold War, the world knew about the hostility between Taiwan and China and their jostling for representation and recognition internationally. The two states are still technically at war with each other, though this animosity has waxed and waned. There were, in fact, long stretches of stalemate and relative peace, and even times of vigorous trade, sociocultural exchange, and collaboration since the late 1980s.

Just as important as this Cold War narrative in understanding the complexity of the PRC-Taiwan tension, however, are issues of colonialism, decolonization, and nationalism.

The Cold War Comes to the Taiwan Strait

The pivotal events that led to the current conflict in the Taiwan Strait are widely known, namely, the Chinese Civil War and the ensuing Cold War in East Asia.

In late 1945, following Japan’s surrender in World War II, all-out war broke out between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the anti-communist Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, KMT) led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

When U.S. mediation failed, the Americans threw their support to the KMT. Seeing China as a key regional partner in the emerging global conflict with the Soviet Union, the United States helped introduce Nationalist China to the newly formed United Nations (UN) as a permanent member of the Security Council.

By late 1948, the tide of war turned against the KMT. Nationalist authorities in China collapsed in the following year. Frustrated by the unpopularity of Chiang’s regime, President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson stopped aiding the Nationalists.

Led by Chairman Mao Zedong, the CCP won the Chinese Civil War in 1949. The Chinese Communists toppled the Republic of China (ROC) that had been wrecked by decades of internal divisions, foreign incursions, and social upheavals.

The CCP established the PRC, the communist regime that still governs China. The losing side, the KMT government that had previously dominated the ROC on the mainland, fled to Taiwan.

Then the Korean War broke out in late June 1950. This devastating conflict between another two divided Cold War states in Asia became a watershed that shaped the geopolitics in the Taiwan Strait for decades. It reconnected the United States and the KMT/ROC against the CCP/PRC. Shortly after North Korea’s invasion of the South, Truman ordered the Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Strait to prevent an escalation of war in the region.

Washington refused to recognize the PRC diplomatically and touted the displaced ROC on Taiwan as “Free China,” the legitimate government representing the Chinese seat in the UN, in opposition to “Red China” on the mainland, an illegitimate usurper. It would be another two decades before Richard Nixon made the trip to Beijing to “normalize” the U.S. relationship with the PRC.

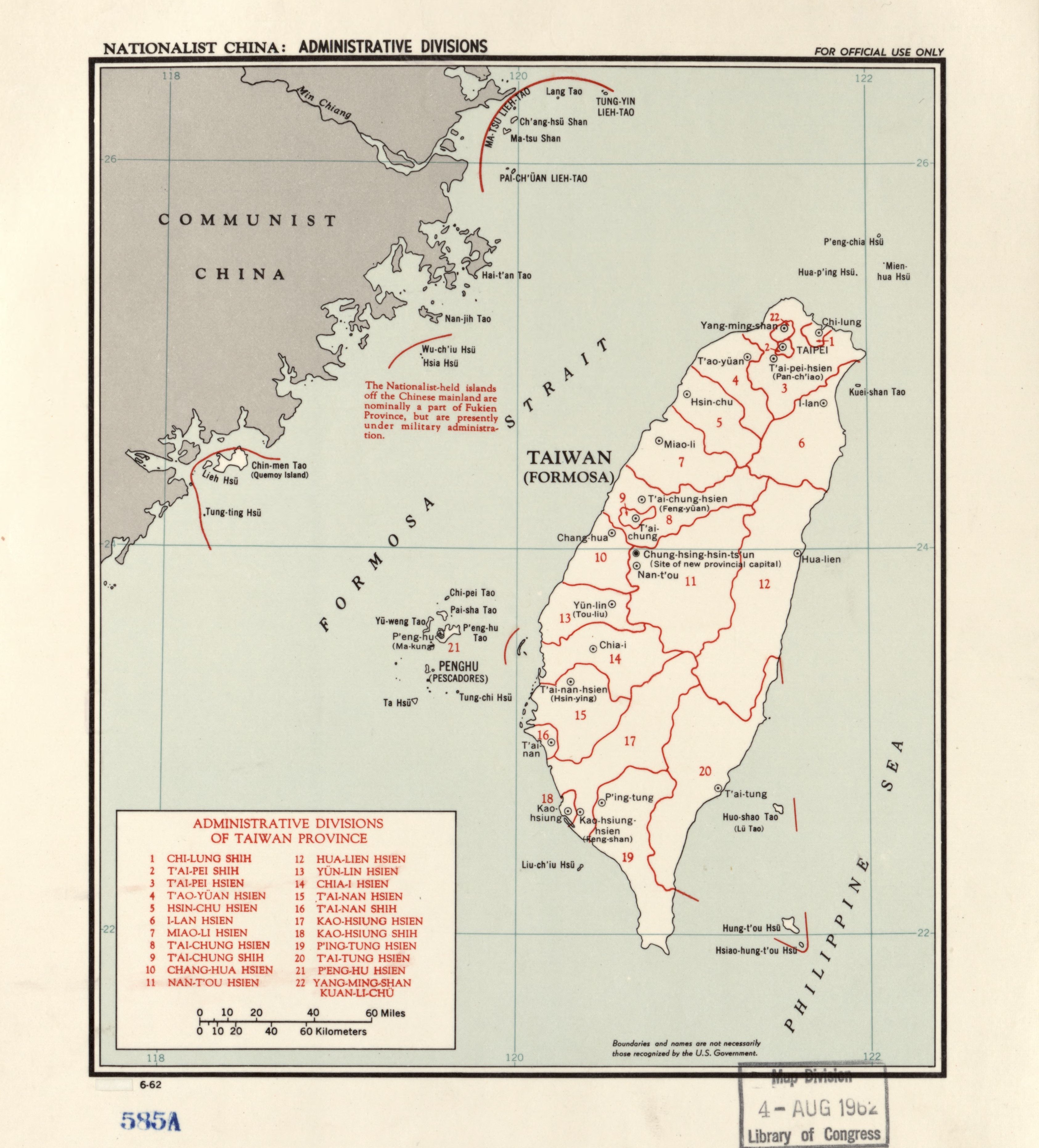

When the conflict in Korea ended in July 1953, the Chinese Communists turned their attention to offshore islands still held by the KMT: Dachen, Matsu, and Quemoy. The resulting clashes came to be known as the First Taiwan Strait Crisis (1954-1955) and the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis (1958). A mutual defense treaty between Washington and Taipei (KMT/ROC) was signed in late 1954 amid the first crisis.

To reduce the risk of starting another Korean War or even World War III, the Eisenhower administration tried to have the Generalissimo withdraw his troops from the offshore islands. Yet the Americans found the old Nationalist dictator a stubborn and intractable partner. They saw his single-minded determination to return his own regime to China as a serious threat to preserving peace and geopolitical balance in the West Pacific. Washington was successful only in getting the KMT off Dachen; Matsu and Quemoy are still held by Taiwan today.

The late 1950s and 1960s saw an easing of tension in the Taiwan Strait as the PRC was mired in the disastrous famine and massive social upheaval produced by Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Chiang secretly started military initiatives to invade the weakened PRC. These endeavors were quickly uncovered and stifled by his angry U.S. friends.

With the military option unattainable, the Nationalists concentrated their efforts on safeguarding Taiwan’s seat in the UN, maintaining the ROC’s status as the sole legitimate government representing China.

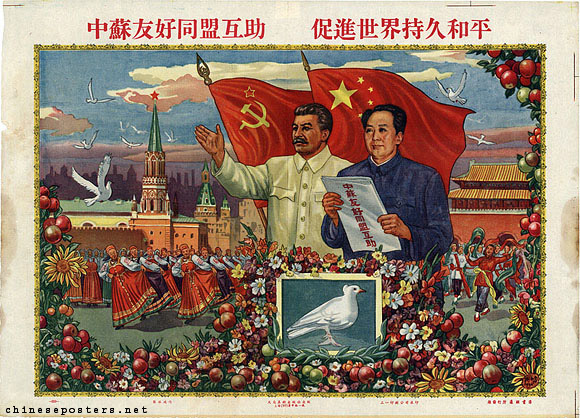

Most of the countries that recognized the PRC in 1949 were socialist states allied with the Soviet Union. Among major U.S. Cold War partners, only Great Britain established diplomatic relations with China in early 1950 (in order to preserve its colonial rule in Hong Kong).

The Sino-Soviet split constituted the next major watershed to transform Taiwan-U.S.-China relations and reshape the political configuration in the Taiwan Strait. In March 1969, an undeclared war erupted between the two socialist allies along the disputed Sino-Soviet border in northeastern China.

The split opened the door for Richard Nixon’s historic visit to the PRC in late February 1972, a trip facilitated by Nixon’s National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. The visit began the convoluted process of Washington and Beijing “normalizing” their relationship for the remainder of the decade, culminating on January 1, 1979, when the Carter administration formally recognized the PRC.

At the same time, Washington ended its treaty alliance and official relations with the ROC. The United States withdrew its military personnel and installations on Taiwan. It also promised to gradually reduce arms sales to Taiwan but without providing an end date for the sales.

The 1970s was also the decade that ROC/Taiwan began to lose its international presence, as nations in the world ditched Taipei and recognized Beijing one after the other. The avalanche started in late October 1971 when the UN member states passed General Assembly Resolution 2758 to expel the ROC delegates from the China Security Council seat, replacing them with delegates from the PRC.

From this point onward, the ROC/Taiwan not only ceased to represent China, it also ceased to be a political entity in a formal sense in the eyes of most countries in the world. The exceptions were the twenty or so nations that still recognized Taiwan by the late 1970s. That number is down to twelve in 2024, and the PRC obsessively polices other nations’ interactions with Taiwan.

Taiwan’s status thus became a perennial sore point between Washington and Beijing. In the 1972 Shanghai Communiqué and the 1979 Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations, the United States acknowledged the PRC’s position that there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China.

Yet the U.S. Congress also passed the “Taiwan Relations Act” (TRA) at the same time that the Carter administration established relations with Beijing. Under the TRA, the U.S. government would maintain de facto ties with Taiwan through the de facto embassy of the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT).

Dubbed “strategic ambiguity” by scholars and pundits, the American approach is intended to maintain peace and the status quo while encouraging cross-strait interactions that could contribute to a peaceful resolution in the distant future. It does so by deterring Chinese aggression with arms sales to Taiwan while discouraging the Taiwanese to move toward declaring de jure independence, which could provoke military actions from the PRC.

China’s View: Taiwan as a Puppet of U.S. Neocolonialism

CCP leaders in Beijing see the conflict over Taiwan through the lens of colonialism and decolonization. From Beijing’s perspective, Taiwan has been unjustly separated from the “motherland,” which robbed it of participating in China’s glorious socialist revolution and decolonization process in the mid-twentieth century.

This was mainly due to Washington’s “meddling” in the Chinese Civil War and American neocolonialism in Asia during the Cold War. Viewed in this light, the “great divide” of the two Chinese states since 1949 is an unnatural order of things, a monumental injustice committed against China by a discriminatory post-World War II international system dominated by the United States and its allies.

Even after the U.S.-China rapprochement, Washington continues to use Taiwan to thwart China’s rise and to preserve the so-called status quo. For the mainland Chinese, status quo means a continuation of Taiwan independence, an offensive and despicable situation that must be rectified. This thinking is drilled into the minds of most PRC citizens by the CCP’s anti-colonial and nationalistic education.

The shared feeling about Taiwan is strong and deeply emotional, etched into the collective psyche of the Chinese nation. The control of Taiwan has come to stand for China’s “great rejuvenation.”

The CCP leaders, starting from Chairman Mao and down to the incumbent Chairman Xi Jinping, have made Taiwan’s return to the motherland one of the regime’s most important historical missions. Only then can the Chinese Civil War officially end and, along with it, the historical injustice committed by China’s greatest competitor and rival, the United States.

Ironically, as the island evolved into a prosperous and progressive liberal democracy in the 1990s and the 2000s, its very existence has come to be seen as a threat to the political legitimacy and security of the CCP regime. This is especially true in light of Xi’s increasingly authoritarian and heavy-handed rule on the mainland.

The irony here is that democratized Taiwan no longer wants to attack China or undermine CCP rule, nor does it try to compete with Beijing internationally to represent the Chinese nation.

Nowadays, most Taiwan citizens and their democratically elected government simply want to be left alone to govern themselves in peace. The Taiwanese seek cordial and mutually beneficial relationships with other nations in the world, including the PRC. Regrettably, this independence is unacceptable for Beijing and a majority of Chinese citizens.

Anticolonial Struggle and the Formation of Taiwanese National Identity

This brings us to the last remaining piece of the puzzle in the Taiwan Strait predicament—Taiwanese national identity. The Taiwan identity is arguably the most crucial factor to consider in the rising strait tension in our time. Any sensible, ethical, and realistic solution to the Taiwan problem must take the thinking and local perspective of Taiwanese into consideration.

Yet the Taiwanese perspective has, until very recently, been largely neglected. This is because the outside world has understood the history of the Taiwan Strait mostly from the first framework of divided Cold War Chinese states.

When Chiang Kai-shek’s defeated army and government fled across the sea to Taiwan in 1949, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of civilian refugees, they did not move to an empty, uninhabited island. The approximately 1 million “mainlanders” exiled from China met roughly 6 million local Taiwanese residents.

Many of the local Taiwanese saw the Nationalist single-party dictatorship as a form of hegemonic, colonial dominance that suppressed Taiwanese aspirations for self-determination. They saw the displaced mainlanders (roughly 13 percent of Taiwan’s population) not as exiles and refugees, but as a privileged minority of colonizers.

Most local Taiwanese were ethnic Chinese who spoke the Hoklo or Hakka dialects. Notwithstanding Beijing’s claim that Taiwan has been part of China “since the ancient times,” large-scale Chinese settlements on the island did not take place until the seventeenth century under Dutch mercantile colonialism.

The early Chinese settler colonizers suppressed, intermarried with, and assimilated the indigenous Austronesian nations on the island. The latter saw their living spaces and communities dwindle. By the time the KMT/ROC relocated to Taiwan, indigenous peoples constituted only about 2 percent of the island’s population.

Between 1895 and 1945, Taiwan became an integral part of Japan’s imperial realm and its colonial expansion into China and Southeast Asia. When the Allied powers dissolved Japan’s overseas empire in 1945, Taiwan was returned to Nationalist China.

At first, the Japanized Taiwanese welcomed the new Chinese authorities with enthusiasm, hoping for emancipation, self-governance, and equal rights, the end to their colonial status.

Unfortunately, the islanders soon discovered that the KMT administration, contrary to its promise for democracy, equality, and (Chinese) brotherhood, was just another form of colonial exploitation, one that was far worse than the previous Japanese rule.

Angry Taiwanese soon rose up to protest in early 1947. An anti-government riot in Taipei erupted on February 28, an event that came to be known as the 228 Incident or 228 Massacre. Chiang Kai-shek, who was busy directing campaigns in China against the CCP, responded to the protests with a ruthless, punitive violence.

In the ensuing killings and arrests, thousands of Taiwanese elites and their families became victims of the KMT state. Following the purge, the Nationalists banned public discussion of the February 28 events, trying to erase this dreadful event from people’s collective memory.

State violence in Taiwan did not stop after the 1947 purge, however. The Generalissimo’s officials declared martial law on Taiwan in 1949. The KMT authorities would continue to hunt for CCP spies and sympathizers, political dissidents, and Taiwan independence activists throughout the next four decades, before political liberalization in the late 1980s.

This was the Nationalist “White Terror” on Taiwan. Tens of thousands were arrested, tortured, and jailed; many were executed in the 1950s. Free China was, in reality, not free. Taiwanese could only suffer in silence.

Things changed drastically in the 1970s.

The Nationalists faced a serious legitimacy crisis as their representatives were ousted from the UN and the regime’s biggest ally and backer suddenly became friendly with their sworn enemy in Beijing. The KMT lost support and credibility not only internationally but also at home among their own mainlander support base.

Among the older elites who had been Chiang Kai-shek’s most loyal followers, there was a prevailing sense of depression and disappointment. Their Taiwan-born children were also unhappy. They began to question the regime’s single-party dominance and silencing of critics.

In the meantime, the rapid development of the island’s export-oriented industrialization in the 1970s and the 1980s transformed Taiwanese society. It provided the previously suppressed and powerless local Taiwanese majority with wealth, confidence, and socioeconomic power.

By the late 1970s, the emboldened Taiwanese took to the streets to challenge KMT authority. They demanded the lifting of martial law, freedom of speech, and the end of the single-party dictatorship. Disadvantaged groups also protested for their rights: women, indigenous communities, disenfranchised KMT veterans, industrial workers, and farmers. The 1980s in Taiwan became a dynamic and vocal age of open demonstrations.

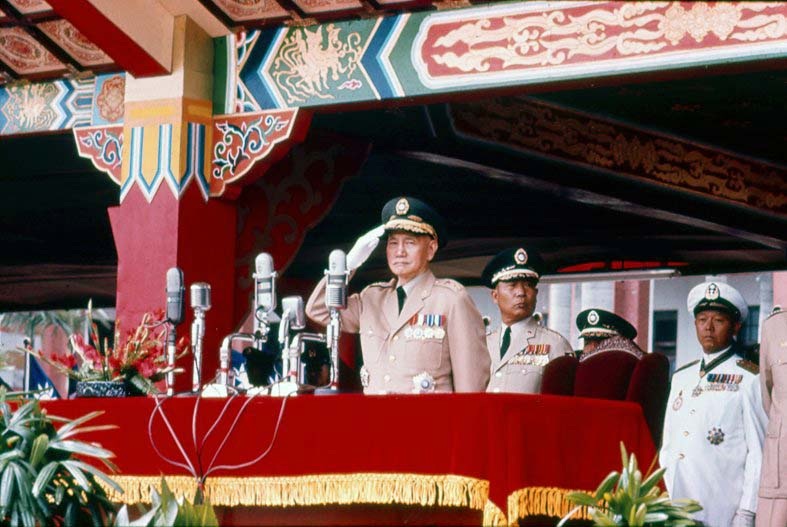

Chiang Kai-shek died in 1975. Faced with a revolting society led by the aggrieved Taiwanese majority, the Generalissimo’s eldest son and successor Chiang Ching-kuo adopted a more tolerant policy toward political dissent. Protestors and activists were still persecuted and jailed, but the extent of state surveillance and repression had lessened considerably compared to the worst days of the White Terror.

Ostracized by the international community and relying on the good graces of the U.S. Congress to uphold the TRA, the younger Chiang could no longer ignore pressure from his remaining allies in Washington to improve on the KMT’s deplorable human rights record in Taiwan.

The Generalissimo’s son is often lauded as a great visionary who had set the foundations for Taiwan’s democracy and contemporary relations with the PRC. What one really needs to understand is that the younger Chiang was compelled by circumstances to do so. A second-generation dictator from China didn’t just wake up one morning and decide that it was a good day to democratize and share power with the suppressed local Taiwanese majority.

The celebratory narrative of Chiang Ching-kuo overlooks the longstanding history of the local Taiwanese’s fight for self-determination against what they perceived as unjust autocratic rule and outside colonial domination.

This pursuit for freedom, autonomy, and justice played an instrumental role in the protest for democracy in the 1980s. The different historical trajectories between Taiwan and China help explain why one democratized and the other one has not, despite similar levels of modernization, economic success, and engagement with global capitalism.

In a strange twist, therefore, instead of seeing the KMT as its bitter foe, Beijing now sees Taiwan nationalism and the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) as even greater obstacles to unification.

Taiwan identity is, in a nutshell, the main source of tension between China and Taiwan in our time.

The more Taiwanese engage with the mainland society, the more they come to see the differences between Taiwan and China, and the more they come to appreciate their democracy and struggle for self-determination and international recognition, both in the past and present. This includes the second- and third-generation mainlanders. Many have traveled to China in search for their roots but end up realizing that their roots are actually in Taiwan.

The Taiwan Strait in Our Time: The Illusion of Unification

Ever since China’s rapprochement with the United States and its reform and opening under Deng Xiaoping, the CCP has proposed plans for peaceful unification under the “one country, two systems” scheme. The scheme has been rejected repeatedly by Taiwan but was later applied to the return of Hong Kong and Macau.

The so-called “1992 Consensus,” an alleged agreement reached between representatives from the reconciled CCP and KMT in 1992 about both sides sticking to the “one China framework” is also rejected by most voters in Taiwan today. If anything, the KMT and the CCP actually have different interpretations of “one China.”

There is, in fact, no consensus even between the two. The alleged agreement, if it ever existed, seems to be an expedient and face-saving pretext by the two old adversaries to start cross-strait interaction in the early 1990s.

Back then, China was underdeveloped and faced U.S. sanctions in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square Massacre. The CCP was trying hard to attract Taiwanese capital and talents. Hundreds of books and articles have been written on China’s economic miracle. What gets far less attention is the instrumental role played by Taiwanese investments, supply chains, and managerial know-how in China’s prodigious rise.

In the meantime, Beijing has refused to acknowledge the authenticity, historicity, and vitality of Taiwan national identity. Instead, PRC officials insist that this identity is manufactured by the Taiwanization policy of younger Chiang’s two democratically elected local Taiwanese successors, Lee Teng-hui (1988-2000) and Chen Shui-bian (2000-2008).

In 1996, the CCP leaders tried to intimidate the islanders not to vote for Lee, whom they thought was pro-independence despite being the KMT party chairman. The Chinese fired missiles and conducted military exercises in the strait. President Bill Clinton responded by sending two carrier groups to the waters near Taiwan.

This episode is known as the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. China’s belligerent tactic backfired. Lee won the election. The Chinese intimidation further strengthened the Taiwanese nationalist sentiment rather than weakening it.

Beijing also sent threatening messages when the first DPP president, Chen Shui-bian, took office in 2000. Not wanting to repeat the same mistake in 1996, the CCP refrained from taking military actions. They tried the carrot approach this time—wooing the Taiwanese economically.

For the next decade and a half, the PRC authorities concentrated on promoting cross-strait trade, investment, and socioeconomic integration. Taiwanese businesses and migrant skilled workers benefited tremendously from China’s rise but these interactions have not attracted the Taiwanese to unification.

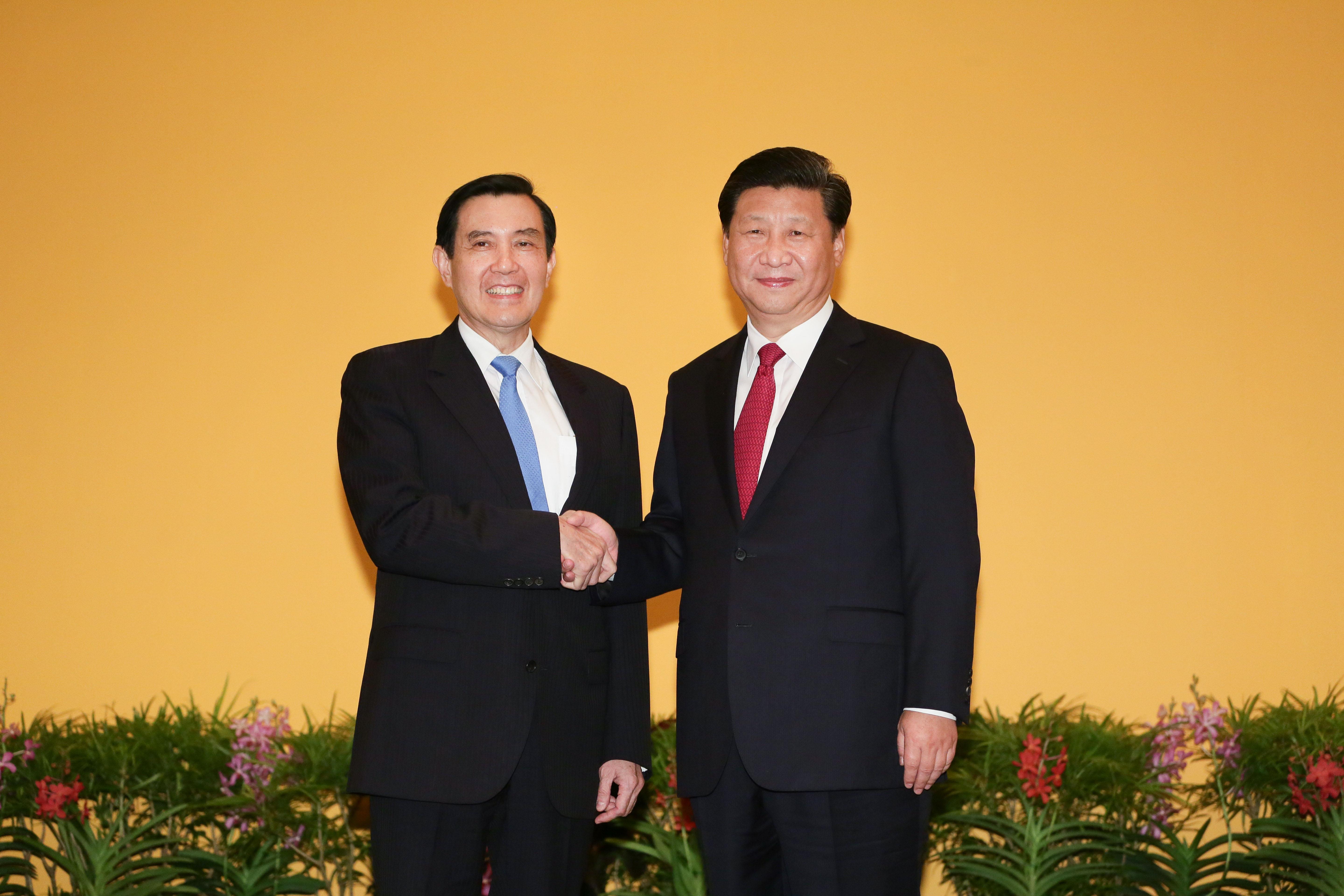

The electoral success of China-friendly President Ma Ying-jeou (2008-2016) did little to reverse the trend of Taiwanization. In March 2014, the KMT president tried to get the Taiwanese parliament to ratify a service trade agreement that his representatives had signed with the PRC. The agreement was controversial. It was negotiated in China and the proceedings lacked transparency.

Many Taiwanese thought that the terms could give Beijing enough economic clout in the island’s economy to jeopardize Taiwan’s sovereignty and political freedom. Ma’s attempt thus triggered a massive protest led by university students known as the Sunflower Student Movement.

In the aftermath, the agreement was not ratified. Further cross-strait economic integration was stalled. The service trade agreement debacle was a slap in the face to Ma’s negotiating partner, Chairman Xi Jinping.

It is thus not surprising that Xi decided to bring back the stick, and with a vengeance, when another DPP president Tsai Ing-wen was voted into office in 2016.

In January 2024, the Taiwanese elected Lai Ching-te (William Lai), Tsai’s vice president and previous running mate, another huge slap in the face to Xi and the CCP. Given the present circumstances, it seems that the tension in the Taiwan Strait will continue.

There are no easy solutions to the Taiwan issue. That said, having full knowledge of the diverse historical trajectories that have brought us to the current predicament offers much-needed perspective in the endeavors to formulate workable policies and maintain peace.

Brown, Kerry and Kalley Wu Tzu-Hui. The Trouble with Taiwan: History, the United States and a Rising China. London, UK: Zed Books, 2019.

Dawley, Evan N. Becoming Taiwanese: Ethnogenesis in a Colonial City, 1880s to 1950s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2019.

Easton, Ian. The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia. Arlington, Virginia: Project 2049 Institute, 2017.

Hsiau, A-chin. Politics and Cultural Nativism in 1970s Taiwan: Youth, Narrative, Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Kastner, Scott L. War and Peace in the Taiwan Strait. New York: Columbia University Press, 2022.

Lin, Hsiao-ting. Accidental State: Chiang Kai-shek, the United States, and the Making of Taiwan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Lin, Syaru Shirley. Taiwan’s China Dilemma: Contested Identities and Multiple Interests in Taiwan’s Cross-strait Economic Policy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Phillips, Steven E. Between Assimilation and Independence: the Taiwanese Encounter Nationalist China, 1945-1950. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003.

Rigger, Shelley. The Tiger Leading the Dragon: How Taiwan Propelled China’s Economic Rise. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf. Strait Talk: United States-Taiwan Relations and the Crisis with China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf (ed). China Confidential: American Diplomats and Sino-American Relations, 1945-1996. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Wang, Zheng. Never Forget National Humiliation: Historical Memory in Chinese Politics and Foreign Relations. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Wu, Jieh-min, translated by Stacy Mosher. Rival Partners: How Taiwanese Entrepreneurs and Guangdong Officials Forged the China Development Model. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022.

Yang, Dominic Meng-Hsuan. The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Modern Taiwan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021.