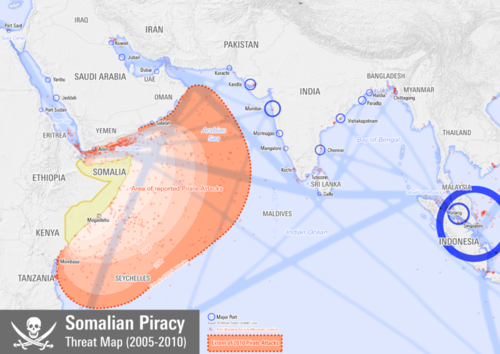

In 2009, according to the International Maritime Commission, the waters off the northeastern coast of Somalia had more acts of piracy than anywhere in the world. The film Captain Phillips (2013), directed by Paul Greengrass and based upon the 2011 memoir by Richard Phillips, tells the story of one of the most sensational events of 2009—the hijacking of an American cargo ship and the dramatic rescue of its heroic captain.

The larger issues of global class and economic differences are set in the first few minutes. The American, Captain Phillips (Tom Hanks), is introduced in his study in a white frame house in Underhill, Vermont, preparing for his trip navigating the Maersk Alabama from the Port of Salahah in Oman to Mombasa, Kenya. Driving in a late-model Toyota van to the airport, Phillips and his wife express concern that their children are just not tough or disciplined enough to survive in the new world of global competition. Phillips aims to deliver his cargo as expeditiously as possible so that he can return to his comfortable home and family.

The pirate Captain Mare (played by Barkhad Abdi, a Somali refugee living in Minnesota) is introduced sleeping on the floor in a cinder-block bunker in Eyl, a shanty-town on the Indian Ocean. Summoned by businessmen who arrive in SUVs to demand that he get back out to sea to make more money, Mare recruits a crew from a crowd of hungry, muscular, young men struggling to survive in one of the least stable states in the world. Mare would like another big reward, similar to a $6 million dollar reward collected in ransom for a Greek ship, so that he can one day travel to America and buy his own car.

The dramatic, action-filled hijacking reveals the peculiarities of international maritime and insurance law. For two anxious days the Maersk Alabama, defended only by fire hoses and flares, is stalked by the four khat-intoxicated, armed men in an open skiff. Professional and self-righteous, his ship loaded with food aid for hungry Africans, Phillips instructs his 20-man crew that if boarded by pirates, their orders are to lock themselves in the engine room.

The tense, threat-filled dialogues between the Phillips and Mare reflect their different positions in the global capitalist order. The American captain argues that he is in international waters, and he questions Mare’s claim to be a fisherman. He also advises Mare that the 30,000 U.S. dollars in the ship safe is a decent reward. Mare responds that international ships do not respect Somali waters—providing a nationalist rationale for his actions—and that he needs 10 million dollars for his bosses. For Mare piracy is not terrorism, just a business transaction between the rich and poor.

Not surprisingly, the citizens of the rich and developed world win out. Within thirty-six hours Captain Phillips and the Maersk Alabama are rescued by three United States Navy ships, armed with drones, helicopters, night-vision telescopes, and Navy Seals who parachute onto the scene after an emergency flight from Virginia. The Somali pirates have only their machine guns and a mother ship with engine trouble. Mare does get to travel to America, but as a prisoner.

The author, Andrew Carlson, is also the author of two Origins articles:

“The Pirates of Puntland, Somalia”

“Who Owns the Nile? Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia’s History-Changing Dam”