The Napoleonic Wars are remembered primarily as European affairs, and for good reasons. The wars and the politics around them led to sweeping transformations in warfare and politics throughout nineteenth-century Europe, and the most iconic battles, such as Austerlitz, Trafalgar, Borodino, and Waterloo, all occurred either in Europe or close to it.

But Alexander Mikaberidze’s The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History challenges readers to view these wars and their impact in a much broader geographical context. While not all readers may agree with Mikaberidze’s claim that the Napoleonic Wars had a greater long-term impact outside Europe than in it, he nevertheless makes a compelling case for viewing these wars as events of truly global significance.

Though the purpose of The Napoleonic Wars is to illustrate the significance of events outside Europe, Europe nevertheless plays a large part in Mikaberidze’s story. Understanding that the global history of the Napoleonic Wars cannot be fully understood without also explicitly linking it to events in Europe, Mikaberidze begins his work with a detailed explanation of the French Revolution and its background before getting into the Napoleonic Wars themselves.

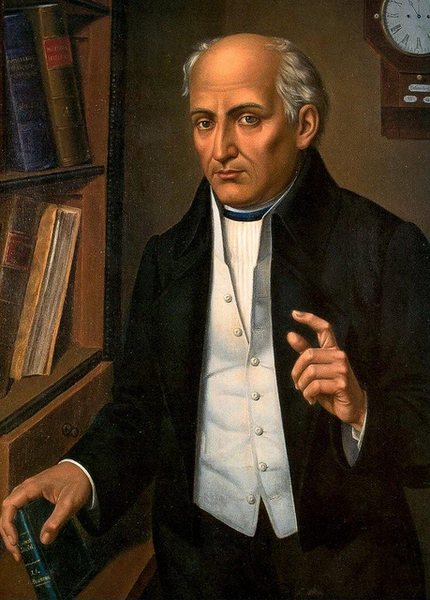

Miguel de Hidalgo y Costilla, leader of a popular revolt against the colonial government in Mexico and a key figure in the Mexican War of Independence. Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1808 disrupted central control over Spain’s colonies in Latin America, which presented an opportunity for Hidalgo to seek greater autonomy in the colonies.

The book follows a roughly chronological structure, but in order to present a more cohesive narrative for certain regions, Mikaberidze does some occasional backtracking. This structure works relatively well. Mikaberidze delves deeply into events in Europe and then seamlessly transitions to a discussion of how they affected the rest of the world in a breathtakingly wide span of case studies ranging from Chile to Japan.

These case studies illustrate that the Napoleonic Wars exerted an extraordinary amount of influence outside Europe. Some of the most significant examples took place in the Americas. Napoleon’s invasion of Spain and the sudden collapse of Spanish royal authority in Spanish America created a power vacuum that encouraged communities throughout the colonies to redress local grievances and eventually declare their independence.

Meanwhile, Napoleon’s machinations that resulted in the Louisiana Purchase considerably strengthened the young United States. Additionally, the Purchase contributed to the rise of Manifest Destiny and the defeat of the Native Americans by removing the French and Spanish colonies along the Mississippi as an obstacle to the United States’ westward expansion. British victories against France and its allies in India laid the groundwork for Britain’s later domination of the subcontinent, while Russia’s success in the Baltic broke the power of Sweden.

But Mikaberidze also makes a good case for sweeping changes within Europe. While the Napoleonic Wars led to few significant border changes in the short term, the long-term impacts within Europe were immense. The formation of the Confederation of the Rhine and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire laid the groundwork for the eventual unification of Germany.

Nationalism, spread both by and in reaction to the French, irrevocably changed the face of European politics. Britain’s naval and colonial victories, while they clearly had overseas effects, also ensured that Britain would dominate Europe economically for roughly the next century. And all of this is to say nothing of the extensive military reforms that occurred throughout Europe during the decades of fighting that began shortly after the French Revolution.

One of the key themes that emerges from Mikaberidze’s work is that the geopolitics of the Napoleonic Wars were in fact very similar to those of the pre-revolutionary era. Though it has long been assumed that France’s enemies were primarily threatened by French Revolutionary ideology and sought to prevent this ideology from gaining traction in their own countries, Mikaberidze makes a convincing case that the real reason the other European powers felt so threatened—especially after Napoleon seized control of France—was the strength of the French armies.

The French military reforms of the 1780s through 1805 meant that the French army now posed a serious threat to the European balance of power. In many ways, Mikaberidze posits, while the domestic politics might have changed, the geopolitics of the Napoleonic era would have been quite familiar to Louis XIV. In fact, Mikaberidze argues that one of the defining features of this era was the continuation of the ongoing struggle for supremacy between France and Britain.

This Franco-British power struggle is at the core of many chapters, especially those that deal with issues outside Europe. While Napoleon is often portrayed as being an uncommonly aggressive and duplicitous dictator, Mikaberidze argues that the British were just as aggressive and duplicitous as he was. This comes through most clearly during his discussion of the brief Peace of Amiens period of 1802-1803. According to the orthodox view, the peace collapsed due to Napoleon’s policies, but Mikaberidze argues that not only did Britain want to return to hostilities, but any responsible French sovereign could have hardly pursued different policies from those Napoleon did.

Another key theme in Mikaberidze’s work is the persistent divisions among France’s opponents, which seriously hampered the effectiveness of anti-French coalitions. The importance of these divisions is fairly well-known in the European campaigns, particularly in 1805-1806, but Mikaberidze points out that the anti-French powers were even more divided outside Europe.

This was most notable in their dealings with Iran and the Ottoman Empire, where Britain expended nearly as much effort to counter Russian influence as it did to oppose the French. In this way, Mikaberidze argues, the famous “Great Game” that pitted Russia against Britain in Asia throughout much of the 19th century began during the Napoleonic Wars as a three-way contest between France, Russia, and Britain.

Overall, Mikaberidze makes a powerful case for the global influence of the Napoleonic Wars, but given that their influence in Europe was also so significant, it is hard to simply accept that the wars’ global influence was greater than their European influence. This does not in any way reflect poorly on Mikaberidze’s work. The book is far stronger for discussing both in such depth and its success or failure does not rest on the reader’s acceptance of this argument.

The one notable blemish in the work is the confusing discussion of the costs of the wars in the final chapter. The reader is deluged in casualty statistics—some of which seem mutually contradictory—without a real sense of why these statistics are given for some battles or campaigns but not others. But this is one small part of one chapter, and on the whole, the work is focused and enjoyable.

It is easy to recommend The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History for Napoleonic scholars. Some material may be familiar to experts already, but Mikaberidze’s chapters on events outside Europe are worthy of reading in their own right. Casual readers, except those with a real interest in the Napoleonic era, may struggle given the book’s scope and length—the main text, excluding notes, comes out to 642 pages. But anyone prepared to tackle a lengthy work will be richly rewarded for their efforts.