In July 1956, the international order was disrupted by the Suez Crisis, a complicated imbroglio marked by the intersection of European decolonization, the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Cold War, and the growth of U.S. power. The emergency culminated in October, with a war in Egypt that briefly threatened hostilities on a global scale.

The crisis began on July 26, when Egyptian Premier Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal Company after the United States and Britain refused to provide his country economic aid. Nasser seized the British- and French-owned firm not only to avenge the Anglo-U.S. denial of economic aid, but also to demonstrate his independence from the European colonial powers and to garner the profits the company earned in his country.

Egyptian supporters cheer President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

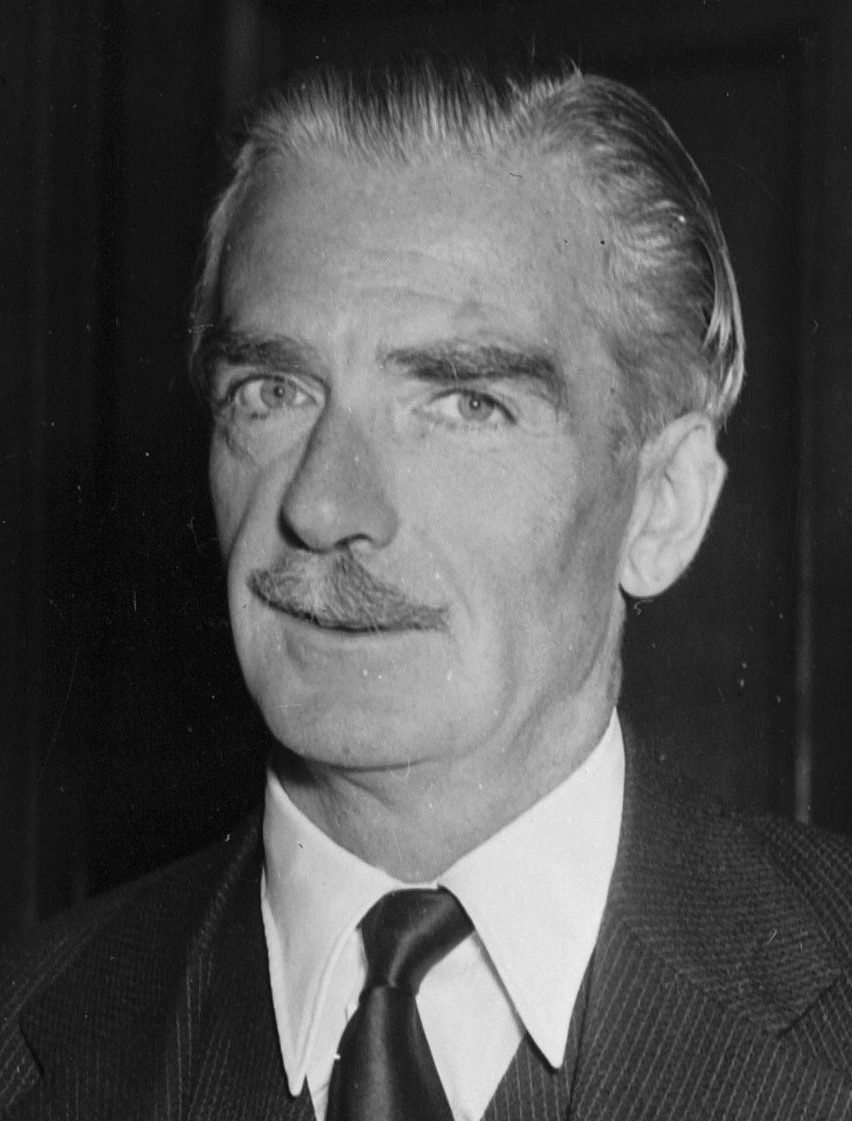

British and French leaders threatened to use force to compel Nasser to restore their control of the canal company. Citing the importance of the maritime trade that plied the waterway and the profits the Western governments earned from operating it, British Prime Minister Anthony Eden observed that “the Egyptian has his thumb on our windpipe.”

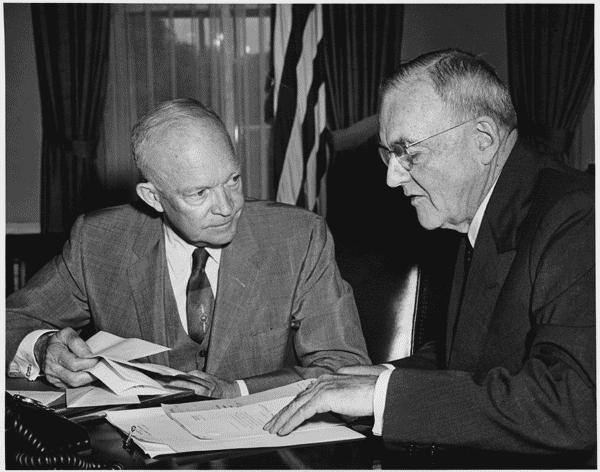

During the ensuing three-month stand-off, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sought to avert a military clash and settle the canal dispute with diplomacy. He feared that an Anglo-French military strike would spawn anti-Western nationalism across the region and give the Soviet Union an opportunity for political gain.

Eisenhower directed Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to defuse the crisis through public statements, negotiations, two international conferences, establishment of a Suez Canal Users Association (SCUA), and deliberations at the United Nations. By late October, however, these efforts had proved fruitless, and Anglo-French preparations for war continued.

Meanwhile, Great Britain and France secretly colluded with Israel to launch a tripartite attack on Egypt. Under the plan, Israel would invade the Sinai Peninsula, while Britain and France would issue ultimatums ordering Egyptian and Israeli troops to withdraw from the Suez Canal Zone.

Prime Minister Guy Mollet and Foreign Minister Christian Pineau made fateful decisions for France.

When Nasser (as expected) rejected the ultimatums, the European powers would occupy the Canal Zone and depose Nasser. Under this ruse, Israel invaded the Sinai on October 29. Within days, Israeli forces approached the Suez Canal and the European powers issued the contrived ultimatums and launched air strikes against Egypt.

U.S. officials failed to anticipate the collusion scheme before Israel initiated hostilities.

Israeli troops during the battle for the Sinai.

They were distracted by a war scare between Israel and Jordan as well as by anti-Soviet unrest in Hungary, and by the impending U.S. presidential election. They also believed the assurances of friends in the colluding governments that no attack was imminent.

Although caught off-guard by the outbreak of hostilities, Eisenhower took steps to end the war quickly. He imposed sanctions on the colluding powers, achieved a UN ceasefire resolution, and organized a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to disengage the combatants.

Yet before Eisenhower’s diplomacy had effect, the crisis moved into a dangerous phase. British and French paratroopers landed along the Suez Canal on November 5 and Soviet leaders threatened to intervene in the fighting and to retaliate against London and Paris with weapons of mass destruction.

Britain’s 6th Royal Tank Regiment rolling ashore at Port Said, Egypt in early November 1956.

Intelligence reports that Soviet forces were concentrating in Syria for intervention in Egypt alarmed U.S. officials, who sensed that the turmoil in Hungary had left Soviet leaders prone to impulsive behavior.

Prudently, Eisenhower ordered the Pentagon to prepare for world war even as he increased pressure on the colluding powers to desist. Shaken by the sudden prospect of global conflict, the president also moved quickly to avert it. He applied political and financial pressures on the belligerents to accept, on November 6, a UN ceasefire deal that took effect the next day, and he endorsed efforts by UN officials urgently to deploy UNEF to Egypt.

Peacekeepers of the United Nations Emergency Force deployed in the Sinai.

Once the ceasefire took effect on November 7, tensions gradually eased. UNEF soldiers arrived in Egypt on November 15 and were positioned between the belligerents. British and French forces departed Egypt in December, and Israeli forces withdrew from the Sinai in March 1957. UNEF troops remained in Egypt as a buffer against Egyptian-Israeli hostilities until Nasser ordered them to leave in May 1967.

The Suez Crisis had a profound impact on the balance of power in the Middle East and on the responsibilities that the United States assumed there. It tarnished British and French prestige and authority among Arab states and hastened the pace of European decolonization in Africa and Asia. It also led to the resignation of Prime Minister Eden in January 1957.

Nasser, by contrast, not only survived the ordeal but secured a new level of prestige among Arab peoples as a leader who had defied European empires and survived a military invasion by Israel. The region’s remaining pro-Western regimes seemed vulnerable to Nasserist uprisings. Although Nasser showed no immediate inclination to become a client of the Soviet Union, U.S. officials feared that the Soviet threats against the European allies had improved Moscow’s image among Arab peoples.

The Suez Crisis instigated a new level of U.S. involvement in the Middle East. Concerned by the decline of European influence and rise of Soviet involvement, the United States declared the Eisenhower Doctrine in early 1957, pledging to distribute economic and military aid and, if necessary, use military force to contain communism in the Middle East.

Damage to Port Said following Anglo-French Bombing, 1956.

Under the Eisenhower Doctrine, the U.S. government immediately dispensed tens of millions of dollars in economic and military aid to Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Libya. The doctrine guided U.S. policy toward political crises in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon in 1957 and it provided the foundation for U.S. military intervention in Lebanon in 1958.

The Suez Crisis stands as a watershed event in the history of Middle East diplomacy. By undermining traditional Anglo-French hegemony, exacerbating the problems of revolutionary nationalism personified by Nasser, stoking Arab-Israeli conflict, and offering the Soviet Union a pretext for penetrating the region, the crisis drew the United States toward substantial, significant, and enduring involvement in the Middle East.