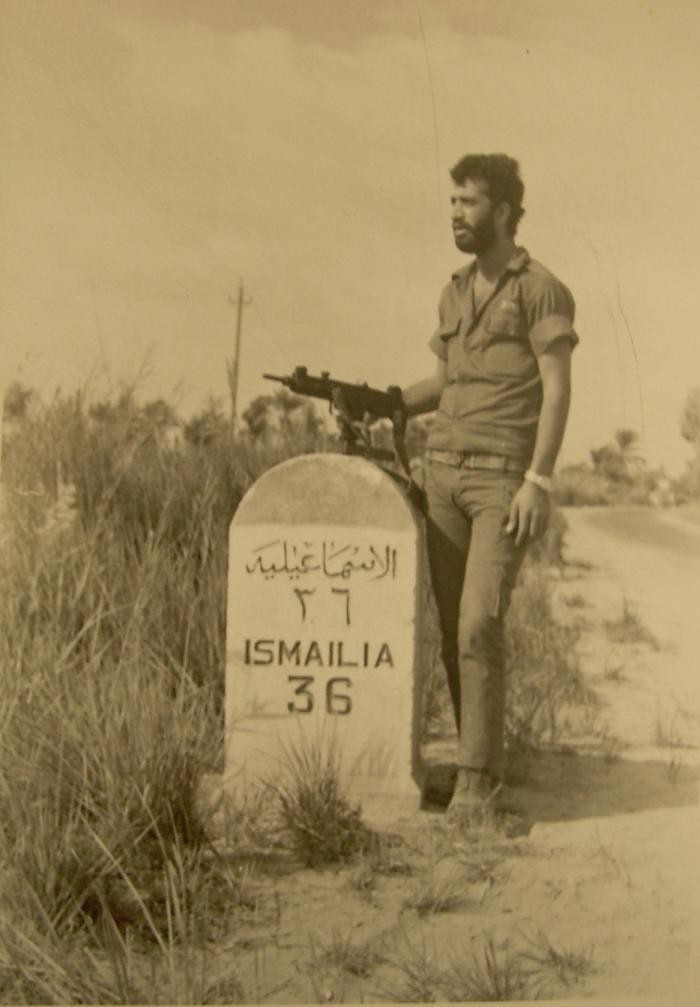

An Israeli solider stands guard on the road to Ismailia during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. As a new round of peace talks begin this month between Palestinians and Israelis, will this Washington-sponsored effort finally bring some measure of closure to the long struggle or will the attempt to find a two-state solution erupt again into open conflict, as it has so often throughout the 20th century?

In May, when an Israeli naval raid left nine self-described peace activists dead, commentators around the globe could scarcely stop themselves from saying "here we go again." Reports of violence and conflict between Israel and its neighbors are such regular occurrences in the news that they can have a numbing effect: the situation seems rooted in a tortured past and destined for a hopeless future. Leaders come and go, international mediation waxes and wanes and the disputes seem no closer to resolution. This month, as the Obama Administration attempts to restart the Israeli-Palestinian talks, historian M. M. Silver outlines the contours of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict across the last one hundred years. He reminds us that if the conflicts are of long-standing, the solutions have also been discussed for decades as well.

Readers may also be interested to see these two Origins articles: Tradition vs Charisma: The Sunni-Shi'i Divide in the Muslim World and The Meaning of 'Muslim Fundamentalist'.

In May, a six-ship flotilla originating in Turkey headed toward the Gaza Strip in an attempt to break the Israeli blockade of the area. The ships ignored Israel's demands to inspect the cargo they carried, and Israeli navy commandos boarded the vessels before the boats pulled into Gaza waters. Nine passengers affiliated with the Turkish Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief were killed in an altercation that again brought the world's attention to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and heightened international tensions.

The Gaza imbroglio has been the latest flashpoint in what seems an ongoing and never ending set of disputes, conflicts, aggressive actions, and violent clashes. It is also the most recent backdrop to current attempts to breathe new life into the Middle East peace process.

This month, the Obama Administration has restarted its efforts to broker a lasting peace between Israelis and Palestinians through a series of regular meetings, scheduled to begin September 14-15 in Egypt. As in previous efforts at peace, arriving at a peaceful solution will not be an easy task.

The conflict's causes are (it almost goes without saying) complex, combining conflicting land claims of rival nationalist movements, religious emotion, international strategic factors, and basic disagreements over the narrative of history.

Over the years, the geography of the conflict has shifted, never staying in one place for too long, and involving ever-shifting antagonists.

After Israel's establishment, as a result of a war in 1948, the country's dispute for the next quarter century was regional in character, and is best described simply as the "Israeli-Arab" conflict. The bewildering and embittering character of the dispute is reflected in the fact that from 1948 to 1973 Israel and Egypt fought four wars, and the Israel-Egypt fighting was just one of several theaters of the conflict.

Since 1973, it is most accurate to refer to the topic as the "Israeli-Palestinian" dispute, since all-out warfare between Israel and other Arab states abated, but violence between Israelis and Palestinians has at times reached agonizing levels. This was particularly true during the two Palestinian uprisings (Intifadas, 1987-1993 and 2000-2005) in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (territories conquered by Israel during the 1967 Six Day War).

Ostensibly a conflict between two nations, Jewish Israelis and Christian and Muslim Palestinians, for control of one land, the 1973-2010 phase of the conflict has sprawled north and south, from Lebanon to the Gaza Strip, and involved an array of secular and religious groups on the Arab side, such as the Palestine Liberation Organization, Hezbollah, and Hamas.

Although the causes and character of the recent, tragic clash involving the Gaza-bound flotilla remain in dispute, this much seems agreed upon:

In late summer 2005, Israel dismantled its settlements and withdrew from the Gaza Strip. Political control in this densely populated Palestinian area was subsequently won by Hamas, an Islamic movement beholden to a declared policy of opposing the existence of a Jewish state.

After Israel's withdrawal, militant groups used the Gaza Strip as a base to launch dozens of missile attacks against towns in Israel's southern Negev region. In retaliation, Israel launched its anti-terror "Cast Lead" military operation in winter 2008-09.

Its security concerns far from being allayed, Israel has enforced a blockade on the Gaza Strip for months. Middle East and European groups contend that this siege has precipitated a humanitarian crisis. And some activists, banded together in a "Free Gaza" movement, have organized ships in an effort to run Israel's blockade and bring supplies into the Gaza Strip. And then came the fatal shipboard altercation.

As Washington tries to bring the current antagonists together, they will face many obstacles to their efforts to hammer out to some sort of peace agreement: Israeli border security, the right of Palestinian return, the fate of Jerusalem, Israeli settlement in the Occupied Territories, the role of Hamas, and international pressures, among many others.

Yet, a central question facing the world as the Obama administration's talks begin is whether the "two-state" and "land-for-peace" solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which have been at the heart of so many previous efforts at peace, remain viable approaches.

A Prehistory of the Current Conflict

Most historians date the origins of the Israel-Palestine controversy to the era preceding World War I. It was then that a politicized Jewish national movement, Zionism, began to build an infrastructure for a Jewish state in the then Ottoman-controlled Palestinian lands.

What was the Middle East like before Zionism joined the neighborhood? The extent to which Jews and Muslims—and Judaism and Islam—coexisted in conflict or cooperation prior to the rise of Jewish and Arab national consciousness at the end of the 19th century remains an intriguing subject of historical discussion. But, a clear majority of Israeli and Palestinian historians agree that the fighting in the country for the past century or so is a new sort of historical phenomenon.

After World War I, the British took over the Palestinian lands under the neo-colonial "Mandate" system. And for three decades before 1948, when Israel became an independent state, Zionists had a measure of international support for their pioneering efforts, via the 1917 Balfour Declaration in favor of a Jewish "national home."

Arabs pointed to other promises and assurances given by the British during World War One; and they resisted Zionist state-building efforts in the country, perceiving them as outright colonial intrusion.

Though not uniformly organized, such Arab opposition became increasingly assertive. Uprisings in 1929 and 1936-39 were unmistakable indications of the depth and passion of the crisis in Mandate Palestine.

We will focus here on just one aspect of this fascinating pre-1948 period, due to its pertinence to current discussions of Israel and the Palestinian Authority: the origins of the "two-state" formula.

A two-state proposal was formally submitted by a 1937 British panel, in the "Peel" report. This specific plan for dividing the land among the two peoples was prefaced by a remarkably incisive prefatory analysis of the nationalist, religious, political, and economic causes of the dispute.

Thus, the idea of a compromise, splitting Israel/Palestine into two states for two peoples (and three religions) is far from a recent idea. Instead, it has been on the table for 75 years.

And, quite significantly, the Zionists agreed to the idea in principle both in 1937, and again a decade later when the United Nations endorsed a two-state partition plan (in both these instances, the Arab side flatly rejected the two-state formula).

Today, most Israelis would say that these past two-state proposals failed because of Arab intransigence, and this interpretation finds support in close studies of the diplomacy of the late British Mandate period. To this, Palestinians reply indignantly, "why is it 'intransigent' to oppose the partition of something that is already yours?" Equally true.

And here we come to the main point of comparison between the pre-1948 period and contemporary dilemmas—neither side, neither the Zionists nor the Palestinians, were happy with the specific details of the 1937 or 1947 proposal.

The 1937 Peel two-state plan, for instance, endorsed removing a quarter of a million Arabs from areas designated for an extremely small Jewish state. The fact that this would not have been the largest population transfer enacted on the globe during the interwar period hardly mitigates the humanitarian dilemmas posed by the specific contents of this serious peace plan.

Three quarters of a century ago the devil was in the details of a two-state solution. That adage holds true today.

1948 and the Stories People Tell

Then came the war of 1948.

How the different sides refer to the war is tremendously revealing. Israelis speak of the 1948 fighting as the War of Independence. They celebrate the victory as a miraculous underdog triumph of an embattled, small community warding off invading Arab armies, and ending 2000 years of Jewish powerlessness, the most gruesome manifestation of which was the Holocaust.

Indeed, for Israelis, the "War of Independence" conceptualization serves as moral and historical redress for the Holocaust. This basic perception of 1948 as near-miraculous redemption from the ruins of the Holocaust remains the way almost all Israelis see the war today.

For Palestinians, on the other hand, 1948 is referred to as "Naqba," meaning outright catastrophe, the dispossession of some 700,000 persons from their homes, and exile to refugee camps in Jordan, the Gaza Strip and elsewhere.

For decades, mainstream Israeli historiography interpreted this exodus of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees primarily in terms of internal Arab politics, Arab leadership, and Arab communal structure. Israeli histories either implicitly or explicitly denied that the new Jewish state bore any substantive culpability for the refugee issue.

The "Land for Peace" Formula: 1967 to the Oslo Accords

Together with the British Mandate pre-history and the 1948 war, the 1967 Six Day War is considered the third historical occurrence which "changed everything" in the Israeli-Arab dispute.

Perhaps the most important result of the 1967 war was the bringing of all of Jerusalem under Israeli control. After Israel's establishment as a result of the 1948 war, no event galvanized national feeling in Israel more than the unification of Jerusalem. It is an event that remains celebrated in songs, stories, and visual images known to any Israeli from the time he or she is first conscious of public events.

In the aftermath of its sweeping 1967 victory, Israel continues to be challenged by the question of how to deal with lands it conquered (including the Gaza Strip, West Bank, and Golan Heights).

Some lands won in the 1967 war have been returned to Arab sides. Most significantly, the Sinai Peninsula was given back to Egypt, under the late 1970s Camp David accords. The logic of these concessions came to be known as the "land for peace" formula.

For three decades, from the early 1970s to the first years of the 21st century, a significant portion of Israel's electorate (though not necessarily a majority) upheld this formula. They argued, often passionately, that the dispute with the Arabs would end when territories won in the 1967 war were conceded to the Palestinians to become the geographic basis of their state.

This viewpoint—the staple of the center-left in Israeli politics—gained the upper hand in the early 1990s, resulting from a confluence of local and global geopolitical factors, including the end of the Cold War, the first Palestinian intifada uprising, and the first Persian Gulf War.

From Israel's viewpoint, the ascendance of the left is the background to the dramatic 1990s Oslo peace process.

As a result of the Oslo initiatives (signed 1993), Israel accepted partial territorial concessions—areas on the West Bank are today under joint security and political control, and the Gaza Strip is controlled by the Palestinians, via Hamas. (Although Israel controls and monitors border crossings into Gaza, as does Egypt on the southern end of the Gaza Strip.)

In many parts of the world, this Oslo peace process rendered the two-state formula a familiar and legitimate concept. And—it is crucial to point out—Israel essentially endorsed this legitimization of the two-state formula. It formally acknowledged the PLO as the authentic representative of the Palestinian people, and then established an array of relations with the apparatus of the embryonic Palestinian state, called the Palestinian National Authority.

The problem is that while the Oslo process dramatically altered the political realities—and the map—of the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, it did not reinforce faith in the viability of the two-state solution as a remedy to a century of violence in the area.

Israel's political left is today in disarray, and very few people mention the "land for peace" formula without feeling a tinge of irony. For many, the formula is regarded with outright derision. That is because a series of territorial concessions made by Israel under the Oslo framework since the early 1990s did the opposite of achieving peace.

Horrific sequences of suicide bombings, and mass Hezbollah katyusha rocket attacks against a million Israeli citizens—Jews and Arabs—in Israel's north are just some of the catastrophes that have ensued since the land for peace formula was validated by the Oslo process.

That returns us to our starting point: the vast majority of Israelis, from the political right, center, and left, were appalled by the images and rhetoric connected to the recent Gaza blockade and flotilla controversy because they view the past generation of international diplomacy conducted under the land for peace formula as a betrayal, or even a semi-deliberate trick.

On the Gaza Strip, Israel did, in fact, sanction the "land for peace" policy. It dismantled all Jewish settlements, and withdrew its armed forces. Thereafter, it was bombed systematically by Hamas.

When it belatedly launched the Cast Lead military operation in winter 2008-09 to end Hamas bombardments, Israel was accused of possible war crimes by the United Nations.

Currently, "Free Gaza" peace activists from Turkey and Europe are attempting to cast themselves in the role of pro-Palestinian counterparts to the Holocaust survivors who tried to run the British blockade in 1947, aboard the famous "Exodus" ship and other vessels, and make a home for themselves in the new Jewish state.

Such comparisons are, to Israelis, invidious, and they completely undermine faith in "land-for-peace" diplomacy. As they see it, their country conceded land, and then received not peace, but rather missile attacks, insulting Holocaust analogies, and shrill war crime accusations.

Jerusalem: Starting Point or Endgame?

Where does this leave the present and near future of the Israeli-Palestinian dispute?

The most immediate, and extremely serious, obstacle impeding hopes for any Obama administration initiative on the Israeli-Palestinian issue derives from tactical mistakes made both by American and Israeli leaders in recent months, particularly on the issue of Jerusalem.

Contrary to much rhetoric and breast-beating around the world, the Jerusalem issue is not insoluble (and the Jewish nationalist movement, Zionism, has displayed rather more flexibility on the issue than many groups around the world, including American Jews, seem to believe).

However, the Obama administration badly miscalculated when it focused earlier this year on Jerusalem as a fulcrum to re-start talks between the sides, and pressure Israel.

Similarly, Israel's government under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu took a number of missteps in past months, providing ammunition to forces around the world that insist on branding various Jerusalem neighborhoods as Israeli "settlements" (like any other "settlement" in the occupied West Bank), a perception that is not shared by the vast majority of Jews who live in Israel.

Neither the most complicated nor least resoluble issue in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Jerusalem is, without doubt, the topic that ought to be addressed at the end of a viable peace process. Emotions stirred by the holy city are powerful, and clearly complicate relations between the sides when they are aroused, in the absence of shared commitments to peacemaking.

Jews, of course, regard the city as the sole, unique center of their religious-national tradition, and as the capital of Israel. The right to expand and develop Israel's capital is, for virtually every Jew who lives in the country, assumed to be fundamental and inviolable. This being the perception, very few Israelis would regard the building of a Jerusalem neighborhood on the other side of the 1967 lines as "settlement" activity.

More generally, Israel's settlement movement on the West Bank is an outgrowth of one particular branch of the Jewish nationalist movement, religious Zionism. The religious Zionists conceptualize Israel's right to exist, and (more to the point) its right to various parts of the country, in Biblical terms that are not shared by all Israelis.

In contrast, many Israelis consider themselves heirs to a secular national tradition that conceptualizes the Jewish state in cultural and political terms. These secular Zionist terms do not include a claim of divine right to land. For them, and for many observers both within and outside Israel, the religious Zionist settlement movement remains controversial.

Jerusalem, however, is a consensus issue for all streams of Zionism, whether religious or secular.

Looked at from the Palestinian point of view, Jerusalem is home to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who see no reason to accept Jewish sensibilities and claims regarding the city. Israelis (and others) sometimes deride Islam's stake in the city, regarding it as "only" the third most important site to Muslims, following Mecca and Medina, but this is hardly a compelling interpretation.

It is unduly dismissive both to the show of devotion which can be seen in Friday prayers on Haram al-Sharif (the Temple Mount), the site of Muhammad's night journey, and also to the enormously powerful role Jerusalem has played as a rallying point of Palestinian national emotion in many turning points of the conflict, from the 1929 uprising to the start of the Second Intifada in 2000.

However one wants to sort out religious sensibilities regarding Jerusalem, it is undeniable that in sections popularly known as the "Eastern" part of the city, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians dwell as a religious-national enclave disconnected in obvious ways from the rest of the city, notwithstanding all of Israel's post-1967 discussion about Jerusalem's unification.

For these Palestinian Jerusalemites, new Jewish neighborhood initiatives sponsored by Israel's government have the same character as settlement construction on the West Bank, since they propose erecting small Jewish enclaves in the middle of a populated Arab area.

In objective fact, some Western reporting about Israeli plans to "plant a Jewish neighborhood in a crowded Palestinian neighborhood" can be misleading and over-stated.

Yet, the important parameter in the dispute is the way the antagonists feel, rather than "plain facts." And it is also the case that ultra-nationalist Jewish groups in Israel would, in the absence of government restraints, pursue aggressive construction plans in ways that would furnish empirical justification of this particular Palestinian concern.

Going Forward toward Peace?

So does all of this history mean that the Israeli-Arab dispute is preordained to flounder because of the Jerusalem (or some other) issue, and the mass of monotheistic tension it can arouse?

One does not have to blindly endorse every move Israel has made in its capital since 1967 to realize that there have been restraints and continuing displays of respect to Muslim and Christian sacred sites—beginning with Defense Minister Moshe Dayan's immediate order to remove Israeli flags from the golden Dome of the Rock, in the climactic moment of the 1967 war.

Apart from security dimensions (that become important on Fridays, during periods of violence), access to the holy sites on Haram al-Sharif is controlled by the Waqf Islamic trust.

Much more important than these daily arrangements (which, I admit, many Palestinians might not consider particularly liberal) is the fact that there is ample historical precedent supporting the possibility that Israel, under the right conditions, could accept some sort of negotiated arrangement on the Jerusalem issue in a peace deal.

As we have seen, before Israel's establishment, a two-state solution was twice proffered under organized international circumstances to the two sides. Under each plan, the 1937 partition proposal offered by the British, and the 1947 UN partition proposal, Israel's presence in Jerusalem was extremely limited—and yet the Zionists accepted both plans.

I bring up these historical examples not as a suggestion that Israelis in 2010 would be willing to surrender sovereignty in their capital—and return to the internationalization schemes for Jerusalem broached by the British and the United Nations before 1948—but rather as a hint that Israeli pragmatic realism can extend to Jerusalem, as it can to any other issue, when circumstances are propitious.

The Obama administration's error in winter-spring 2010 was to expect such pragmatism at a time when years of Hamas terror, Iranian nuclear posturing, and a general lack of political cohesion in the Palestinian Authority have left far too many Israelis scratching their heads in doubt about the viability of diplomatic peacemaking.

The Obama administration has acted like an architecture professor who expects students in a first year class to present designs for a complicated city project whose consummation actually would require years of confidence-building and apprenticeship.

Jerusalem is the endgame issue.

Do all of these considerations point to a bleak, or even apocalyptic, future? Certainly not. While we have in this article focused on stumbling blocks to peace, it is also important to realize that realities in the dispute have changed dramatically in the past two decades, not uniformly in one "bad" or "good" direction.

Less than 20 years ago, Israel viewed the PLO as a terror organization, and punished some of its citizens for initiating talks with PLO members. Today, the most promising discussion route to be pursued by American mediators such as George Mitchell and Hillary Clinton features the Fatah (PLO) regime on the West Bank, controlled by Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen).

In other words, the PLO has transformed from the ultimate enemy of Israel to its most viable possible discussion partner.

Palestinians have experimented with self-rule in the territories for fifteen years, more or less. Those experiments have, admittedly, spawned Hamas militants who are inimically opposed to Israel and to any possible peace process. But it has also entrenched figures like Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, who has impressed many Western commentators as a promising player for any future two-state framework.

To my mind, these and many other developments are causes for caution when prognosticating about a dark future for Israeli-Palestinian relations. After all, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is now about as old as the Cold War was when the Berlin Wall came down, and no one predicted that event.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Religions of the Middle East

Benny Morris, Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949

Benny Morris, A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001

Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness

Leslie Stein, The Making of Modern Israel, 1948-1967

Shlomo Avineri, The Making of Modern Zionism

Yoav Gelber, Palestine 1948: War, Escape and the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem

Baruch Kimmerling, Joel Migdal, The Palestinian People: A History

Edward Said, The Question of Palestine

Dennis Ross, The Missing Peace: The Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace

Peter Hahn, Caught in the Middle East: U.S. Policy toward the Arab-Israeli Conflict

Michael Oren, Six Days of War