In the past several months, former Turkish Prime Minister and current President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has made international headlines for statements about the roles and rights of women in Turkey, for constructing a massive new presidential palace, and for arrests of journalists. Some opponents worry that Erdoğan intends to impose his brand of Islamism on the long-secular Turkish political system. This month, historian P. Scharfe reminds us that Erdoğan’s agenda also involves fundamentally rewriting the Turkish constitution to create a powerful presidency in place of its traditional figurehead role. To understand where the Turkish political system might be headed under Erdoğan requires us to understand the historical forces and military coups that have shaped it.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on the Middle East: Istanbul and Turkish Politics;Atatürk; Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; the Alawites and Syria; U.S.-Iranian Relations; U.S.-Iraq Relations; and The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Listen to this History Talk podcast on the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

With his election as president of Turkey in August of 2014, the spectacular career of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has entered a new phase, and the same could be true for the “New Turkey” he has proclaimed.

After 11 years as Turkish prime minister and head of the ruling Justice and Development Party (known by its Turkish acronym AKP), Erdoğan’s staying power as the leader of Turkey is remarkable in a country long plagued by political instability and successive military coups. Perhaps more notably, he has begun to successfully challenge the ideological basis of the Turkish Republic since its founding in 1923: the uncompromising secularism of the first Turkish president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Although Erdoğan insists that he is committed to secularism, he has won the hearts of millions of conservative and religious voters with subtle and overt appeals to Islamic identity, from restrictions on alcohol and abortion to the lifting of restrictions on the Islamic headscarf. He has achieved unprecedented levels of electoral support, aided also by perceptions of good economic management.

Now, with a declared intention to act as a powerful president, Erdoğan’s political authority may reach an entirely new level, and his ambitions are symbolized by the recent construction of a grandiose, 1100-room presidential palace .

There is only one caveat: Erdoğan will have to overhaul the Turkish constitution before he can transform the traditionally weak presidency into a position from which to dominate Turkish politics.

|

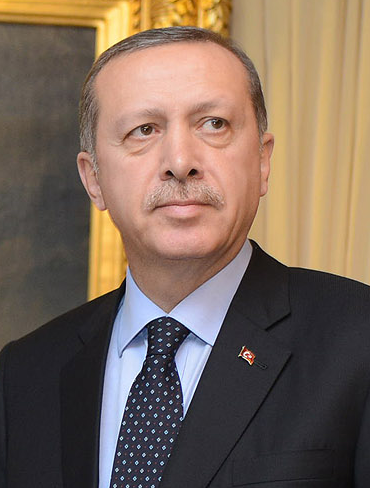

| Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

This prospect deeply worries his opponents and not without some justification.

Political scientists generally argue that presidential systems are more vulnerable to authoritarianism than party-centric parliamentary systems like Turkey has had up to this point.

More specifically, Erdoğan’s consistent electoral success has generated increasing opposition toward his government by those outside his political base. For many years, Turkey’s secularist opposition has decried Erdoğan not only for allegedly having a “secret” Islamist agenda, but also for prosecuting oppositional journalists, bureaucrats, and military officers on politicized charges.

Even among intellectuals of a moderately religious bent, opposition toward an ever more self-confident Erdoğan is growing. Moderate supporters had previously seen Erdoğan as a useful foil to Turkey’s “deep state”—a union of authoritarian generals, judges, and government bureaucrats who have, until recently, guarded the status quo in Turkey—but less so recently.

Most notably, a longstanding entente between the AKP and the moderate religious group known as Hizmet (“Service”) led by Fethullah Gülen was shattered in 2013 when Gülen-linked prosecutors uncovered evidence of corruption in elite AKP circles. Since then, the conservative journalists of Zaman—Turkey’s leading newspaper, owned by Fethullah Gülen—have become quite critical of Erdoğan. In retaliation, Erdoğan’s government arrested at least 23 Gülenist journalists in late 2014, including some at Zaman.

The extent of political power wielded by Erdoğan as president has now become a primary question of public debate.

Turkish presidents since World War II have normally taken a low profile due to Turkey’s parliamentary system (as defined and redefined in successive constitutions). In contrast to presidential systems like that of the United States, the Turkish prime minister holds most of the legislative and executive power, while the presidency has recently been more of a ceremonial post “above politics.”

For example, the outgoing president Abdüllah Gül, an AKP co-founder and one-time intra-party rival to Erdoğan, did not oppose a single parliamentary bill in his seven years as president.

However, the “New Turkey,” Erdoğan has vowed, will have “new customs,” and he insists that concerns about presidential power are emanating only from “non-democratic elements.”

He is ready to amend the Turkish constitution to create a stronger presidency, an act that would require only a handful of votes beyond his own party’s current parliamentary majority. Of course, this would still require striking some kind of a deal with one of the other parties, which are likely to oppose him.

But such an attempt would be aided by the deep illegitimacy of the existing Turkish constitution, which was written in the wake of Turkey’s last and most violent military coup. There is in fact broad agreement that the current constitution, drafted at military behest in 1982, must be replaced. Concerns about this document’s failure to guarantee basic civil rights are shared across the Turkish political spectrum.

Thus, the political showdown which is sure to come—and will almost certainly remake the very essence of Turkish politics—must be understood against the backdrop of the long and fraught history of constitutions in Turkey.

Erdoğan’s dreams of presidential power would not be plausible at this moment without the bitter memories of past constitutions’ military origins. To the AKP faithful, unelected and secular-leaning “deep state” institutions, tainted by association with past coups, must be brought to heel by a powerful elected president, namely Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Constitution-Making and Presidential Power in the Early Republic

The current discussions over constitutional reform are nothing new. Turkey’s constitution has been overturned several times in the years since the country’s founding in the wake of World War I and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. And debate over the constitution has been a consistent characteristic of Turkey’s political history in the twentieth century.

With Istanbul under Allied occupation in 1921, an ad hoc national assembly in Ankara—the inland city which became Turkey’s new capital—passed a “Fundamental Organization Law” (Teşkilat-i Esasiye Kanunu), the predecessor to the Turkish Republic’s first constitution.

Although it was not dictated to the assembly by force, the animating spirit behind this document was a military officer named Mustafa Kemal (not yet called Atatürk, or “Father Turk,” as he would be later known), who had been a successful World War I general and was still nominally serving the Ottoman government.

Rather than being a full constitution, the Fundamental Organization Law of 1921 was a temporary expedient intended to facilitate military resistance against the post-war order dictated by the Allies. It was therefore Mustafa Kemal’s nationalist army that held the real power, not the fledgling national assembly.

|

| Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Founder of the Turkish Republic |

In 1923, Turkish nationalist efforts to revise the post-war peace terms and to assert Turkey’s national sovereignty were crowned by the Treaty of Lausanne, which recognized the new Republic of Turkey. As a result, the young republic was ready for a genuine constitution to solidify the legal basis of the regime.

The existing Turkish Grand National Assembly was entirely dominated by the newly created Republican People’s Party (known by its Turkish acronym CHP), which had been organized by Mustafa Kemal and consisted of his supporters. In 1924, the National Assembly ratified a new constitution, one that remained in place for almost four decades.

Interestingly, though, the constitution composed by that body contained few hints of Turkey’s emerging one-party authoritarian system, in which the CHP managed virtually all aspects of public life. Instead, the authors of the 1924 constitution gave free rein to philosophical impulses ultimately derived from French political thought. This document’s majoritarian vision of democracy (rooted in the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau) vested most power in the National Assembly rather than the presidency.

This division of powers favoring the Parliament may come as a surprise given President Mustafa Kemal’s paramount position in the new regime, but Turkish constitutionalism had developed during years of struggle against sultanic rule. Despite the authoritarian means used to implement its secularist and modernizing reforms, the early Turkish Republic was careful not to create the impression that a new sultan had come to replace the Ottomans.

Indeed, of all the criticisms directed at Atatürk at home or abroad, one of the most infuriating to him was the accusation that he was Turkey’s dictator. He consciously delegated most executive power to his prime minister, İsmet İnönü, and by the 1930s he often found himself “bored to tears” for lack of work. “In our country,” he wrote to his secretary, “the president’s only function is to sign documents.”

As head of the all-powerful ruling party, Atatürk did have unparalleled latitude to remake Turkey in his own image, but Atatürk’s willingness to abide strictly by the constitutional form of government he had created proved decisive in establishing a stable parliamentary system.

Less than a decade after his death in 1938, Turkey became a genuine multiparty democracy. The first non-CHP government came to power in 1950 with the election of Adnan Menderes from the conservative but also pro-western Democrat Party (DP).

But this did not mean the end of Turkish authoritarianism.

The “Liberal” Constitution of 1960

If a limited presidency had helped prevent the emergence of a dictatorial executive branch, this did not stop the rise of illiberal majoritarianism (i.e., repressive policies practiced by a popularly elected majority government). During a decade in power in the 1950s, Menderes’s Democrat Party unleashed a “white terror” against its opponents, accusing them of communist ties.

|

| Turkish Prime Minister Adnan Menderes |

At the same time, the Turkish military and bureaucratic “deep state” forged by Atatürk and his CHP were not ready to hand power over to Menderes and his fellow upstarts, especially because the DP government had already sent a number of high military officers into retirement.

In 1960, a small group of officers staged a military coup and set the pattern of Turkish politics for years to come. Whenever civilian politicians were perceived as incapable of maintaining stability, the Turkish military stepped in to remake the political and constitutional order.

In the year of direct military rule beginning in May 1960, the leading officers not only practiced political repression (including the execution of Menderes), but also completely rewrote the Turkish constitution.

The constitution of 1961, sometimes known as the “liberal constitution,” was written by an assembly chosen by the military. In reaction to the excesses of the Menderes government (such as the expropriation of CHP assets by the DP government), the independence of institutions such as the judiciary and the universities was guaranteed, and an expanded conception of civil rights was enshrined.

To promote a system of checks and balances, a new constitutional court was established to review the constitutionality of new legislation. The presidential term was extended to seven years, but the presidency was not given much added executive power.

Why did a constitution originating in a military coup have so many liberal features?

A strong majority of the (appointed) assembly in 1961 were members of the politically progressive, but also statist CHP. And the CHP had a close relationship with the Turkish military that allowed them to push forward a progressive constitutional agenda.

Until recently, the perception of CHP links to the military had been played down in public discussions but never fully eliminated. In the eyes of politicians like Erdoğan, the CHP—still Turkey’s second most important party—remains a party of coup plotters (darbecis), aiming to thwart with the will of the people through unelected institutions like the Constitutional Court.

In March of 2014, Erdoğan explicitly compared himself with Menderes: “At that time, they called Menderes a dictator, and now they are calling me one….” Like the DP in the 1950s, recent AKP governments have shown a willingness to move against opposition journalists and officials in the name of the popular will. Clearly, the current Turkish leader acts in the tradition of Turkish democratic majoritarianism represented by Adnan Menderes.

To the dismay of the military, the politicians of the Democrat Party re-emerged in a strong form during the 1960s, even as the political spectrum splintered generally. The military gradually became estranged from all political parties, even the CHP which moved increasingly to the left.

Another military intervention in 1971, albeit not quite a coup, resulted in further constitutional amendments and a purge of progressive military officers. This time, far from solidifying civil rights, the new amendments curtailed constitutional rights.

The political instability of the 1960s was as present in Turkey as elsewhere, and the military saw broad political rights as a cause of this volatility. Yet, despite military intervention, political violence worsened during the 1970s with fighting between left and right on the streets of Istanbul.

The Military Constitution of 1982 and After

In 1980, General Kenan Evren and the military-led National Security Council staged a military coup in order to crack down on political violence and “terror organizations” of the left and right. In the course of the coup, over 43,000 people were arrested.

Yet again, the dual purpose of the coup was both political repression and the remaking of the constitutional order.

A new constituent assembly was chosen by the National Security Council, but this time members of all political parties were excluded. In writing the 1982 constitution, military officers and the bureaucratic elite took the lead in creating a more restrictive constitution, designed to shield the Turkish state from the turbulent democratic politics of the years between 1960 and 1980.

|

| Turkey's 1980 Military Coup |

In this constitution, the emphasis was placed on defining the state’s role and privileges rather than the citizen’s rights. Many articles can be translated with the phrase, “The state shall….” In its initial formulation, the state was referred to as “sublime” (yüce) and “sacred” (kutsal).

Although this language has not survived subsequent amendments since 1982, it is no wonder that the 1982 constitution holds virtually no legitimacy on most of the Turkish political spectrum from the Islamist right to the socialist left, even though it remains in force up to the present day.

This constitution has had particular consequences for the role of presidential authority, because it gave Turkey’s traditionally weak president somewhat expanded powers. As before, the Turkish president was elected by the National Assembly for a seven-year term as head of state while the prime minister served as head of the government. But now the president was granted the power to make a wide range of appointments, including all members of the Constitutional Court and many university administrators. In a crisis, the president was granted the right to rule by decree. In practice, this power has not been used, and Turkey’s parliamentary system has remained intact.

|

| 1980 Coup Leader and Later Turkish President Kenan Evren |

There have been different interpretations concerning the extent of presidential power granted under the 1982 constitution, but given that approval of the constitution was combined with the “election” of Gen. Kenan Evren as president, there seems to have been a link between the new constitution and the office of the presidency.

Evren served as president until 1989 and undeniably put his stamp on Turkey through his control over institutions such as the judiciary and education. (Evren, now 97, was sentenced to life in prison this June for his role in the coup.)

Thus, Erdoğan may be correct when he claims that the current constitution allows for greater presidential power than has been practiced in recent years.

None of the various Turkish constitutions was crafted by a genuinely representative body, and so Turkish parliaments in the past three decades have had the difficult task of re-shaping the democratically illegitimate and statist constitution of 1982 into a broadly acceptable document.

Over time, approximately 70% of the original text has been altered. A major stimulus for these amendments came in the form of European Union accession negotiations, which began to heat up in the late 1990s. Rafts of constitutional amendments were passed in 1999, 2002, and 2004 in order to bring Turkish law in line with European norms.

These amendments were written by, and supported by, a broad spectrum of Turkish political parties, including Erdoğan’s AKP, which was founded in 2001 from among the more moderate remnants of a banned Islamist-leaning party.

Constitutional Reform in the AKP Era

Despite the AKP’s electoral victory in 2002, early AKP governments went to great lengths to preserve multiparty cooperation, especially in matters of constitutional reform. Erdoğan himself had been disqualified from political office due to a previous conviction on politicized charges of “inciting racial or religious strife,” and he was only allowed to run for parliament thanks to CHP support of a special constitutional amendment.

In retrospect, the level of cooperation across the political spectrum that existed at that time was remarkable. A custom had developed that constitutional amendments were usually written by an All-Party Parliamentary Accord Committee in which each party in parliament was represented equally, and this practice was successfully continued under AKP rule, at least initially.

Early goodwill toward Erdoğan and the AKP among anti-statist intellectuals and others began to break down when Erdoğan—himself the former object of a politically motivated prosecution—started to prosecute his own political opponents.

For example, in 2007, Erdoğan seized the newspaper Sabah on a legal technicality and forced its sale. Sabah was then purchased by a company led by Erdoğan’s son-in-law, and it is now seen as a mouthpiece for the government. While Erdoğan is far from the first Turkish politician to engage in this sort of behavior, such actions have fuelled passionate opposition to his government.

Matters came to a head during the so-called Ergenekon trials (2008-2011) in which a number of leading military officers, politicians, and journalists were accused of conspiring against the government. Haunted by a fear of military intervention, Erdoğan’s prosecutors alleged the existence of an authoritarian and ultra-nationalist “deep state” network (known as “Ergenekon”) aiming to overthrow the AKP government.

The opposition argued that these prosecutions were used as a sweeping attack against Erdoğan’s opponents generally, but concerns about possible threats to the AKP government were not wholly unjustified. Even before coming to power, the AKP was menaced with closure by the Constitutional Court for allegedly violating Turkey’s official secularism, and the party narrowly escaped closure again in 2008.

|

| The Controversial “Ergenekon” Trials |

Faced with such threats, the AKP began using constitutional reform to protect itself from entrenched state elites.

In 2007, Abdüllah Gül, the AKP candidate for president, should have won easy election to the presidency based on the AKP’s parliamentary majority, but the opposition boycotted the election, objecting to the idea of a non-secularist president. In particular, Gül’s headscarf-wearing wife caused a stir among Turkish secularists.

As a result, the AKP called for fresh elections and drafted a referendum for a constitutional amendment to create, for the first time, a presidency directly elected by the people of Turkey (rather than by members of the parliament).

In 2010, another referendum passed a new set of constitutional amendments that bundled broadly popular changes with more partisan measures designed to increase AKP influence on the Constitutional Court. Although opposition parties did not support the referendum, the legal threat of closure against the AKP was finally lifted.

The AKP’s internal rules limited AKP deputies (including Erdoğan) to only three terms in parliament, so it is quite possible that Erdoğan had already envisioned himself eventually being elected president by the time of the 2007 referendum in which voters approved direct election of the president.

By bringing the presidency into direct contact with the voters, its character changed from being an instrument of “deep state” tutelage over various institutions (such as the judiciary and the universities) to being a potential expression of the popular will. There is no question that this is how Erdoğan views himself since his election as president in August 2014.

Recent Attempts to Write a New Constitution

In the 2011 parliamentary campaign, the necessity of a wholly new constitution was agreed upon by all four major parties: the AKP, the CHP, the ultra-nationalist MHP, and the mostly Kurdish BDP. Under its new leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP attempted to distance itself from perceptions of closeness to the military and to move toward being seen as a more normal social democratic party .

Both the CHP and AKP called for greater oversight over military affairs, and both envisioned a new constitution enshrining full democratic freedoms, in contrast to the hedging and loopholes found in the current version. The AKP termed such reforms “becoming normal” (normalleşmek), a goal from which the CHP could hardly dissent.

Initially, the constitutional reform process seemed to have great potential. The AKP won the 2011 election handily with nearly 50% of the votes and a large majority in parliament, one of the best results for any party in decades. A “Constitutional Reconciliation Comission” was created with equal representation for the four major parties on the model of previous committees. Substantial progress was made in composing the early articles concerning general civil rights.

However, these elements of apparent ideological consensus did not translate into successful cooperation. There were considerable, possibly unbridgeable differences between certain parties that made consensus unlikely at best. The positions of the ultra-nationalist MHP and the pro-Kurdish BDP are diametrically opposed regarding the issue of Kurdish autonomy, for example.

Much more seriously, AKP proposals for a stronger presidency or even a full presidential system were viewed as unacceptable by the opposition as a whole. The opposition parties knew that a powerful presidency would suit Erdoğan’s personal political ambitions perfectly, and it is largely for this reason that the constitutional reform process slowed to a halt and finally collapsed at the end of 2013.

A two-thirds majority in parliament is needed for any constitutional change, leaving the AKP just short of the ability to amend the constitution unilaterally.

Conceivably, a new constitution granting expansive presidential powers could be passed with the support of the BDP, for example, if sufficient concessions were granted concerning Kurdish autonomy. This strategy, however, could alienate many Turkish nationalist voters in future elections. To be sure, the ultra-nationalists of yesteryear who supported military tutelage over Turkish politics would see an alliance between Islam-oriented and Kurdish political forces as a catastrophe.

In the meantime, Turkish politics has become more polarized than even just a few years ago. Sparked by a conflict over urban space in Istanbul, the youthful Gezi Park protests made headlines throughout the summer of 2013, and Erdoğan’s anger toward opposition activists prompted him to temporarily ban Twitter in early 2014.

The AKP’s rivalry with its fellow religious conservatives in Fethullah Gülen’s Hizmet movement has even led Erdoğan to seek Gülen’s extradition from the United States, so far unsuccessfully. With a new parliamentary election on the horizon, Erdoğan has said that constitutional reform efforts and the enactment of a strong executive presidency will be put off until 2015.

President Erdoğan does face a range of challenges, and the creation of a powerful presidency would be a departure from the Turkish Republic’s historical norms. That said, it would be foolish to imagine that Erdoğan cannot succeed now after so many past victories.

For every Turk who sees him as a would-be dictatorial president, there are others who consider him the representative of the conservative Turkish masses and the fulfillment of democratic majoritarianism.

Cizre, Ümit. Secular and Islamic Politics in Turkey: The Making of the Justice and Development Party. London: Routledge, 2008.

Erdoğan, Mustafa. Turkiye’de Anayasalar ve Siyaset. Ankara: Liberte, 2001. (No relation to the Turkish president.)

Findley, Carter. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Özbudun, Ergun and Gençkaya, Ömer. Democratization and the Politics of Constitution-Making in Turkey. New York: Central European University Press, 2009.

Hale, William and Özbudun, Ergun. Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey: The Case of the AKP. London: Routledge, 2010.

Hamid, Shadi. Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal Democracy in the New Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. (Hamid focuses on election-oriented but illiberal majoritarianism in the Arab world, a concept with some relevance to Turkey as he argues on pages 220-221.)

Kalaycıoğlu, Ersin. “Kulturkampf in Turkey: The Constitutional Referendum of 12 September 2010.” South European Society and Politics 17.1 (2012): 1-22.

Mango, Andrew. Atatürk. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2002.

Özpek, Burak Bilgehan. “Constitution-Making in Turkey After the 2011 Elections.” Turkish Studies 13.2 (2012): 153-167.

Shayambati, Hootan and Kirdiş, Esen. “In Pursuit of “Contemporary Civilization”: Judicial Empowerment in Turkey.” Political Research Quarterly 62.4 (December 2009): 767-780.