Arthur Schlesinger wrote The Imperial Presidency in 1973 in a climate of concern over the unchecked growth of presidential power. While many members of Congress placed restraints on the executive branch, there were conservative politicians who believed that the president had sole control over the foreign policy of the United States.

Indeed, Malcolm Byrnes believes that conflict helps explain the Iran-Contra scandal in part because President Reagan “was viscerally opposed to congressional attempts to limit the ‘imperial presidency’” (xxi). Byrne, who is the Deputy Director for the National Research Archive, challenges the oft-accepted idea that Iran-Contra was a “policy dispute” rather than a criminal act, and that Reagan was unaware of what was going on. Virtually the entire administration, from Vice-President George Bush to Secretary of State George Schultz to Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger knew that their actions were illegal.

When Reagan was elected president in 1980, he and his advisors saw Moscow’s influence on the rise in Latin America, particularly in Nicaragua. However, Congress was not easily swayed to provide aid for the counter-revolutionary Contras. The Boland Amendment was passed to end any overt military U.S. support for the Contras, and by October of 1984 all forms of U.S. support to the Contras had been banned. This did not mean that the Reagan administration ended their support to the Contras, for whom “legal considerations seemed of little interest” (45). The administration then turned to Lt. Col. Oliver North. North is one of the most colorful characters in this narrative: deeply patriotic, fervently dedicated to Reagan, and with a “pronounced tendency to fabricate” (46). North was tasked with building a supply network for the Contras that could operate off the books.

|

| Photo of FDN & ARDE Frente Sur Commandas in the Nueva Guinea zone of Southeast Nicaragua, 1987 |

U.S. relations with Iran were also at a nadir in the mid-1980s. The Reagan administration was desperate for an opening with the Iranian government, yet conventional diplomacy seemed untenable after American hostages were taken in Lebanon in 1984. These kidnappings struck an emotional chord with Reagan, who according to Byrne was determined to return the hostages at any cost (40).

Iran had its own priorities as it fought a grueling war with Iraq even as it was cut off from Western arms manufacturers. Israel emerged as one of Iran’s unlikely allies and sought to sustain its war effort. Here, one of the shadier characters in this sordid drama emerged: Manucher Ghorbanifar, an Iranian arms dealer and former agent of SAVAK, the Shah’s secret police. Ghorbanifar approached the Israeli government in 1985 and claimed to represent a moderate faction of the Iranian government seeking missiles for the war against Iraq. The Israelis then approached the United States to ask for assistance in delivering weapons. National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane approached Reagan about the deal, and Reagan replied that the Iranian “moderates” had to use their influence to return the American hostages.

Ghorbanifar’s story was nonsense. The CIA had previously listed him as an unreliable source, which the Israelis and the NSC decided to ignore. Eventually, even Washington policymakers such as Robert McFarlane acknowledged that Ghorbanifar was an unrepentant liar, though only after the scandal had been fully played out.

These two disparate incidents were joined together when Oliver North suggested to the National Security Council that future arms deals happen directly through the United States and that a portion of the proceeds be used to fund the Contras. Though virtually all of this activity was illegal, the proposal received Reagan’s approval. Administration officials focused on how to conceal the operation and protect themselves and the administration if events came to light (83).

All of this came tumbling down when a Nicaraguan soldier shot down a Contra resupply plane in October of 1986. The pilot admitted to be in the employ of the CIA. One month later, a Lebanese magazine published allegations about the arms-for-hostages deal, which the Iranian government confirmed. After North and other actors did their best to destroy documentary evidence that could have implicated Reagan, there followed the Tower Commission, a congressional inquiry, and the Office of the Independent Counsel. The Independent Counsel’s convictions of administration officials were overturned by presidential pardon or by appellate courts.

|

| From left to right: Caspar Weinberger, George Schultz, Edwin Meese, Don Regan, and President Ronald Reagan read notes before telecast regarding arm sales to Iran on November 25, 1986. |

Byrnes concludes by noting continuities between the Reagan administration and the second Bush administration. Dick Cheney figures into the background of this story as one of Reagan’s few strong supporters on Capitol Hill. Cheney was part of a minority of Republican congressmen who dissented with the congressional inquiry. In a written minority opinion, he and others opined that the Iran-Contra dealings had been legal. Rather than limiting executive powers, the dissenters instead believed that congressional oversight over the executive needed to be lessened. This report continued to play a role in Cheney’s thinking, as Byrne writes that “In later years, Cheney, while serving as vice president in the George W. Bush administration, cited the report as a blueprint for his thinking on presidential power” (304).

The play-by-play description of the arms deals and North’s dealings with the Contras are livened up by the absurdities of the affair. In one telling, when Robert McFarlane went to Tehran in the hopes of negotiating with the Iranian “moderates” (who themselves had been duped about McFarlane’s intentions), he brought a cake in the shape of a key. He hoped that the gift would help “unlock” U.S.-Iranian relations (195). Unsurprisingly, the gesture was lost on the baffled Iranian delegation. In another example, Reagan failed to read important briefings for the Williamsburg economic summit and instead stayed home to watch The Sound of Music. Without these moments, the minutiae presented here can feel overwhelming to a general reader.

|

|

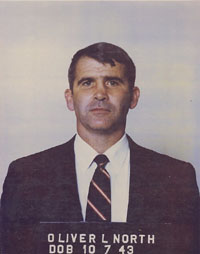

| Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North's (of the National Security Council) Mugshot, following his arrest |

One of the implicit questions in this book is why Iran-Contra didn’t generate the anger that the Watergate Scandal had. Byrne addresses a number of reasons why the events diverged: “Reagan was much more popular personally than Nixon, the political landscape had changed substantially as a result of declining economic conditions…and Congress had largely shed its reformist posture of the 1970s” (279). Byrne’s account would be fuller if the failure of Senate Democrats factored into the narrative more strongly.

Deception is one of the powerful themes of this book. Virtually all of the major actors lie or distort the truth as it suited their needs. The NSC put up with Oliver North’s lies and fabrications, Ghorbanifar lied to the Americans and Iranians, and Reagan was at the very least disingenuous about trading arms for hostages. People didn’t just lie to each other, for that matter, but they lied to themselves as well. It turns out that hearing only what you want to hear is dangerous in foreign policy.

Byrne’s book is all the more instructive if one keeps in mind the foreign policy of the last two presidential administrations. The power of the president to conduct foreign policy without oversight has become the norm in the United States. The imperial presidency was in place long before Reagan, but its current proponents all got their start dealing with Iran-Contra.