The movement for LGBTQ rights began in cities. But in recent years, it has moved to the suburbs as well, creating some strange political bedfellows in the process. This month, historian Clayton Howard focuses on developments in Ohio to show how in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, some urban planners saw the "creative classes" and gay friendly districts as engines of economic development. LGBTQ activists have found themselves working with those more concerned about business than civil rights and these partnerships have, in some cases, solidified other forms of discrimination and exclusion in suburban areas.

In November 2018, approximately a hundred people gathered in Medina, Ohio’s city hall to debate two proposed laws that would have prohibited discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations based on a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

Crowd gathers to witness the passage of new laws banning discrimination based on a person's sexual orientation or gender identity in Medina, OH, 2019. Photo courtesy of OutSupport.

For almost two hours, the bills’ supporters testified in personal terms about the need for such protective legislation in the Akron suburb. Transgender and queer young people spoke about harassment at school and work. A woman told the audience that even though she had married her wife in 2015, she still worried that they could face legally permitted discrimination in a local restaurant.

Parents shared their hopes that a new law would make their families feel safe and accepted. Eric Varndell said he hoped that his transgender son and bisexual daughter might someday choose to move back to Medina to “live and contribute to the community” without fear of persecution “simply because they are fully expressing who they are.”

Until 2020, no federal law forbade discrimination based on a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. Last June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in several cases that employers who fired gay or transgender workers violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

These landmark decisions represent an important milestone for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) equality, but they leave important questions about access to housing, education, and public bathrooms unaddressed. Furthermore, they permit certain exemptions based on religious grounds, allowing some employers to discriminate based on their faith.

High school students share letters of support for LGBTQ protections in Medina, 2019. Photo courtesy of OutSupport.

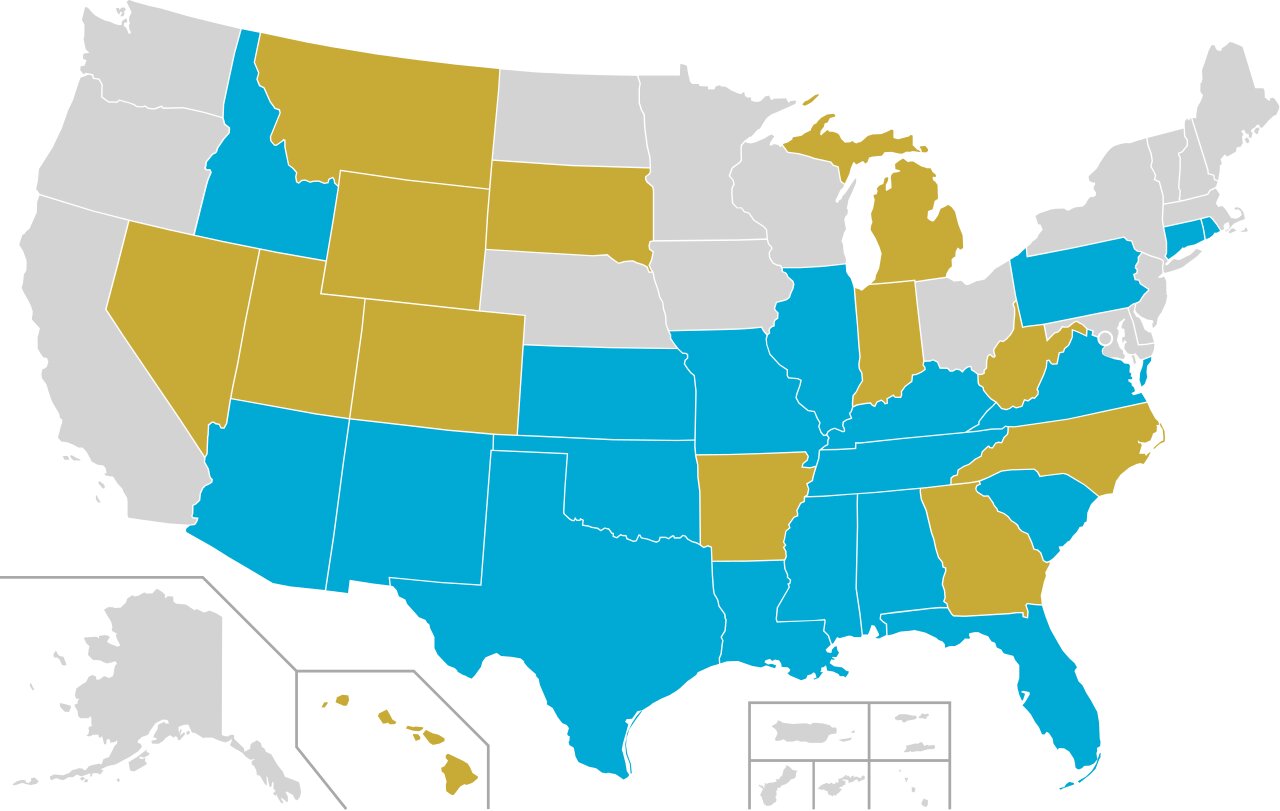

Today, Ohio is one of 29 states that lack statewide protections based on a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. A 2020 report by the Movement Advancement Project (MAP) found that roughly half of all LGBTQ people in the United States lived in places with explicitly homophobic and transphobic legislation or in places with no explicit legal protections.

Organizers in Ohio and other states have tried to fill the gaps at the federal and state levels with local laws, like the bills introduced in Medina. Since 2015, 16 cities, villages, or counties in Ohio have passed or strengthened nondiscrimination ordinances, and proponents of LGBTQ equality have won similar victories in nearby Indiana, Michigan, and Kentucky.

These campaigns have sometimes faced stiff resistance. Opponents of the laws in Medina, for example, tried and failed to repeal them in 2019 and 2020. Yet these new laws are also evidence that rising national approval of same-sex marriage is translating into meaningful support for LGBTQ equality at the local level.

Nevi Kotzevi, center left, and Maggie Best-Miller, center right, hold bouquets as they are married by Mayor John Cranley before a throng of supporters and journalists at Fountain Square in Cincinnati in 2015 after the Supreme Court declared that same-sex couples have a right to marry anywhere in the United States. AP Photo, John Minchillo. Used with permission.

National surveys have found that a vast majority of Americans approve laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and their support grew even stronger after the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage across the country.

While these laws promise to make the lives of LGBTQ fairer and safer, many local officials have supported them for reasons that sometimes have surprisingly little to do with the welfare of actual LGBTQ people. The communities passing these laws vary in size, wealth, and racial composition, but proponents of nondiscrimination laws have used a remarkably similar language to justify their cause in almost all of them: economic development.

When Medina City Council President John Coyne spoke out in favor of the nondiscrimination ordinances in 2018, for example, he privileged the well-being of the wider suburb and economic development. “I don’t think that we as representatives of the community want to promote anything that could perpetuate hate,” he said. “We want people to come to Medina and say, ‘That’s a great community and I want to live there.’”

If anyone failed to understand Coyne’s words, City Councilman Dennie Simpson made the subtext of his comments explicit a few minutes later by joking, “What John failed to mention is that he wants everybody to spend their money in Medina!”

The downtown square of the City of Medina in Ohio, 2007.

Hate, in other words, hurt development.

For much of the twentieth century, political and economic leaders in the United States largely saw LGBTQ people as signs of economic decline. Beginning in the 1990s and early 2000s, however, a group of innovative urban planners tried to convince local authorities in Ohio and other places that LGBTQ people were good for business.

Consequently, LGBTQ activists in the past 30 years have sometimes found powerful allies in local chambers of commerce and city councils in places like Medina, regardless of whether these municipal leaders sympathized with the larger gay or transgender rights movement.

Yet these elites have also narrowed the debates around equality in two important ways. First, they have often favored laws with weak enforcement provisions. In some cases, they have seen the new laws as mere signals of progressive politics in an otherwise exclusive, often racially segregated, community, rather than as meaningful safeguards for LGBTQ people.

Second, local officials and business leaders have supported new protections primarily because they have wanted to generate commerce or raise property values. In some case, they have seen LGBTQ rights as a strategy to gentrify poor neighborhoods.

Carla Hale delivering a statement confirming her firing from Bishop Watterson High School during a press conference in Columbus, Ohio in 2013. Hale was fired from Bishop Watterson H.S. for being in a gay relationship. Although many cities like Columbus have nondiscrimination ordinances, they do not always apply to religious organizations. AP Photo/ Columbus Dispatch, Adam Cairns. Used with permission.

Neither leading nor lagging, Ohio offers an important case study to understand these trends. In the heart of the Rust Belt, many of the state’s metropolitan regions suffered acute job losses and declining tax bases in the late 20th century. These crises, therefore, made many Ohio officials particularly eager to link nondiscrimination laws with economic development.

Heterosexuality, Race, and the Postwar Suburbs

In some respects, it might seem surprising that anyone would see LGBTQ protections as a good economic development strategy. Businesses, banks, and governments have often determined a place’s value based on the kinds of people who lived or shopped there, and for most of the 20th century officials in Ohio and other places specifically saw LGBTQ people as threats to investment.

After World War II, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Administration (VA) made it easier for more Americans to buy homes, and they encouraged banks to lend more by insuring their losses.

However, this subsidy for homeowners came with restrictions. The federal government forced banks to follow rules, including forbidding them from lending to borrowers that officials deemed too risky. These requirements included preferential treatment for married men, excluding almost all nonwhite borrowers, disqualifying applicants that banks deemed immoral, and rejecting borrowers who planned to live with people outside of marriage.

Winkelman's Department Store in the Parmatown Shopping Center in Parma, OH, 1960. Photo courtesy of Special Collections, Cleveland State University Library.

These federal policies, combined with actions by local governments and private businesses, fueled suburban growth after World War II. They also ensured that many new communities would be almost exclusively white with large percentages of married couples.

Many corporations and department stores saw these segregated, normative communities as ideal places to relocate, and suburban governments tried to attract new tax bases by marketing themselves as “family friendly.”

These attempts to lure outside capital also meant that newer communities often excluded public housing, bars, or developments that might hurt their reputations as good places for white people to marry and raise children.

Federal and business preferences for the suburbs, in turn, dramatically reshaped urban centers.

Excluded from most new developments, growing numbers of LGBTQ people of all races lived openly near older downtowns. During the 1950s and 1960s, queer bars, bookstores, and in some cases, local chapters of the Mattachine Society—one of the first gay rights groups in the country—opened in urban centers.

Gil Thurman of Dayton vice squad poses with magazines in 1967. During the 1950s and 1960s, most cities in the U.S. had police units dedicated to closing adult bookstores and gay bars. Courtesy of Wright State University Libraries' Special Collections & Archives.

By the 1970s, like other parts of the country, cities such as Cleveland and Cincinnati boasted LGBTQ-friendly churches, businesses, and community groups. Although some LGBTQ people resided in rural places or newer suburbs during this era, the prejudices of federal authorities and suburban developers inadvertently made cities easier places for them to live openly.

Many urban officials and economic elites interpreted the outward migration of businesses to the suburbs and the influx of residents of color and LGBTQ people as a crisis. Cities’ declining tax bases were real problems, but elected officials and downtown business interests often shared the homophobic and racist assumptions of their suburban counterparts.

Young African Americans congregating on street corners, pornography stores, sex workers on sidewalks, and gay bars frequently looked like “blight” to them. These concerns provided context for rising homophobia in older cities.

In 1965, a Dayton, Ohio newspaper warned that the city had developed a reputation as a “Gay Town” and that downtown elites wanted a crackdown on LGBTQ people: “‘We try to keep them out of here,’ one businessman said. ‘They’re a nuisance … And they keep the other customers away, because single men and women who are normal aren’t going to patronize a place known as a hangout for a gay crowd.’”

Consequently, city leaders tried to remake downtowns into places that might appeal to white, straight-presenting residents and consumers. As in other states, every Ohio city policed public areas where LGBTQ people congregated. Cincinnati authorities passed a law restricting gender transgressive clothing in 1964 because they worried about “gay people” who were “gathering downtown.”

The Fez bar in downtown Akron, OH, 1971. The police frequently raided the bar because they believed that the clientele was bad for other businesses. Photo courtesy of Akron Beacon Journal- USA Today Network.

These attempts to police LGBTQ spaces paralleled and reinforced plans to raise property values in central business districts and to displace African American residents. In 1970, police harassed patrons at the Fez bar in Akron because they believed it catered to “prostitutes, pimps, homosexuals, and transvestites.”

The bar was in a census tract that was 17 percent Black, and it was next to another tract which was 85 percent Black. When the owner complained about their harassment, the Akron police responded by explaining that they were specifically interested in helping to redevelop the city’s downtown, “Here we’re trying to interest people in [urban] renewal, trying to interest investors…what we are concerned about is letting an area go to hell.”

These conflicts ultimately caused political organizing in LGBTQ communities. During the 1960s and 1970s, organizations primarily based in cities across the country fought police harassment, employment discrimination, and other forms of persecution directed at LGBTQ people.

A speaker supports a bill for a homosexual rights ordinance in Columbus, Ohio in 1984. Columbus Citizen Journal Collection. Scripps-Howard newspapers/ Grandview Heights Public Library/ Photohio.org

In 1978, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that police harassment had driven lesbians and gay men in the city to organize politically. “The most frequently expressed goals of the group,” the newspaper reported, “were ‘to get the police off our backs’… and to push for [the] adoption of a proposed human rights ordinance, which would protect homosexuals, among others, from discrimination.”

The Sexual Revolution, Cities, and the Creative Class

This activism unfolded amid a wider transformation in American cities and a shift in how elites understood urban economies. During the 1970s and 1980s, many Americans delayed marriage and had fewer children. Numerous middle-class Americans, in particular, celebrated a phase of their lives before marriage when they dated and had sex.

For older cities, this dimension of the sexual revolution offered an economic opportunity. Young, frequently white, professionals settled in urban neighborhoods, renovating older buildings near downtown.

The Crazy Ladies Bookstore, a lesbian-owned business in Cincinnati's Northside neighborhood in the 1990s. Photo courtesy of Ohio Lesbian Archives

Some of these new gentrifiers were relatively affluent gay men and lesbians, but most were straight-identified people with few or no children who frequently saw the suburbs as too boring or homogenous. Older cities gradually sought to attract these residents, rezoning neighborhoods to allow for new bars and restaurants. Cities like Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus encouraged historic preservation and offered tax breaks to businesses catering to young unmarried people.

The sexual revolution’s effect on urban property values greatly accelerated after economists and planners began to celebrate the business potential of what they called the “creative class.” Beginning in the 1990s and early 2000s, numerous writers argued that the most talented workers and cutting-edge capitalists wanted to live in diverse, exciting places.

These urban planners explained that software coders, bioengineers, and the firms that employed them had the privilege of choosing where they wanted to settle. Cities, therefore, needed to make themselves attractive to these skilled “creative” workers.

Crucially, they argued that urban centers needed to avoid the stigma of closed-mindedness since the leaders of the new economy allegedly valued diversity. A journalist for Governing magazine summed up the new logic when he explained, “[O]ne of the things that the creative class looks for in a place to live … is tolerance, not just towards gays but toward people with purple hair, wear nose rings, or culturally distinctive in almost any way.”

Best-selling author and urban planner Richard Florida visits an art and design studio in Dayton, OH in 2008. Photo courtesy of Southwestern Ohio Council for Higher Education.

No person in this era celebrated the virtues of diversity and the creative class more than urban planner Richard Florida. Comparing urban regions in the 1990s, Florida concluded that all of the economic success stories of the decade shared, among other things, a welcoming atmosphere for gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, transgender, and queer people.

Relying on a “tolerance index,” he concluded that the areas with the most inclusive policies for gay people also had the most dynamic economies. “Diversity is not just an ethical imperative,” Florida argued. “It is an economic driver… LGBTQ inclusion draws top talent in industry, art, and education, and, in turn, attracts business.”

Florida, however, delivered bad news to many of Ohio’s biggest cities. Cleveland ranked just 43 out of 50 on his ranking of gay-friendly cities in 2001. He told a meeting of downtown elites that the most talented workers already know “what Cleveland has to offer,” and they had decided, “‘That’s not for me. I’m going to Austin.’”

The Cincinnati City Hall as it appears today.

When Florida visited Cincinnati in 2002, he mocked the city for the fact that it had amended its city charter to prohibit any future LGBTQ protections in 1993: “You guys slack off real bad on the gay index,” he said, “You’ve got to work on the diversity piece. You have to have an environment where new people are almost immediately grabbed and accepted.”

Florida did not exactly consider himself an activist for LGBTQ equality. He was most interested in solving cities’ fiscal problems, and some scholars disagreed with his theories. Nevertheless, Florida and his supporters helped convince many powerful people that diversity was in their self-interest.

In the early 21st century, several Ohio cities passed legal protections for LGBTQ people, and proponents of the laws frequently referenced his work or related arguments about economic development. When Cincinnati passed a nondiscrimination ordinance in 2006, City Councilman Chris Bortz, a real estate lawyer, argued: “Cincinnati must be viewed as a place that welcomes diversity. That’s what makes us attractive to the creative class.”

Cincinnati Mayor Charlie Luker calls on voters to repeal a 1993 city charter amendment that made Cincinnati the only U.S. city to ban enactment or enforcement of laws based on sexual orientation. By the early 2000s, many mayors believed that LGBTQ protections helped economic development. AP Photo, Al Behrman. Used with permission.

A year later, when Dayton passed its own LGBTQ protections, the city’s largest newspaper editorialized in favor of the bill by referencing Florida’s ideas: “[Dayton] is losing population and has a problem attracting middle-class people with children. Other cities have done well attracting gays, many of whom have disposable income and other assets the community needs.”

As evidenced by the Dayton editorial, Florida’s Ohio adherents often conflated “gay” with “affluent.” These ordinances frequently protected people based on their gender identity as well as their sexual orientation, but elite advocates for these laws rarely mentioned lesbians or transgender people, much less the nation’s high rates of LGBTQ teen homelessness.

Instead, they often linked gay men positively with gentrification. This involved a certain degree of stereotyping, but it also frequently pitted equality for relatively affluent gay people against the rights of poor people of all sexualities and gender identities.

Starting in the 2000s, business leaders in Ohio and other places frequently sought to use LGBTQ rights to help gentrify downtowns. Don Iannone, director of economic development at Cleveland State University, for example, made the perceived boons of this strategy explicit: “The gay community is a very wealthy community, as a rule. It’s been a very powerful force in inner-city revitalization in many, many cities.”

Storefronts on Hamilton Avenue in Cincinnati's Northside neighborhood in the 2000s. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, some urban planners saw gay-friendly districts like this one as engines of economic development. Photo by Jerome Strauss.

More importantly, the same people who tied these protections to economic development sometimes distanced themselves from the rights of LGBTQ people altogether. Or as an opinion writer in the Cincinnati Enquirer put it, nondiscrimination laws were “Good for Straight People, Too.”

To be clear, LGBTQ people often led the campaigns for these ordinances, which sometimes provided tangible benefits to victims of discrimination. Yet the logic of economic development often forced LGBTQ activists into alliances with straight-identified, cisgender people who sometimes minimized their cause.

Rod Frantz, president of the Richard Florida Creative Group, reassured potentially homophobic business leaders in 2003 by saying, “Richard is heterosexual. I’m married and heterosexual. We’re not advocating for more homosexuality. But all of the exit polls we’ve done with creative class people … show that they look for diversity, and that includes diversity in sexual preference.”

Having powerful allies clearly made the fight for LGBTQ protections in Ohio and other states easier, but arguments about economic development often reflected influential elites’ weak commitments to equality.

The Procter and Gamble Headquarters located in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio.

In 2004, for instance, a group of lesbian, gay, and bisexual workers and their allies helped convince Procter and Gamble, Cincinnati’s largest corporate employer, to support a citywide nondiscrimination ordinance. At the same time, however, the company refused to support legalizing same-sex marriage.

Furthermore, elite-led development strategies often placed relatively affluent white gay men and lesbians in conflict with low-income communities of color.

In 2003, Laura Poitras and Linda Goode Bryant chronicled fights over gentrification in Columbus’s Old Towne East neighborhood. In their documentary film Flag Wars, the filmmakers depicted white lesbians and gay men renovating old houses and displacing longtime African American residents in the area. While the film shows that both communities faced discrimination, it also highlights the ways that city officials clearly favored white gay gentrifiers over their poorer Black neighbors.

Legal Protections and Suburban Competition

Many Americans today to associate vibrant LGBTQ life with urban centers. Yet since the 1970s, more and more gay and transgender people have lived openly outside of cities. In Ohio and other states, many legal battles around queer parenting or LGBTQ children have taken place in suburbs and often have made the suburbs more “gay family friendly.”

Summit County Gay Coalition rally in Barberton, OH, a suburb of Akron. During the 1970s and 1980s, many suburban LGBTQ people in the U.S. fought many forms of discrimination, including issues related to parenting. Photo courtesy of Akron Beacon Journal- USA Today Network.

After leaving straight marriages or while pursuing an adoption, many gay suburbanites fought difficult custody battles for their kids. Just as importantly, cisgender and straight-identified parents of LGBTQ kids have also played pivotal roles in changing the policies of suburban school districts.

Groups like Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) have mobilized suburbanites around issues like bullying and harassment in K-12 schools. In 1995, Karen and Robert Gross founded the group TransFamily in the Cleveland suburb of Lyndhurst. This organization has offered counseling and support groups for transgender youths and their families and has advocated for transgender-friendly policies at the state and local level.

Recently, many of these LGBTQ suburbanites and their families have played important roles in promoting new nondiscrimination laws. Gwen Stembridge, anorganizer for Equality Ohio, recalled that OutSupport, a group for LGBTQ people and their families, played an important role in convincing public officials to pass the ordinance in Medina.

Pride Flyer from TransFamily in 1997. Image courtesy of The Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, OH.

In some cases, state organizers have worked with LGBTQ people in local positions of authority. When Ron Hirth, for example, was elected mayor of the Village of Golf Manor, he became the first openly gay mayor in southwest Ohio. Hirth, other village leaders, Equality Ohio, and the Human Rights Campaign worked together for two years to pass the Cincinnati suburb’s nondiscrimination law in January 2020.

Just as cities have seen “diversity” as a necessity for attracting talented workforces and businesses, many suburbs have passed nondiscrimination ordinances partly in the name of economic development.

Like cities before them, some older suburbs have struggled with declining tax bases and rising poverty rates. But unlike urban centers, these suburbs have had fewer resources to confront the problems. Approximately 20 percent of Golf Manor residents currently live below the poverty line, for example, and the village adopted its LGBTQ rights ordinance as a part of a larger plan to attract new residents and businesses.

Even older, relatively affluent communities have added LGBTQ protections due to metropolitan competition. Bexley, Worthington, and Westerville near Columbus all adopted nondiscrimination ordinances, in part to attract young professionals.

The LGBTQ-friendly laws were a part of larger campaigns to market these wealthy suburbs as places with walkable downtowns, bike paths, and more progressive attitudes than conservative suburbs farther away from the central city.

Unfortunately, like many city elites, numerous straight-identified, cisgender suburban policymakers have also often had an uneven commitment to LGBTQ rights.

In 2015, LGBTQ groups across the country boycotted companies in Indiana after the state passed a law allowing businesses great latitude in defining how their religious beliefs would affect their treatment of gay or transgender customers and employees.

Gwen Stembridge found that these boycotts motivated some suburban policymakers in Ohio to pass new protections, but they sometimes worried more about eliminating the appearance of discrimination than actually ending it.

In 2018, even as Golf Manor authorities drafted their nondiscrimination ordinance, the village revised its rules governing the status of people convicted of sex offenses. That year, two landlords who had contracted with a local agency to house “homeless sex offenders” alleged that the village had re-designated a tiny patch of land near their property as a “park,” thus forcing their tenants to move or break the law.

And when Medina debated its nondiscrimination ordinance in 2018, all the witnesses who testified for the bill highlighted the suburb’s many virtues, except for Lauren Green-Hull, the associate director of a local fair housing agency. Instead, Green-Hull argued that Medina needed the law because its residents and businesses were already discriminating.

She testified that in the previous three years her agency had received seventy-five calls from “people who worried about discrimination” in Medina and that 34 other people had told state officials that they had experienced racial, religious, or gender discrimination in the suburb.

Towards Metropolitan Equity

In many ways, the passage of LGBTQ-friendly ordinances represents a much-needed change from the discriminatory laws of the mid- to late twentieth century. For many LGBTQ people in Ohio and other states, they offer important shields against personal prejudice and institutional discrimination.

More importantly, advocates for these laws argue that each city or county ordinance might inspire other places to adopt similar legislation, producing a “snowball effect” for LGBTQ equality up to the state legislature. As Gwen Stembridge from Equality Ohio rhetorically asked, “Who wants to be the last suburb to add a nondiscrimination law?”

Black Lives Matter demonstration against white supremacy in Medina, OH, 2020. Photo courtesy of Tina Forhan.

But LGBTQ protections can coexist with or reinforce other kinds of oppression. Some public officials have pursued a “rainbow washing” strategy that promotes tolerance for some, frames LGBTQ people primarily as wealthy consumers, and helps mask other kinds of discrimination.

This history, furthermore, reveals the ways that these nondiscrimination laws can make elite suburbs seem even more exclusive specifically because they are more tolerant of gay and transgender residents. Officials in places like Medina or Westerville can promote an “inclusive exclusivity” where the creation of an LGBTQ-friendly law allows them to market themselves as more enlightened than other suburbs and avoid confronting their own patterns of discrimination.

The fact that many straight-identified, cisgender elites have seen nondiscrimination ordinances as good for business has given LGBTQ people important allies in the struggle against transphobia and heterosexism. But it has also made it harder to create laws with strong enforcement mechanisms and has sometimes pitted marginalized communities against one another.

Strong state or federal legislation could safeguard LGBTQ workers, residents, and consumers, while also eliminating the municipal competition that promotes ineffective laws and rainbow washing. Yet policymakers who truly believe in equality will also need to pair nondiscrimination ordinances based on sexual orientation and gender identity with reforms that cut across metropolitan regions.

A Black Lives Matter rally in Medina in 2020. Recently, some white suburbanites in the U.S. have tried to reckon with the history of exclusion in their communities. Photo courtesy of Tina Forhan.

The same competition that incentivizes local governments to protect people based on their sexual orientation or gender identity also encourages them to exclude others that they believe will hurt investment. State and federal authorities, therefore, will need to think expansively about the intersections among local police, zoning boards, schools, and other institutions that encourage exclusion in the name of economic development.

Thank you to Rin Reczek, Alison Lefkovitz, and Tim Retzloff for their help with this essay.

Laura Durso, et al. “Advancing LGBTQ Equality Through Local Executive Action,” Center for

American Progress, 25 August 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/reports/2017/08/25/437280/advancing-lgbtq-equality-local-executive-action/

Lilian Faderman, The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (2015)

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life (2002).

Suleiman Osman, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for

Authenticity in Postwar New York (2011).

Timothy Retzloff, “The Association of (Gay) Suburban People: Gay Activism, and the Occasional

Tupperware Party in an Era of Entrenched Homophobia,” Places (2015).

Daniel Winunwe Rivers, Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and Their Children Since World War II (2013).

Timothy Stewart-Winter, Queer Clout: Chicago and the Rise of Gay Politics (2016).

Susan Stryker, Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (2017).

Films and Multimedia:

Cincinnati Goddamn (2013)

Flag Wars (2003)

Ohio Lesbian Archives, blog, https://ohiolesbianarchives.wordpress.com

Sexing History, podcast, “Prom Night” (2018)