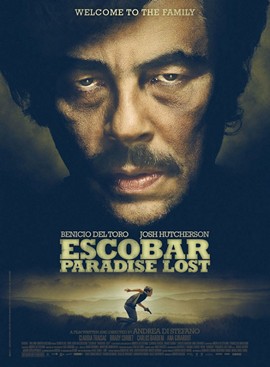

Escobar: Paradise Lost is the directorial debut of Andrea Di Stefano, who also wrote the film. Set in Colombia in the 1980s, the movie follows the romance of Canadian surfer Nick (Josh Hutcherson of The Hunger Games fame) and Maria (played by Spanish television star Claudia Traisac). As part of their courtship, Maria introduces Nick to her family, including her uncle, the drug lord Pablo Escobar (played by Benicio Del Toro).

|

| Escobar: Paradise Lost, directed by Andrea Di Stefano |

Del Toro is not the lead, and this is unfortunate because he steals the film from the very first scene. In fact, Del Toro’s performance here feels like an encore of his role Steven Soderbergh’s 2008 epic, Che, in which he plays the title revolutionary. That movie feasted on Del Toro’s intensity and calculated facial expressions of the sort we see here.

Hutcherson’s role as the main character, by contrast, feels like the product of lazy casting. Indeed, while the chemistry between Nick and Maria looks great on film (Hutcherson and Traisac are rumored to be dating in real life and Traisac plays her part well, fully utilizing her skills from television work to convey sensuality, fear, and the poise of a young woman both proud and aware of her uncle’s profession), Hutcherson’s scenes with Del Toro and other actors might have been just as convincingly played by any number of Hollywood’s rising twenty-something male leads.

Escobar ’s plot is rather formulaic: Nick enters the world of Colombian drug trafficking, gains the trust of the kingpin, and must choose whether being a part of that world is worth sacrificing his humanity. Asked to hide a portion of Escobar’s wealth, the drug lord orders Nick to execute a Colombian guide. Unable to cross that line, Nick and Maria decided they must flee from Escobar’s soldiers.

| Entrance to Hacienda Napoles, the main Escobar compound, with a gate adorned with Escobar's first smuggling plane |

Born in 1949, Pablo Escobar rose to power as a petty thief who turned to kidnapping and smuggling by the early 1970s. With the purchase of a small fleet of airplanes, Escobar began to move cocaine from Colombia to the United States via Panama. By the early 1980s, Escobar was a millionaire, the head of the powerful Medellín Cartel, and the largest supplier of cocaine to the United States. Through his money and influence, Escobar gained power as an elected official in Medellín while simultaneously eliminating political rivals and government opponents.

|

| Pablo Escobar's death, as portrayed by artist Fernando Botero |

Escobar and his family always presented theirs as a Robin Hood operation that gave back to the Colombian workers and residents in the countryside, and the film shows the popular support Escobar had with the working community. Escobar did indeed donate millions to the Catholic Church, build homes, soccer fields, and invest in the state’s infrastructure. One of his homes even had a zoo open to locals, keeping Escobar within the good graces of the community.

At the same time, as James Mollison’s documentary collection The Memory of Pablo Escobar, demonstrates Escobar’s brutality against his enemies or those he perceived as enemies, helped expose his operation to authorities. These activities met with significant resistance from the Reagan Administration, as the United States initiated anti-drug operations within United States and helped fund anti-Escobar operations in other parts of the Americas.

And as Robin Kirk points out in the book More Terrible than Death: Massacres, Drugs, and America’s War in Colombia, whatever goodwill Escobar displayed, government authorities from both Colombia and the United States were quick to use television and radio broadcasts to point out his tactics of assassination, employing child soldiers, and bankrolling local officials.

|

| Painted Portrait of Pablo Escobar |

The film shows both sides of Escobar: the compassionate, family-oriented politician and businessman who transforms into the cold, ruthless drug lord and they are brought together in a climactic moment. Nick, unable to kill his guide, finds that Escobar planned to kill him whether Nick completed his task or not. Nick calls Escobar to demand an explanation for Escobar’s betrayal. Escobar, who had been reading to his children from The Jungle Book when Nick calls, answers that, like the hero Mowgli, one must sometimes leave one’s animal friends behind in the jungle. It is perhaps the most chilling scene Del Toro delivers in the movie.

By focusing on the family drama, the film only hints at Escobar’s network of informants, dealers, smugglers, assassins, and accountants, and various other operatives do not get the attention they deserve here. These were the people who kept Escobar rich and alive. Likewise, the political problems of Colombia in the 1980s are barely mentioned. Escobar’s brother, Roberto, notes in The Accountant’s Story: Inside the Violent World of the Medellín Cartel that the violent conflicts between conservatives and liberals in Colombia allowed non-government entities, such as the drug lords like Pablo Escobar, to provide basic social services, employment, and benefits to those whom the government ignored.

Escobar: Paradise Lost is a well-produced depiction of Escobar during the final years of his criminal empire, but this story is placed within an unfortunately average romantic-action movie with awkward editing. Perhaps Hollywood’s next Escobar project, El Patron, John Leguizamo’s 2016 biopic of the drug lord, will be better.